In all our excitement about the growth of urban agriculture here in the U.S., it can be easy to forget that the tradition of farming in cities has a long international history. “We feel like we’ve reinvented the wheel, but urban farming has been going on as long as cities have existed,” says Karney Hatch, a filmmaker who spent five months traveling the globe to gather material for a documentary about urban farming beyond our borders.

Films about gardening in U.S. cities are practically a dime a dozen these days, but what could we learn from projects in Shanghai, Havana, or Accra? Hatch plans to start post-production work on his film next month, so it’ll be a while until we get all the answers. In the meantime, we couldn’t resist calling him up in for a preview of what he found.

Q. What places stood out to you for their urban farming efforts?

A. In terms of really fascinating stories, I would say Ethiopia and India. In Calcutta, you ask yourself, “Why are we not doing that in the developed world?” Calcutta does not have a sewage treatment plant. They have a big canal full of waste that leaves the city flowing east toward the Bay of Bengal. They use that waste stream to feed traditional farms as well as fish farms. The waste flows out into these huge ponds and settles to the bottom and feeds algae, and the fish feed on the algae. It’s an ecosystem. [Recycling waste water] is actually happening here in the U.S. more than you would realize, but I think we have to stop being so squeamish. The fish aren’t directly eating poop.

Q. What’s the attitude toward urban farming it in other parts of the world? Is it seen the same as elsewhere?

A. When I first went to China and told my translator that I was looking for urban farms, there wasn’t really a translation for that, because culturally it’s just what they do.

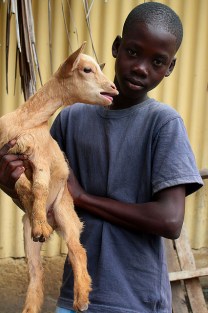

Cities in the developing world are growing exponentially right now. There [are] huge inflows of people, and for a lot of them, once they get to the city, real life is not quite as easy or exciting as they thought it would be. A lot of them end up living in slums. In Accra, Ghana, I met young farmers all apprenticing under old urban farmers, working on their plots as hired hands. They were all super excited to have a decent job instead of being stuck unemployed on the street.

In the U.S. a lot of times people are taking up urban farming as kind of a fun hobby, which is great — the more food being produced the happier I am — but they’re not depending upon it for their survival. Community gardens are fine, but I think if we’re really looking at a way to scale it up, you have to look more at the for-profit model.

Q. How does farming for survival change the nature of the practice?

A. It’s more productive and it seems to lead to much stronger communities. Because if you’re growing food to survive, you have a strong motivation to grow really well. You ask the people around you what their secrets are. You all work toward this common cause. When your caloric intake doesn’t depend on it, the stakes are not as high; you’re not forced by necessity to work together.

Q. How can we encourage innovative urban farming models in the developed world, then, where the stakes are not as high in terms of basic survival?

A. We’ve gone through really hard times before, in the Great Depression and World War II. We’ve shown that during hard times we can pull together and grow a lot of food in our cities [see: victory gardens]. And times are hard now; a lot of people are suffering. The economic model is there to create a profitable business doing this — all we have to do is spread the word.

It’s so important that kids are exposed to this stuff really early on, so it’s not some weird thing. If you are exposed to [farming] at your grade school or your middle school, you realize that it’s easy and beats the heck out of sitting behind a desk. Most of us are not so far removed from it; our grandparents and our great-grandparents lived on farms. But now we’ve moved into cities; our food is produced far from where we live. If we want to start turning it the other way, we have to start with the children. And old people. If you go to China, it’s not uncommon to see people who are quite elderly out there spending most of their free time growing food. They’re serving an important function, and they’re making extra money; it’s just win-win-win down the line.

Q. What can we in the U.S. learn from other countries about how to raise food in cities well?

A. To [build] a mature urban agriculture system in the U.S., you would end up pulling from a lot of different examples. Cuba is kind of the famous one. One of the things I’m getting excited about is animals in the city. Especially fish — there’s a lot of aquaponics getting started. In 1996 I was in China and I saw [people] harvesting freshwater eels out of the rice paddies. It’s something we would [almost] never do in the U.S., because we’re like, “I’m a fish farmer, [you’re] a rice farmer, we do not mix.” In China it’s just natural.

There are some cities in Africa where somebody has a plantain tree, and [somebody else has] pineapple, and corn, and there’s a herd of goats going down the street; it’s all kind of integrated together. We’re a long ways from that, but once you’ve seen it, it’s not that hard to imagine having that sort of integrated system in some of our cities in the U.S.

Q. How did you find the urban farmers you talked to for the film?

A. I got in touch with some experts in the field, just to get advice on where some of the most exciting projects were going on. Sometimes, by chance, somebody would get ahold of me and say, “Look at this amazing project … ” When I was in Accra I wanted to interview some urban goat farmers, so one afternoon I just followed the herd of goats until they went home. In Shanghai, I was having trouble finding urban farmers. I actually went to satellite view on Google Maps, because if you zoom in far enough you can see rows of plants. I found farms that way. I would get on the subway and get as close as I [could] and then get a taxi. I had this map, and I had circled urban farms on the map, and the taxi driver was like, “If you want to go see a farm, we have to go way outside the city.” Five minutes later we’re standing with a second-generation urban farmer on the same location his father and mother had been farming since the 1940s. It’s that way a lot of times — it could be happening a lot closer to where you are and you don’t realize it’s there.