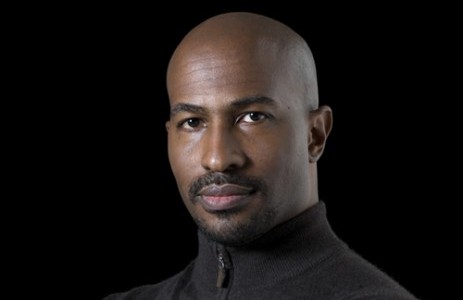

Van JonesBy now the Strange Episode of Van Jones is well known in and outside of politics. Jones became White House Special Advisor for Green Jobs in March of 2009. Shortly thereafter began a summer of crazy, as Tea Party activists stormed congressional offices and the air waves, shouting warnings of incipient tyranny.

Van JonesBy now the Strange Episode of Van Jones is well known in and outside of politics. Jones became White House Special Advisor for Green Jobs in March of 2009. Shortly thereafter began a summer of crazy, as Tea Party activists stormed congressional offices and the air waves, shouting warnings of incipient tyranny.

In July, Glenn Beck became fixated on the “czars” in the Obama administration, who, he alleged, formed a secret, unelected shadow government devoted to instituting socialism. Among his first targets was Jones, dubbed the “green jobs czar.” Initially, it was about his connections to the Apollo Alliance, but as the teabaggers got to digging they uncovered youthful radicalism, some intemperate humor, and the coup de grace, Jones’ name listed on a 9/11 conspiracy site. There was a spectacular feeding frenzy, and in early September, Jones resigned from the White House.

He has moved on now, working at the Center for American Progress, getting ready to teach a class at Princeton, and speaking at conferences and other events. “This is probably my last interview about the past,” Jones says. “I really do want to remind people that I’m not Paris Hilton.” It’s the path forward, the solutions, that interest him, now as ever. But in the name of helping his supporters and others digest what happened, he spoke to me about his return to his father’s values, the lessons he’s learned from the last year, and why he views the whole incident as “friendly fire.”

(In part two of our interview, Jones speaks about the policies and projects he’s working on and his hopes for the future.)

——

Q. Are you a 9/11 “truther”?

A. No, I’m not. What I believe about 9/11, what I think pretty much everyone believes about 9/11, is that it was a conspiracy by Osama bin Laden and Al Qaeda, and nobody else, to hurt America.

I learned a tough lesson. Back in 2004, people came up to me at a conference, saying they represented 9/11 families and wanted my help and support. I said, “Sure, I’m happy to help any way I can.” I didn’t know their agenda or anything about what they were doing. They just, based on that verbal assurance, went and put my name on a website. They did the same thing to Paul Hawken and Jodie Evans. None of us ever saw the website or their atrocious, abhorrent language. They didn’t have a signature from me. But by [the time all this came out], we were in something of a media firestorm. Even progressives who had stood with me were whipsawed by all that.

Q. Are you a communist?

A. No, I’m not. That’s the plain reading of the article everybody points to, where I talked about how those ideas were part of my past. I gave a speech at the Network of Spiritual Progressives in 2005 where I talked about the fact that I literally, physically burned out on the politics of outrage and confrontation. For the better part of a decade, I’ve been the No. 1 champion of free-market solutions for poor people and the environment. I have a best-selling book and hundreds of speeches and interviews that attest to that.

That said, I’m never going to apologize for my passion for the underdog, in this economy and the next one. The government has a role to play. It’s got to get on the side of the problem-solvers. The big polluters still get all the breaks; that’s got to stop.

Q. Are you angry about what happened?

A. What I try to remember is that the whole country’s going through a process. We’re going to be a very different country in 20 years. That brings up a lot of fear and a lot of anger. People on both sides of the political spectrum are going to make mistakes. In my heart, I see these noisy attacks on me as friendly fire. These are my fellow countrymen and women, who don’t want to see this country continue to suffer. I feel exactly the same way.

I have some patience with all the yelling. I already went through the politics of outrage and confrontation, and for me, I know it doesn’t work. I’ve found a different place to stand. There’s a meeting point for good people in this country, whatever political party they are in. It has to do with making America stronger for the long term, making sure we’ve got our fair share of the next century’s good jobs, making sure we’ve got clean air, clean water, a safe planet for our kids, and we’re respecting creation.

Q. When it all kicked up, did you consider getting out and trying to defend yourself more publicly?

A. I thought it was important, at that moment in the president’s journey, for him to be able to have the conversation he needed to have with the American people without me trying to jump into the frame. You have to remember, we were at a very delicate moment in August and September. The president of the United States was trying to make sure that people who don’t have enough money for doctors get the help they need. Suddenly he runs into this buzz saw of wild accusations of socialism, he’s creating death panels, all kinds of stuff. I felt like he needed to be able to speak as clearly as he could about America’s future and not about my past.

Q. I’ve heard from lots of your supporters who were disappointed by the way it went down. What do you tell them?

A. I had six months in the White House to work on almost everything I’d ever dreamed of working on. Nobody, not even my fiercest critics, criticized the job I was doing, or anything I said, while working for the president. They had to dig up and distort stuff from before I even went to D.C. So I did a good job and had a good experience. Beyond that, we’re all learning: the president’s learning, the administration’s learning, I’m learning, the movement for hope and change itself is going through a big learning process. How I felt about it was, if I’m going to make a mistake, I’d rather err on the side of giving the administration a clean shot at trying to have the conversation they wanted to have. People have a difference of opinion about that, and I understand them.

But I also have to say, having spent six months in the White House, your mindset is very different. It’s like being in an airplane with turbulence: if you’re a passenger on the plane, you have a very different experience; I was in the cockpit for six months. My love of country, which was already tremendous, was just a thousand times deeper every week. It’s very easy for activists to say, hey, just get out there, put your fingers in people’s faces and set everything right. The question is, how does that actually work? There were bigger goals at stake.

Q. You were obviously made into something of a caricature for a while there, as though you hadn’t changed since your angry youth. How have your values evolved over the years?

A. As a kid, I hated seeing bullies in the neighborhood hurting people, or animals being mistreated, that kind of stuff. My whole life I’ve been asking, what are we going to do about the underdog, the people who are being mistreated and left out? My questions have not changed since I was a small child. But as you get older, your answers change. When I was in my 20s, I had the typical answers of most activists in their 20s living in the Bay Area. And now I’m in my 40s and I have a different set of answers.

I worked through different sets of solutions, trying to make a difference for people who are poor and disadvantaged in this country. Police departments in the Bay Area in the mid-90s were having trouble with some officers repeatedly violating the law; I saw that as a problem, went to the state bar association, got licensed, and designed a relational computer database to try to better track problem officers and precincts. Then, at the Ella Baker Center, I created something called the Books Not Bars campaign to reduce the number of kids who were going to prison.

Working on the ground in tough neighborhoods, I found that, from an intellectual and ideological point of view, just giving people stuff doesn’t solve the problem. People want and deserve the dignity of working and earning their way to a better life; it’s not just about redistributing stuff at them.

My father’s life kind of bore that out. My dad grew up in abject poverty and he worked his way out of it. He was a police officer in the military, then he came home and became an educator. I grew up in a super-patriotic household. Like a lot of kids who grow up that way, when I got out in the world and saw homelessness and discrimination, a lot of the things that didn’t look like “liberty and justice for all,” I was heartbroken. I went in a very angry direction, rebelled against my dad and everything he taught me for a while.

I couldn’t hear it when he was alive, but what my dad always used to say to me was people have to climb their own ladder out of poverty. What society has to do is make sure there’s a ladder for them to climb. Doing the work that I did, I saw that was true. The youth programs that were the most generous were producing the worst results. The youth programs that were the most demanding were producing the best results.

There’s also a spiritual dimension to my evolution, which is hard to talk about in mainstream politics. I burned out, not just from a political point of view, but from a spiritual point of view, on a lot of my earlier positions. You go around and try to get people worked up about how oppressed they are, and how terrible the system is, and if you’re successful, you just manage to make people more angry, depressed, and frustrated. I could talk with you for hours about everything I was against, but I couldn’t say anything I was for. At a certain point, if you’re going to do this kind of work, 12- and 18-hour days with some of the poorest people in the country, who have the toughest problems, you have to know what you’re working for, not just what you’re working against.

I felt unable to sustain the level of anger that some of those positions required. I felt, in my own life, the need for hope and inspiration and solutions. So I kind of switched from diesel to solar. It was in that journey that I discovered practical, green business solutions. I discovered that I could do a better job describing what I was for. I reconnected with my own faith, I started a family, I did a number of things that brought me back to my dad’s values. I think it’s a typical American story in a lot of ways, a prodigal son story, coming back home to the values I was raised with, but trying to apply them in a different context. My commitment to solutions for poor and disadvantaged people has not changed, but I’ve moved from righteous indignation to a healthier place.

I think I have the right to be evaluated based on who I am and who I am becoming. I would say that for anybody in American politics. If anybody in American politics, after all we’ve been through as a country over this past 10 to 15 years, has exactly the same view about everything they had in the mid-90s, I question their fitness to lead.

Q. The people who were criticizing you loudest are the ones who do have exactly the same ideas they had 15 years ago.

A. It’s interesting that some of my critics are fellow Christians and people who are not always, by their own admission, living lives that reflect their deepest values. I would hope they could “forgive me my trespasses.” But I won’t take second place to anybody in terms of my love for this country. I work to try to get the American dream realized for people whom a lot of my critics will never meet, never even drive through their neighborhoods. I didn’t do it for a weekend; I’ve been doing it for almost 20 years.

At the end of the day, a certain set of people will be critical of anybody with progressive ideas. They’ll take the first opportunity to walk away from the conversation. But I don’t think that’s most Americans. I do think other folks who are committed to market solutions at some point should take yes for an answer from me.

Q. What has the episode taught you?

A. If you want to play a leading role on challenging issues, you have to take responsibility for how you are going to be heard. To the extent that I sometimes use humor or colorful language to make a point to an audience … you’ve got to be aware that there’s always a bigger audience.

It used to be, as you went through these stages in your life, you could go to the next town and start over. The only person you were accountable to besides yourself was, if you were a person of faith, God. The line of grace was vertical, between you and your creator. Now, in this age of YouTube and Google, all of us are leaving digital bread crumbs behind of the person we used to be. Anything you do or say, some silly thing you did at a college party if somebody had a cell-phone camera, can be seen by everybody, forever. You can know more than you ever wanted to know about pretty much anybody.

It requires more wisdom of society. The line of grace now has to be horizontal. We have to learn how to forgive each other and extend a certain amount of empathy as we all grow up in front of each other. At some point, there’ll be enough people who have had these “gotcha” experiences, and we’ll hit a tipping point. We’ll have a different level of tolerance. But it’s too early. We’re still too new to this, we don’t have the language, customs, and rituals to be able to handle all this stupid stuff we can learn about each other.

My commitment to the country and to a solution-based, love-fueled politics is pretty sturdy. At no point did I let go of any of that. I had thousands of defeats and only one victory. The victory was this: I’m not mad at anybody, I don’t hate anybody. I’m still committed to solving these problems from a good place in my own heart.

I’m still learning how to make the kind of differences I want. I’m not a politician, I’m not running for office, so I have more freedom to take on tougher causes and make more challenging connections. But I don’t have total freedom. At the end of the day, I want to help build bridges. The communities I’m concerned about need more friends and fewer enemies, and I’ve got to be aware of that. If I’m not effective, the people who suffer are not primarily me, it’s the people who need green jobs but won’t get them.

I had a year where all my dreams and all my nightmares came true. That’s a lot of living in a short period of time. Where it left me is much, much more compassionate and with a deeper patriotism. My faith is deeper. My compassion for the pain in this country, whether it expresses itself as the Tea Party movement or as the Coffee Party movement, is much deeper. I don’t see things as simply as I used to. I’m looking forward to spending a year teaching, reflecting, and speaking out where it’s appropriate. But in terms of my hopes for the country, and my contributions, I feel like I’m just getting started.

This is probably my last interview about the past. I really do want to remind people that I’m not Paris Hilton. The only reason people cared about me in the first place, before some people made an issue of every dumb thing I ever said or supposedly said, was that I’m a guy with some solutions and some passion for them. That hasn’t changed.