This story was originally published by Honolulu Civil Beat and is republished with permission.

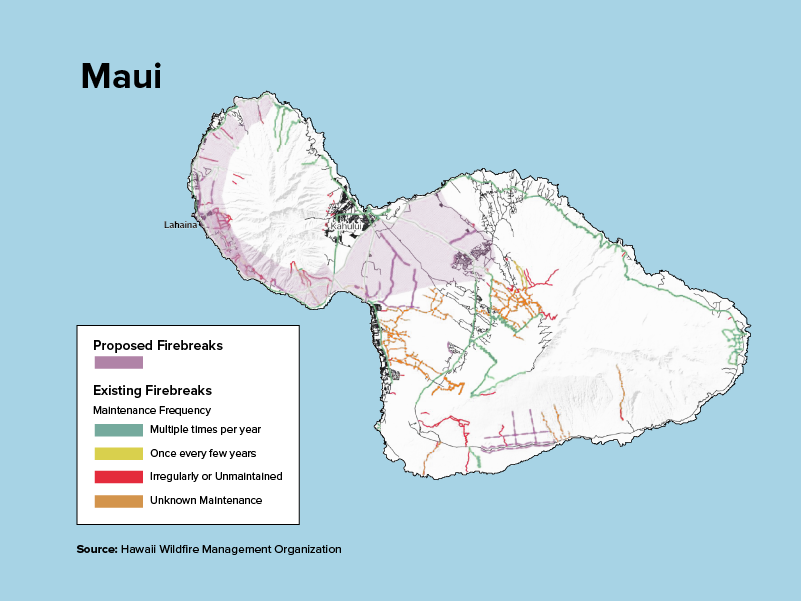

Hawaii maintains a network of firebreaks to keep wildfire from spreading, but that system includes hundreds of miles of gaps that need to be filled to protect communities around the state.

Public and private land managers dealing with the danger face bureaucratic barriers and a lack of money and collaboration.

Managing land to reduce fire danger took on increased urgency after the Aug. 8 wildfires on Maui, including the conflagration that leveled Lahaina and killed at least 115 people.

Both firebreaks and fuelbreaks are used to slow or halt the spread of wildfire. Firebreaks are generally wide belts of bare soil, but roads and rivers can serve the same purpose. Fuelbreaks are actively managed strips of land with minimal vegetation, intended to weaken the intensity and spread of fire.

Hawaii has roughly 4,300 miles of breaks, but needs approximately 350 miles more — accounting for some 400,000 acres, according to 2019 data collected by the Hawaii Wildfire Management Organization.

It’s doubtful that firebreaks around Lahaina on Aug. 8 would have stemmed the spread of the West Maui fire, given the high winds, HWMO co-executive director Elizabeth Pickett said. But the tracts play an integral role in helping firefighters access hard-to-reach areas to dissipate fires’ intensity.

As far back as 2018, fire officials and land managers identified a need for an additional 350 miles of breaks during meetings with representatives of 128 private and public groups and HWMO.

But because those breaks cross federal, state, county, and private lands, there must be collective buy-in and coordination to make it work, as well as money to pay for it all, Pickett said.

“Fire doesn’t recognize fence lines and ownerships and jurisdiction. So we need our fuels management to make sense at the land level,” Pickett said.

The 2018 meetings resulted in an assessment of the state’s needs that has informed much of its work on vegetation management until now.

Building breaks

But the effort has not received enough attention or money, officials say.

Building a firebreak on public land is expensive. The Department of Land and Natural Resources says it can’t afford to do it short of an emergency.

DLNR, which manages 26 percent of the state’s land, maintains just over 320 miles of breaks statewide but only cuts them during active wildfires. The department says the regulatory costs of protecting environmental, cultural, and historic resources make it unfeasible except during emergencies.

Those regulations are waived during active fires, when trained “dozer scouts” from DLNR’s Division of Forestry and Wildlife guide bulldozers to cut ribbons in the landscape to stop fire without destroying important resources.

The result is an “ad hoc network” of firebreaks and fuelbreaks, according to DOFAW forester Michael Walker.

To link it all together across boundaries will take time, staff and funding beyond DOFAW’s current capabilities, Walker says.

A bill that was killed this year would have set aside $3 million over two years for DOFAW to connect Hawaii’s breaks. Even that would have fallen far short, Walker says.

“And it’s not just us — forestry and wildlife — that need fuel reduction funds. It’s ranchers, farmers,” Walker said in a July interview before the Lahaina fire.

Farmers and ranchers are key players in preventing wildfire because they actively manage the landscape, either through grazing or crops. Land no longer used for these purposes has contributed to the spread of wildfire in recent decades.

Unused land has fostered the spread of invasive grasses, many thriving under drought conditions.

Much of this land now borders development.

“The bulk of the housing in Hawaii these days is built on top of old plantation land,” Walker said. “So they’ll develop a piece of it, but then the rest of it is still surrounded by fallow ag land.”

A week ago, a three-acre wildfire threatened three homes in Oahu’s Makakilo, a community that has consistently raised concerns over its single evacuation route. It came up again recently, in the aftermath of the Aug. 8 Maui fires.

On top of evacuation concerns, the Honolulu Fire Department said in a press release that there are too few firebreaks in the unmanaged land bordering the community.

Because wildfire does not respect property lines, it has been a focus for HWMO, which has been working on bolstering communication, funding, and coordination across the state.

That was the goal of HWMO’s 2018 meetings: to test and establish an “all hands, all lands” approach in Hawaii, according to co-executive director Pickett.

HWMO has tested community-based, cross-boundary fire mitigation projects on five of Hawaii’s major islands, allocating $22,000 to each project. They ranged from grazing sheep in Waianae to building a break in Kawaihae on Big Island.

But Pickett recognizes that her relatively small organization has only been able to focus on the community level.

“We want to think about what makes sense across boundaries,” Pickett said.

Not every landowner has been willing to take part. HWMO has focused on working with the willing.

But more needs to be done, including improved fire codes, legislation, and enforcement.

“Where’s the gap? Accountability,” Pickett said.

Taming the vegetation

In light of the Aug. 8 fires, county and state lawmakers appear resolved to stem the risk of wildfire in Hawaii.

Last month, Honolulu Mayor Rick Blangiardi ordered a review of Oahu’s fire risk, including firefighting assets and capacity, unaddressed needs and system vulnerabilities.

Last week, the Hawaii House of Representatives established working groups to focus on several wildfire topics to inform bills in the next legislative session.

One of those groups will be focused on wildfire prevention.

One of its 16 members, Rep. David Tarnas, believes the state should coordinate the establishment of a robust network of breaks and creating incentives for vegetation management, because it all costs money.

The government entity mandated to do the work — DOFAW — has been underfunded for years, Tarnas said.

“We can’t just leave it to a nonprofit,” Tarnas said. “You know, we have to step up as a state and fully fund our natural resources and fire protection program.”

Civil Beat’s coverage of Maui County is supported in part by a grant from the Nuestro Futuro Foundation.

Civil Beat’s coverage of climate change is supported by the Environmental Funders Group of the Hawaii Community Foundation, Marisla Fund of the Hawaii Community Foundation and the Frost Family Foundation.