Cruise and cargo ships around the world are cleaning up their dirty smokestacks, installing systems that prevent harmful pollutants in their exhaust from escaping into the air. Yet much of that pollution is winding up in the sea instead. And so a solution meant to reduce smog, experts say, is leaving a potentially toxic trail in its wake.

Thousands of ships use exhaust cleaning systems, or “scrubbers,” compared with hundreds of ships just a few years ago, as companies face rising pressure to tamp down on their pollution. International regulators now require vessels to burn low-sulfur fuels at sea, while local authorities are cracking down on emissions close to shore. Scrubbers offer a middle ground, allowing ship operators to keep burning sludgy, sulfur-laden “bunker fuel” and still comply with air quality rules.

The problem is that those ships are expected to dump at least 10 billion metric tons of what’s known as wash water — the contaminated byproduct — into seas around the world every year, according to a first-of-its-kind study from the International Council on Clean Transportation, a nonprofit research group.

About 80 percent of that wash water ends up close to shore, including near major cruise destinations in the Bahamas, Canada, and Italy as well as in ecologically sensitive areas such as the Great Barrier Reef, the ICCT’s study said. The wash water can be a nasty cocktail of carcinogens from the fuel oil, heavy metals that harm marine life, and nitrates, which can worsen water quality in shallow waters. Instead of flowing into the open ocean, where pollutants might disperse, much of the wash water often pours into places that function more like bathtubs.

“It means that every year, quite high concentrations will accumulate in these areas and will be growing and growing,” said Liudmila Osipova, the study’s lead author and an ICCT researcher in Berlin.

Separate scientific research has shown that scrubber wash water can be acidic and poisonous to some marine life, though the overall effect on coastal environments and communities isn’t fully understood. “We don’t know what kind of consequences that will have,” Osipova said.

Only a fraction of the global shipping fleet — roughly 8 percent — uses scrubbers. Other vessels have switched to cleaner-burning but more expensive petroleum products like “marine gas oil.” But scrubber adoption continues to grow, particularly among giant cargo vessels and cruise ships with huge appetites for fuel. The bigger the vessel, the bigger its scrubber, and the more wash water the system will ultimately discharge.

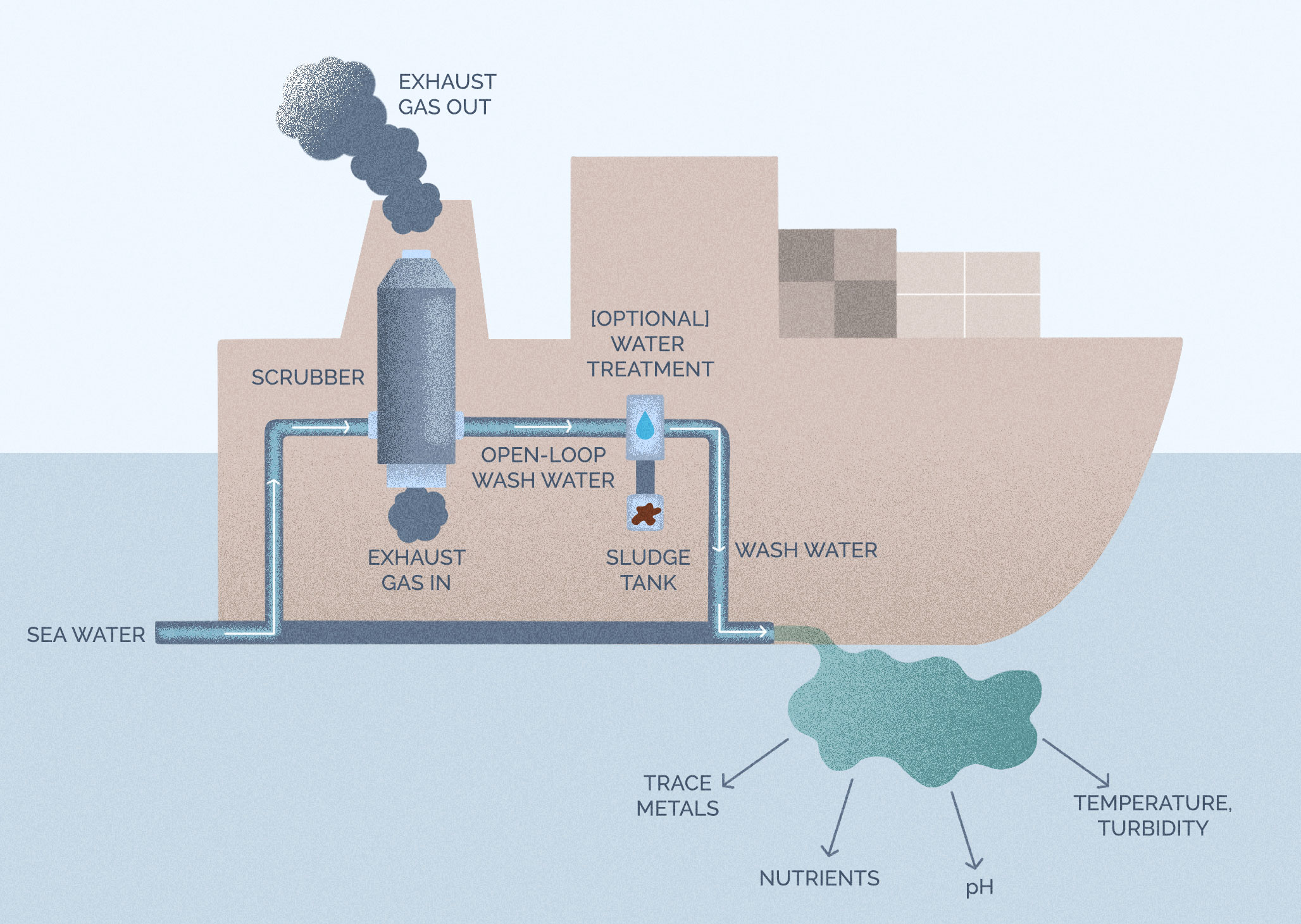

Most scrubber systems are “open-loop,” meaning they mix seawater with exhaust gas, filter it, then discharge the resulting effluent. “Closed-loop” systems treat and recirculate their wash water and dispel a smaller amount, but fewer shipping companies use them because they cost more to install and operate. Until ICCT researchers studied some 3,600 scrubber-equipped ships, there wasn’t a solid sense of how much polluted water these systems produce around the world or where it winds up. Some 700 more ships now use scrubbers since the research data was collected, so the volume of wash water is likely much higher than estimated, Osipova said.

For environmental groups, the study compounds their broader frustration with the industry’s seemingly tepid efforts to address climate change. Cargo shipping is responsible for nearly 3 percent of the world’s annual greenhouse gas emissions. Yet rather than pursue technologies to replace bunker fuel, some shipowners are spending millions of dollars to install equipment that addresses one problem — air pollution — but does nothing to advance the industry’s decarbonization efforts, said Dan Hubbell, manager of the Ocean Conservancy’s shipping emissions campaign in Washington, D.C.

“We’re facing a truly global crisis, and it’s the kind of thing that requires bold solutions,” Hubbell said. “A piece we’ve struggled with is the industry’s preference for short-term fixes.”

Proponents of scrubber systems pushed back against the ICCT study and other criticisms. The Clean Shipping Alliance, an industry group that includes the cruise giant Carnival, said the report’s estimates of 10 billion tons of wash water are “greatly exaggerated.” The alliance pointed to industry-funded research that suggests that wash water has the “same overall water quality” as the seawater it returns to. In a statement, Capt. Mike Kaczmarek, the alliance’s chairman, said that scrubbers have become “a successful bridging solution to carbon neutrality.”

Independent research had already raised flags about the effects of scrubber wash water on the marine environment. Last year, a study on ships in Belgium found their scrubber discharges to be acidic, with elevated concentrations of metals like nickel, copper, and chromium — all of which can hurt fish and other marine life. In April, the Swedish Environmental Research Institute found that wash water from North Sea ships has “severe toxic effects” on the zooplankton that serve as food for cod, herring, and other important fish species. Researchers suggested that ships’ scrubber systems might serve as a “witch’s cauldron,” meaning that chemical compounds brew in a hot, acidic environment and become more toxic together than they would if taken individually.

Kerstin Magnusson, an ecotoxicologist and co-author of the Swedish study, noted that scrubber wash water doesn’t affect all species the same, and it may be less toxic in certain environments than others. But research on the topic is still relatively limited, in large part because scientists have trouble getting their hands on wash water samples. “Ship owners don’t want us to collect it,” she said. “They think we are seeking to find adverse effects, but this is not the case.”

Given such uncertainty, governments worldwide are taking steps to protect the waters they control. Thirty countries and ports have banned or put limits on scrubber wash water in their jurisdictions, including major shipping countries like China, Singapore, and Norway, as well as authorities in charge of the Panama and Suez canals. In the United States, California and Connecticut have scrubber-related restrictions. And in Washington state, officials are considering a proposal to prohibit wash water in the Puget Sound, a busy cruise hub that’s home to threatened orca whales and Chinook salmon.

The Port of Seattle last year banned cruise ships from dumping wash water “out of an abundance of caution” to protect fish and wildlife habitats near the Seattle waterfront, said Alex Adams, the port’s senior manager of environmental programs. “Until we can learn more about the impacts of wash water discharges, we’re going to continue this prohibition,” Adams said. In response to the policy, most cruise ships now plug into the port’s shoreside electricity to avoid running their scrubbers.

Groups like Ocean Conservancy and Stand.earth are calling for a blanket ban on scrubber use within U.S. and Canadian waters. The ICCT recommends that the International Maritime Organization — the United Nations body that regulates the shipping industry — prohibit ships from using scrubbers to meet environmental protocols and phase out scrubbers on existing ships. That might encourage companies to get more of their vessels to run on low-sulfur fuels like marine gas oil until fossil fuel alternatives such as green methanol, hydrogen, and ammonia become viable.

Without tighter restrictions on wash water pollution, or stronger requirements to reduce ships’ greenhouse gas emissions, cruise and cargo ships are expected to continue installing scrubbers. That could lead to even more wash water getting dumped overboard. The way things are going, Osipova said, “We’ll just see more and more emissions of water pollution in the future.”