Hello and welcome to week three of State of Emergency, a limited-run newsletter about how disasters are reshaping our politics. I’m Jake Bittle.

Hurricane Michael tore across the Florida Panhandle as a Category 5 storm less than four weeks before the pivotal 2018 midterm elections, killing dozens of people and destroying more than 1,000 structures. In the weeks that followed the storm, then-governor Rick Scott issued an executive order that loosened restrictions around mail-in balloting and allowed local governments to open fewer Election Day polling places.

“We do not find evidence that the amount of rainfall from the hurricane drove turnout declines. We do find that polling place closures and increased travel distances meaningfully depressed turnout.”

— Kevin Morris and Peter Miller, authors of “Authority after the Tempest: Hurricane Michael and the 2018 Elections”

A few years later, an academic study of voting in the aftermath of Michael came to a disturbing conclusion. “We do not find evidence that the amount of rainfall from the hurricane drove turnout declines” in the election, the authors wrote, but “we do find that polling place closures and increased travel distances meaningfully depressed turnout.” With each additional mile that voters had to drive, turnout rates decreased by as much as 1.1 percent. The election saw a larger share of voters in hurricane-affected counties cast their ballots by mail, but those who didn’t have time to request those ballots or vote early ended up with too few options come Election Day.

The aftermath of a disaster can be terrifying and traumatic, and many victims struggle to secure basic necessities such as food and shelter, or to fill out paperwork for disaster aid and insurance. Finding accurate information about where and how to vote is even harder — so hard, in fact, that many people who have experienced disasters don’t bother to vote at all.

The U.S. is in the midst of a historically busy hurricane season, and wildfires are breaking out across the drying West, which means there’s a high chance that many communities will see climate disasters disrupt the ordinary voting process during this year’s election. These communities may also see confusion and misinformation about which elected representatives and branches of government are in charge of which aspects of disaster response, which can make it harder to hold public officials accountable for the recovery process.

As part of our State of Emergency series, Grist, with the help of our senior manager of community engagement, Lyndsey Gilpin, is publishing two guides that will help vulnerable communities prepare for and navigate the disasters that are becoming more common. These guides are free to republish, share, and distribute.

The first guide outlines the process of disaster recovery, explaining what levels of government take charge of evacuation, aid, and rebuilding. We explain who has the power to issue emergency declarations, who handles first-responder duties during floods and fires, and who is in charge of distributing financial assistance to families and public agencies such as school boards.

The second covers how disasters can disrupt the voting process. Depending on where you live and what climate risks your community faces, one or more of the usual voting methods — mail-in voting, early voting, and Election Day voting — may be difficult or impossible. This guide covers everything from the rules and deadlines for ordering an absentee ballot in disaster-prone states to outlining what your options are if you lose access to your ID or permanent residence in the weeks before an election.

Disasters are unpredictable, but staying prepared and informed can help you and your neighbors minimize the disruptions caused by extreme weather. We at Grist hope these guides help you do that, and we encourage you to read and share them widely.

Red disaster, blue disaster

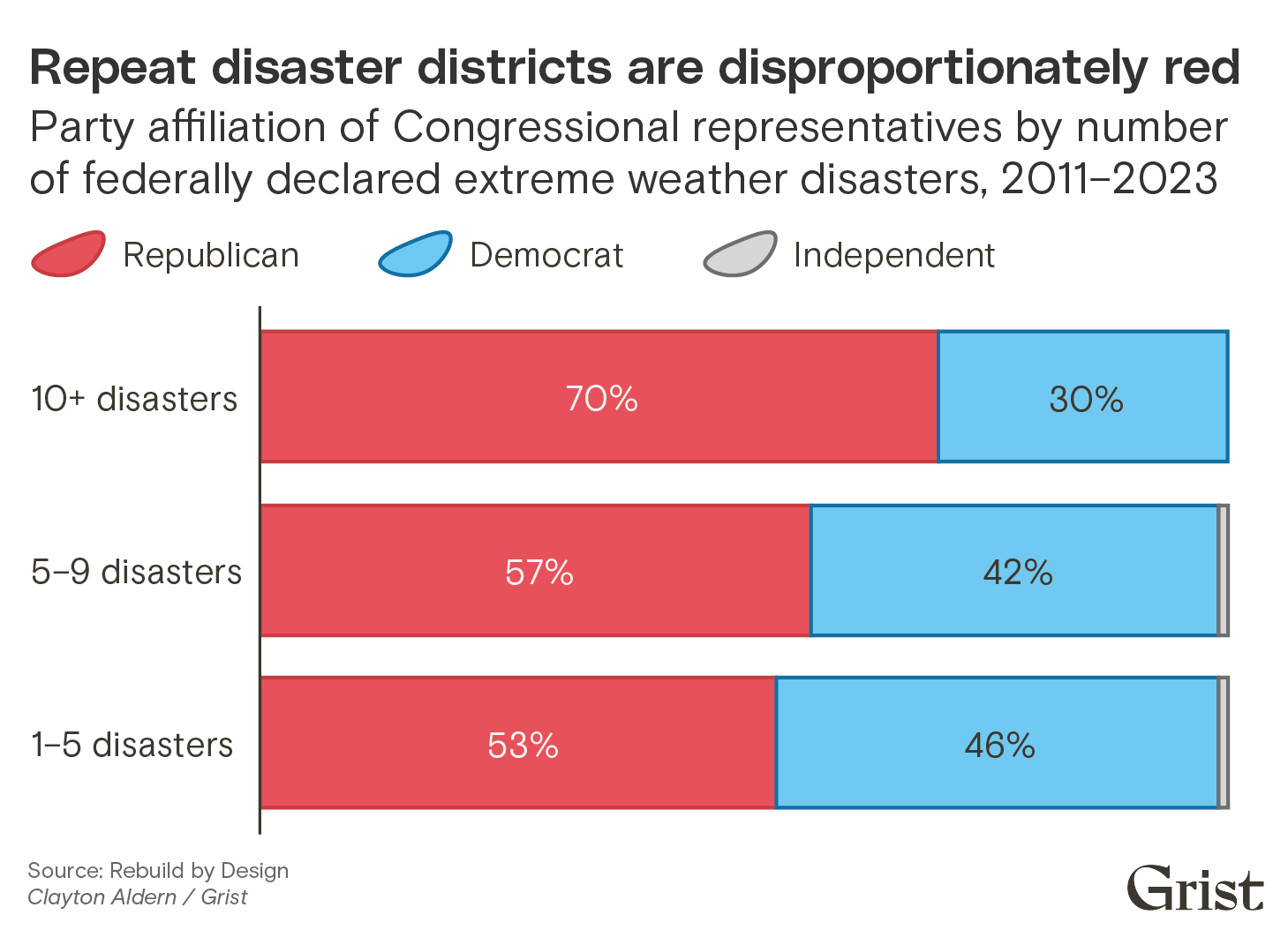

It’s a truism among emergency managers and disaster experts that no region or area is safe from disasters, but the places in the United States that have been hit hardest over the past decade are disproportionately Republican. New data from the climate resilience think tank Rebuild by Design shows that 70 percent of the congressional districts that have seen 10 or more major disasters since 2011 are under Republican control. This trend is driven largely by districts in Appalachia and the Gulf Coast.

What we’re reading

You mean it doesn’t pop balloons?: The landmark Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 was one of the single most ambitious climate laws ever passed in any country, but as my colleague Kate Yoder reports, most voters have no idea that the law has anything to do with climate change, in part because of its quite misleading name. Read more

Read more

Take a look down-ballot: The reshaped presidential election continues to dominate the news cycle, but a number of down-ballot races could be just as consequential for the climate, reports the New York Times in its Climate Forward newsletter. These include a pair of public-service commission elections in Arizona and Montana that could see utility regulators shift to focus on building out more renewable energy. Read more

Read more

Houston to vote on flood control spending: Voters in Harris County, Texas, will have their say on a property tax increase that would give $100 million to the county’s flood control district, allowing the agency to spend more money on retention ponds, flood channels, and home buyouts in the famously storm-prone city. Read more

Read more

Post-Debby anger in Florida: Residents of Sarasota, Florida, are irate after new development in their area caused worsened flooding during Hurricane Debby earlier this month. They’re looking for answers from two candidates vying for an open seat on the county commission. Read more

Read more

Maybe bring a pencil?: Michigan officials blamed stormy weather for low turnout in the state’s recent primary elections. That’s not only because storms knocked out the power grid in some towns, but also because humid weather caused ballot paper to swell, making it hard for tabulators to read ballots marked with ballpoint pens. Read more

Read more