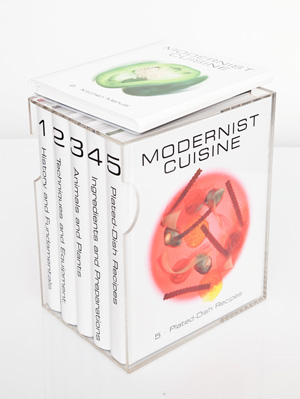

The most expensive cookbook you’ll (n)ever buyNathan Myhrvold’s Modernist Cuisine — in all of its six-volume, 2,438-page splendor — explicitly aims to “reinvent cooking.” Maybe it will; and it will almost surely reinvent a certain kind of high-end book retailing. It sells for a cool $625, and its initial 6,000-copy print run has already sold out.

The most expensive cookbook you’ll (n)ever buyNathan Myhrvold’s Modernist Cuisine — in all of its six-volume, 2,438-page splendor — explicitly aims to “reinvent cooking.” Maybe it will; and it will almost surely reinvent a certain kind of high-end book retailing. It sells for a cool $625, and its initial 6,000-copy print run has already sold out.

Perhaps not surprisingly, Myhrvold and his vast project have not been warmly received by the sustainable food movement. Alice Waters, the influential Berkeley restaurateur, dismissed the high-tech cooking championed by Myhrvold as a “kind of scientific experiment,” adding that “it’s not a kind of way of eating that we need to really live on this planet together.” In other quarters of the movement, the response has been silence. One prominent sustainable-food person told me privately she had “zero interest” in what Myhrvold is up to, a response echoed by several others.

Yet after speaking to Myhrvold on the phone and spending some time poking through Modernist Cuisine (no, I didn’t score a review copy; I was allowed access to an online facsimile of it for a limited amount of time), I’m convinced that Myhrvold does have something to offer the movement: cooking tips, yes, but mainly a theory of food that will be valuable in rescuing food from the forces of industrialization.

That might seem at first glance like an ironic, and foolish, statement. Myhrvold is a tech gazillionaire — he served as Microsoft’s chief technology officer during the 1990s, the decade that saw the operating-software behemoth conquer the universe (including its Wall Street wing). Modernist Cuisine is a kind of glorious rich guy’s vanity project: years in the making, it sprouted in the 88,000-square-foot warehouse of Intellectual Ventures, Myhrvold’s Seattle-based company. Evidently, no expense was spared to create this 40-pound monster of a work — Myhrvold assembled a team of dozens of chefs, photographers, and assistants. Lord knows how much cash went into equipping the vast kitchen/laboratory with the various machines needed to put his culinary vision into action. All told, Myhrvold has said, the project cost him something approaching $10 million. This may be the most elaborate book project since King James assembled his Bible.

Nathan Myhrvold, a modernist manBut for all the technology fetishism on display, Modernist Cuisine is really an art project, as Myhrvold made clear when we spoke. As a writer, Myhrvold chooses his words carefully, and his title’s reference to modernist, and not modern, cuisine is not an accident. He’s referring specifically to the modernist strain in Western art that first flowered among painters in France in the middle of the 19th century. From the beginning, modernist art meant a rejection (or at least a thorough questioning) of the certainties of tradition — not only religious pieties, but also those of the Enlightenment, which was hinged on the idea that all phenomena could be explained rationally.

Nathan Myhrvold, a modernist manBut for all the technology fetishism on display, Modernist Cuisine is really an art project, as Myhrvold made clear when we spoke. As a writer, Myhrvold chooses his words carefully, and his title’s reference to modernist, and not modern, cuisine is not an accident. He’s referring specifically to the modernist strain in Western art that first flowered among painters in France in the middle of the 19th century. From the beginning, modernist art meant a rejection (or at least a thorough questioning) of the certainties of tradition — not only religious pieties, but also those of the Enlightenment, which was hinged on the idea that all phenomena could be explained rationally.

Modernism unleashed a torrent of experimentation: first in painting, then visual arts generally, then in poetry, architecture, theater, music, and novel writing. For all those art forms, radical modernist movements arrived by the 1930s. But according to Myhrvold, food never got its modernist transformation until the mid-1990s, with the rise of the wildly inventive chefs like Spain’s Ferran Adrià and the U.K.’s Heston Blumenthal, followed by their U.S. acolytes Grant Achatz and Wylie Dufresne.

“Adrià and Blumenthal began doing something radically different,” Myhrvold told me. “Under the banner of what became known as ‘molecular gastronomy,’ they threw aside tradition or turned it upside down, and began experimenting with new flavors, techniques, combinations. No one had really done that before in the food world.”

I asked him what had taken so long: Why did modernist cuisine arrive so much later than other forms of modernism? Why did cuisine have to wait until the 1980s to get its James Joyce? And what about the famed turn-of-the-century French chef Auguste Escoffier — why didn’t he qualify?

The dominance of Escoffier is precisely why modernism took so long to take hold in cuisine, Myhrvold replied. “Escoffier was incredibly influential, but he didn’t establish an art form, he created a system,” he said. “In many ways, he was the Henry Ford of the kitchen … he was about managing production and maintaining uniform standards, not individual creativity.”

Myhrvold went on to talk about how Escoffier and his “brigade” system became the orthodoxy against which his radical modernist chefs rebelled — in a much more fundamental way than did the practitioners of an earlier culinary movement, nouvelle cuisine, in the 1970s. “The nouvelle cuisine people did a lot of interesting and important things, but they were really kind of refining Escoffier, not throwing him over … and they explicitly stated that they weren’t modernists.”

Myhrvold’s high-tech labAnd here is where we get to the importance of Modernist Cuisine for the food movement: It recognizes and indeed celebrates food as something much more than mere sustenance, mere slop on a plate meant to keep us going another day. It sees food as an art, as “something that can engage our minds, our senses, and emotions just as profoundly as carefully chosen words and brush strokes,” as Myhrvold writes in a historical essay in the first volume of Modernist Cuisine. Myhrvold’s commitment to food as a sensory and cultural, not merely functional, artifact permeates the book’s volumes, even in their geekiest sections. The photography wouldn’t be out of place at the Museum of Modern Art.

Myhrvold’s high-tech labAnd here is where we get to the importance of Modernist Cuisine for the food movement: It recognizes and indeed celebrates food as something much more than mere sustenance, mere slop on a plate meant to keep us going another day. It sees food as an art, as “something that can engage our minds, our senses, and emotions just as profoundly as carefully chosen words and brush strokes,” as Myhrvold writes in a historical essay in the first volume of Modernist Cuisine. Myhrvold’s commitment to food as a sensory and cultural, not merely functional, artifact permeates the book’s volumes, even in their geekiest sections. The photography wouldn’t be out of place at the Museum of Modern Art.

Compare Myhrvold’s aesthete’s vision of food with the view of, say, the transnational GMO seed giant Monsanto. In a much-heralded and self-congratulatory 2008 document, Monsanto promised to “double yield in its three core crops of corn, soybeans and cotton by 2030” in order to help “feed the world” amid population growth. This is a vision of food reduced to pure commodity, with progress measured by gross output of a few preselected crops.

And that’s been the official government/industry/philanthropic view of agriculture at least since the dawn of industrial ag in the early 20th century. I’ve been reading a terrific book called The Hungry World: America’s Cold War Battle Against Poverty in Asia, by the University of Indiana historian Nick Cullather. The book is an intellectual history of the Green Revolution, the effort funded and engineered by U.S. foundations and aid institutions to boost food production in Asia in the ‘60s and ‘70s. Cullather writes about the invention of the calorie as a unit of food value in the late 19th century, and how it allowed foodstuffs to be reduced to the amount of energy they contained. The precise measurement of calories, Cullather writes, “translated the vernacular customs of food into the numerical language of empire.” It gave rise to the conviction that food was “fundamentally uniform and comparable between nations and time periods … that wheat was uniquely important as an international conveyor of food bulk value.” In short, he argues, calorie-fixated industrialists and bureaucrats began to view food as a commodity, “without reference to taste, ethnic conviction, or social context.”

Of course, the 20th century brought the rise of chemical agriculture designed to maximize the production of calories — and with it, the withering away of food traditions, ethnic and otherwise, across the United States. Thus at the same time Escoffier was rationalizing and regimenting the restaurant kitchen, technocrats were doing the same for the farm field. That same vision of food as purely utilitarian, uniform commodity permeated the original Green Revolution of the ‘60s and ‘70s in South Asia, and it permeates the so-called “Second Green Revolution” now being financed by the foundation of Myhrvold’s old Microsoft boss, Bill Gates.

Soup dumplings as you’ve never seen them beforeThe sustainable food movement has worked explicitly against that agenda; it has tried to re-enchant the eating experience, to restore food’s role as a cultural experience that ties us to our communities and to the Earth. Myhrvold, a Microsoft man and in fact a confirmed techno-optimist (let’s leave his promotion of geoengineering for discussion another day), may seem an odd ally for that effort. But with the publication of his brilliant, grandiose Modernist Cuisine, he established himself as just that.

Soup dumplings as you’ve never seen them beforeThe sustainable food movement has worked explicitly against that agenda; it has tried to re-enchant the eating experience, to restore food’s role as a cultural experience that ties us to our communities and to the Earth. Myhrvold, a Microsoft man and in fact a confirmed techno-optimist (let’s leave his promotion of geoengineering for discussion another day), may seem an odd ally for that effort. But with the publication of his brilliant, grandiose Modernist Cuisine, he established himself as just that.

Modernist Cuisine documents and pushes forward a high-art vision of food; but high art presumes the existence of other genres, too: food as popular art, food as craft. All of them place skilled human labor and ingenuity at the heart of the food project. They stand in sharp contrast to the productionist, mechanical vision of food’s future promoted by the likes of Monsanto.

As for cooking tips, I asked Myhrvold if he could offer a recipe for Grist readers. His publicist piped in that the book’s recipes were too involved to share in such a fashion, but Myhrvold offered up a simple one anyway. “Next time you’re making an omelette or scrambling some eggs,” he advised, “do this: leave out one white for every three eggs you use.” I tried it, with eggs that Alice Waters herself would approve of, from free-scratching hens that feed on grubs and kitchen scraps along with a bit of corn. The result: sublime.