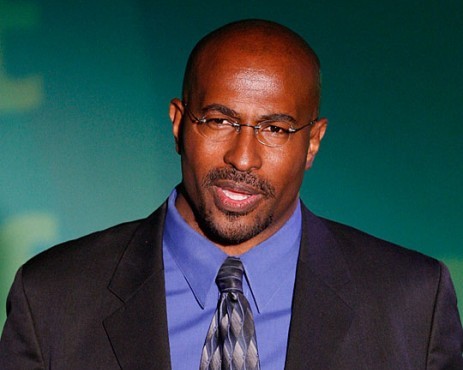

Van JonesIn part one of our interview, Van Jones discussed the evolution of his values, the controversy that’s surrounded him over the past year, and his ongoing commitment to “love-based politics.”

Van JonesIn part one of our interview, Van Jones discussed the evolution of his values, the controversy that’s surrounded him over the past year, and his ongoing commitment to “love-based politics.”

Here, in part two, we turn to the road forward: the policies and projects he is working on for the next year. Along with his usual vigorous speaking itinerary, Jones will be teaching a class at Princeton and working at the Center for American Progress, developing policy tools for legislators keen on helping along a green economy.

——

Q. What’s the Princeton class going to be about?

A. Environmental policy and politics.

Q. Have you taught or lectured before?

A. Not in that kind of setting, but I come from a family of educators. My granddad was a college president at Lane College in Jackson, Tenn. Both my parents were school teachers. I’m not shy about ideas. I wrote a best-selling book on green jobs and traveled the country lecturing on the green economy for years before I moved to D.C.

Q. What sorts of ideas are you going to work on at the Center for American Progress?

A. Three things I’m passionate about. One is what’s now being called Home Star, or Cash for Caulkers. When I was at the White House, I ran an interagency process called Recovery Through Retrofits that developed and teed up a lot of these ideas. By building up a new sector of our economy, home energy performance, we can create a whole bunch of jobs and save a bunch of money. We turn wasted energy into wanted jobs. That’s now going to be a part of the jobs bill, but I think we should continue to push to make sure it passes in the most robust form possible. We have a hundred million American homes that could be upgraded in terms of energy performance. If it’s financed properly, all that work can pay for itself over time, through energy cost savings.

No. 2, for our industrial heartland, we need a strong renewable energy standard [RES], say 25 percent of all American energy to be produced by renewables by 2025. That gives the wind industry in particular certainty of demand, so they will invest in building factories here and putting manufacturing workers to work here. If you don’t do that, all the investments are going to happen in Asia and the only green jobs Americans will have will be installing Chinese technology. Wind turbines will be built overseas, and we’ll bring them here and stick them in the ground. Solar panels will be made overseas and we’ll bring them here and bolt them to a roof. You’re not going to get a bunch of jobs out of that. You get jobs out of manufacturing the stuff here and putting it up here, and also shipping it out around the world. That’s not going to happen with even a good cap-and-trade bill by itself. When you get that kind of RES, you turn the rust belt into a green belt.

Lastly, we need some kind of Green Enterprise Zone legislation that will reward green and clean energy companies for locating and hiring in tough neighborhoods and communities. If you’re a green entrepreneur and you want to go to Appalachia, or you want to go to a Native American reservation, you should be able to get some tax credits or other support for making that choice. Right now you can scrape together a couple different packages and programs, but there’s nothing designed for the particular challenges of the clean energy sector.

Q. Do you still consider yourself a part of the grassroots movement?

A. Yes, absolutely. Just last week I was working with grassroots leaders in Flagstaff, Arizona and Detroit, Michigan, formulating strategies for advancing green jobs on the ground. I am especially proud to still be involved as a senior advisor to Green For All, which I helped to found in 2008. The new CEO there, Phaedra Ellis-Lamkins, is simply amazing and has taken that organization to new heights. They are now advancing projects in dozens of cities, linking with celebs, and moving Congress. The real fight for green jobs is happening on the ground, every day, in cities and towns across America. I am happy to be a part of that forward momentum.

In terms of political ideology I’m probably more moderate than most people think, but I am still a life-long opponent of corporate abuses, especially in the incarceration industry and by the big polluters. I am still seeking a deep transformation of our economy so that we create more jobs and stop poisoning and baking our planet. I am still fighting to eliminate extreme poverty.

Those are big goals. I just think we have to be wise enough to know that getting there will require a mix of government intervention and market forces. Plus a whole lot of community-level cooperation. Plus a ton of individual responsibility. Plus a lot of prayer. The government can’t just wave a magic wand and fix all this stuff. Government has to get the public rules, investments, and incentives right, but then the private sector will step in to become the big engine driving change.

I know for sure that no single class, race, or political party can effect this level of change all by itself. If we are going to revive the economy and rescue the earth, we have to work together across the old lines of class and color and ideology. So that’s where I stand. That’s what I’m about.

Q. You and others in the Bay Area in the early ’00s were insistent that green jobs be tied to equity, specifically targeted to disadvantaged communities. That seems to have faded a bit from the broader conversation. Why do you think that is?

A. When we first started the conversation, we had a functioning economy and unemployment was relatively low. If you were going to grow the economy in a green direction, you absolutely needed to pull new people into the workforce. You saw that happen in California in 2006, 2007, when the solar industry started taking off. Homeowners were facing three- to six-month delays getting their solar panels put up. There just weren’t enough trained workers. So the evaluation was, we’ve got a lot of work that needs to be done and we have a lot of people who need work, mainly people who have been locked out of the workforce for awhile. There was an objective basis for bringing chronically poor, unemployed folks into the green economy — we were already experiencing a labor shortage in green sectors and fields.

Now you don’t just have the chronically poor, you have the newly poor. You don’t just need to grow the green economy, you need to grow the whole economy. Those factors tend to pull the conversation toward a general prescription for a much broader section of workers. That said, it’s still just as important to focus on those places that most need jobs and make sure that both public policy and private enterprise have impact there. You still have to deal with places like Appalachia, the Native American reservations, the industrial heartland, the agricultural heartland. It’s just that more people fall into the bucket of needing employment.

Q. If you take a global equity perspective, you have to think that dirt poor Chinese peasants need jobs more than almost any American. Yet there’s been an uptick in talk about a competition or “race” with China. What do you make of that?

A. I’m concerned about two things now: one is making sure Americans have a fair share of the global set of green jobs; the other is making sure all Americans have a fair shot at America’s fair share. You can fight for a fair share of the global set of green jobs without being anti-Chinese. You can aspire for your own country to lead, to rely on our own natural advantages, without being protectionist.

I am thrilled that India and China are getting traction economically. They have hundreds of millions of desperately poor people. I want to see them come out of poverty into a green and sustainable economy. And I want the same thing for America. I don’t think one has to come at the expense of the other.

There are good reasons for the United States to be a world leader on clean energy. We have a Saudi Arabia of solar power, not just in the Sun Belt but on rooftops across America. We’ve got a Saudi Arabia of wind power in the plain states, near the Great Lakes, and off our coasts. We’ve got the innovation and investment community, not just in Silicon Valley but also in New England and elsewhere. We’ve got some of the best workers in the world sitting idle in our industrial heartland. Those are all good reasons for us to lead. The reason we’re not leading is we’ve got dumb policies, while our friends in Asia are putting in place smart policies. A friendly competition between the United States and China, where both put in place the best policies and rush ahead to come up with the best technologies and the best jobs, could be good for the world.

It’s a leadership challenge to make sure we don’t fishtail over into anti-Chinese demagoguery or jingoism. We have to avoid that. The ideal is a cross between a global partnership and a friendly rivalry.

But we can’t be partners with China, can’t be partners with Asia, in repowering the world on a green energy basis if we aren’t aggressively moving in that direction ourselves. This is one reason I’m confident and somewhat patient. Nobody believes we’re going to be able to tax-cut our way into an economy that works any more. A pretty broad cross section of economists, left and right, are saying we need to stop borrowing and start building again. We’ve got to start selling things to people around the world and not just importing and racking up debt.

Q. You’ve had that vision of consensus for a while, and it overlaps with Obama’s appeal in 2008. But the experience of the last year seems to point in the other direction. One party is spinning farther and farther out. Is that going to end?

A. I think people are overreacting to the past 12 months. You have red states and blue states with cities and state governments that are already driving in a clean energy direction, creating a bottom-up constituency of elected representatives, business leaders, and labor leaders. They’re already in motion. It will be increasingly safe political ground for the people in both parties. You have leadership in the Republican party, Lindsey Graham, Arnold Schwarzenegger, and others pointing in the direction of smart climate and energy policy — even in the middle of this horrible food fight and gridlock. When the dam finally breaks and this stuff starts happening, it will be good for red states, blue states, and both parties.

The movement for hope and change is going to go through its own metamorphosis and reemergence — first from opposition to proposition, now from inspiration to implementation. That’s a learning curve for elected officials; it’s also a learning curve for a movement. We should be tough on our problems but easy on each other, because this is not easy to do.

Take a step back and ask, where was the country a year and a half ago and where is it now? There’s been so much progress it’s almost unrecognizable. If you zero in on any particular bill or any particular subcommittee or any particular tactic, you can get depressed. But on any given day, the administration’s getting tons of good stuff done. The fact that we have a functioning economy, even though recovery isn’t as strong as we’d like it, is itself a huge victory. The fact that the EPA is actually living up to its name again. The Department of Labor is concerned about working people. HUD went from a joke to becoming one of the best-led agencies in the federal government.

What we’ve got to do is not despair. We went from despair to hope in 2008, expecting to go from hope to change in 2009. But change didn’t come instantly and so some people were wanting to go from change all the way back to despair again, in 12 months. I think that’s silly.

Q. In the past, you and I have talked about why politics seems so broken and stalled. Now that health-care reform has passed, do you see the political landscape differently?

A. In hindsight, the fact that it took a year to get this done is not going to seem so bad. I think it should restore our confidence that our movement can achieve important milestones. Obviously we need to work harder and more consistently

Part of what we’ve got to do is recognize that the president ran on the slogan, “Yes, we can,” not “Yes, I can.” The “we” kind of fell out and the grassroots started acting like it was all about him, all about one person, like “Yes, he can.” Before the immigration march, the last time I saw people in the streets was for the inauguration a year ago. People couldn’t have come out with “Yes, we can” and “We are one” banners when the opposition kicked up at a street level last fall? Finally, now you see the Coffee Party movement starting up. People are rolling up their sleeves again. I think the hoperoots have returned. Obama is back, but the hoperoots are back as well.

Q. It has been quite a ride.

A. Who you telling? I know this. If anybody in American politics might qualify for the despair and bitterness program, I might. I had as rough a 12 months as anybody and I’m not throwing my hands up. I’m as committed to the politics of hope as ever. I’m as confident as ever that we can get to these solutions. We’re just getting started.