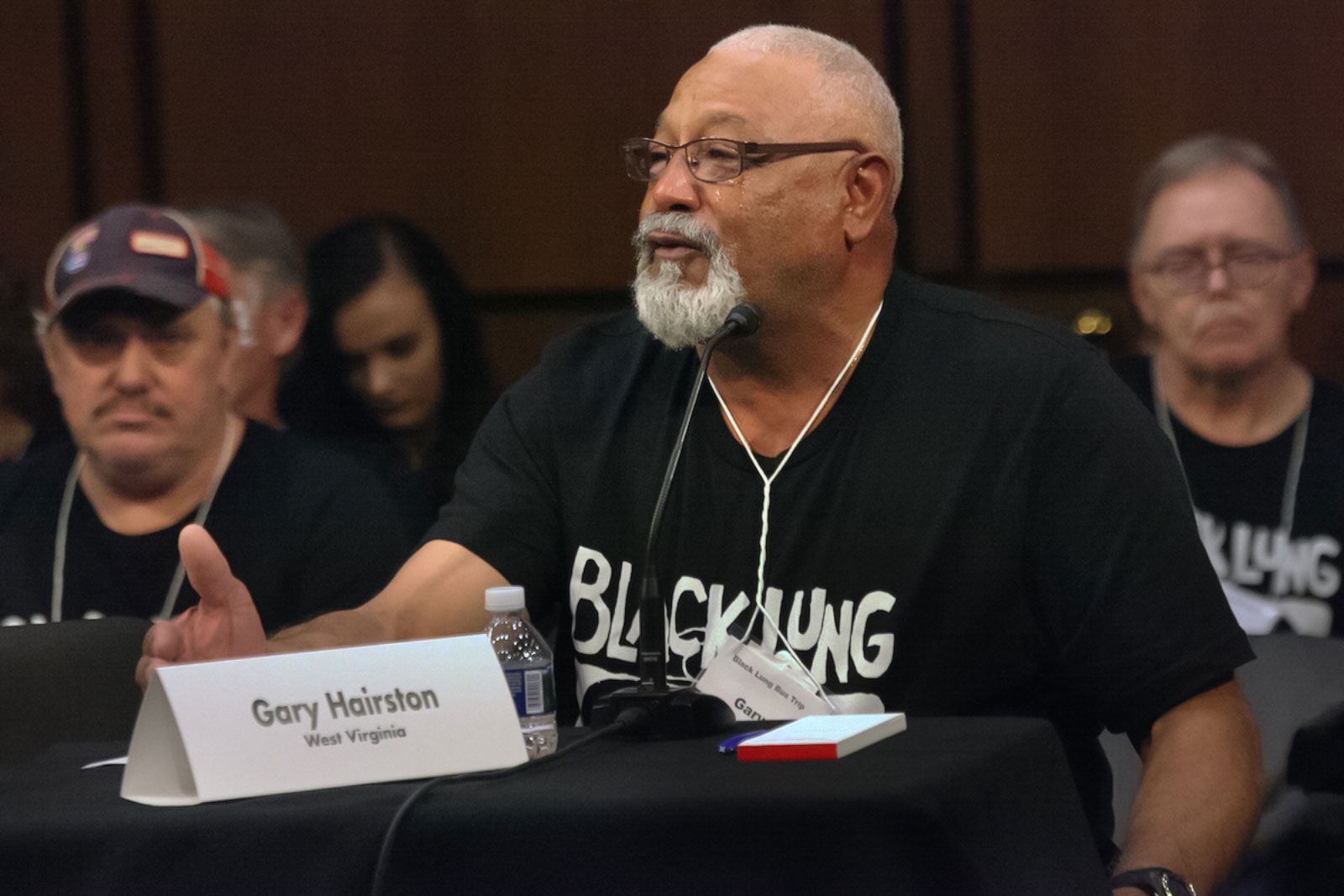

While working at a West Virginia mine, Gary Hairston dashed up a set of stairs to get out of the rain, but he only made it halfway. Doubled over and breathless, he didn’t yet know how completely his life had changed.

Hairston was eventually diagnosed with coal worker’s pneumoconiosis (CWP), commonly called black lung disease—a progressive and incurable condition caused by inhaling coal and silica dust, which causes scarring and impairs lung function.

Living with the impacts of black lung disease for the past twenty years—having to sit on the side-lines instead of playing basketball with his grandson—Hairston knows first-hand how devastating the disease can be. As the president of the National Black Lung Association, Hairston now works to help other miners secure benefits and healthcare from an increasingly vulnerable safety net.

The federal Black Lung Program was enacted in 1969, and since 1977, the Black Lung Disability Trust Fund has provided benefits when liable companies can’t be determined, or if a company goes bankrupt—an increasingly common occurrence in coal country. But in 2021, Congress failed to extend the excise tax on coal, which provides the fund’s sole source of income—jeopardizing the fund’s long term viability, and the support it offers for thousands of former miners afflicted with black lung disease.

Since its inception, the fund has been in debt to the federal treasury because so many miners needed assistance. In the past 50 years, over 79,000 miners have died of black lung disease. Today, new cases are higher than half a century ago, with the illness afflicting one in five miners in central Appalachia.

“The companies don’t want to pay, they’ve never wanted to pay,” says Rebecca Shelton, the director of policy and organizing at the Appalachian Citizens’ Law Center. The nonprofit provides free legal services to sick coal miners as they navigate what can be years-long battles to get benefits from former employers. Shelton adds, “The [companies] will fight tooth and nail to make an argument that they are not responsible for that miner’s disease.”

Many miners work for multiple companies over the course of their career, complicating efforts to hold employers liable for workers’ illnesses. Even in cases where an employer is held accountable, cases can take years and years, Shelton says. “It’s a complicated process, and it can be very drawn out.”

Without a clear clinical definition of black lung disease, miners’ claims are often challenged.

The Department of Labor reviews medical documentation, but that isn’t always a straightforward process. Miners have to prove that they have black lung disease by submitting X-rays and breathing test results that show they are actually disabled by the disease, and that it can be attributed to workplace exposure.

Hairston recounts that in his case, after submitting X-rays to the federal government, he got a call telling him to rush to the hospital because his lungs were so damaged. Yet simultaneously, a state reviewer said he wasn’t sick enough to qualify for benefits in West Virginia. Even though he had a biopsy that confirmed his illness, Hairston says that when he went to see a doctor in Charleston, “the doctor told me, said ‘Mr. Hairston, I know you got black lung, but it ain’t up to me.’”

When a miner’s benefit claim lands in court, “it’s kind of one doctor’s interpretation and testing against another’s,” Shelton says. In 2021, researchers at University of Illinois Chicago’s Mining Education and Resource Center documented that the people reviewing miners’ claims frequently had financial conflicts of interest, including coal industry affiliations.

The industry’s unwillingness to accept responsibility makes it critical to secure long term funding and enact new policies that shore up oversight. The problem is only getting worse as mine operators continue to shed liability onto the federal government. A 2020 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report found that from 2014 through 2016, bankruptcies of self-insured companies heaped an estimated $865 million of responsibility onto the Black Lung Disability Trust Fund.

The fund’s future faces an array of challenges, but ultimately, Chelsea Barnes, the legislative director of Appalachian Voices, says the path to making these crucial changes is fairly straightforward. “Congress needs to act,” she says.

In 2022, after several temporary extensions, Congress again failed to approve a long-term rate, costing the Black Lung Disability Trust Fund millions of dollars per week. The Build Back Better bill would have offered a four-year extension of the higher tax rate, but failed to move forward without the support of Senator Joe Manchin of West Virginia. “We used to go to Washington so they could see us,” Hairston says, but the pandemic made that impossible, adding, “We can’t even get [senators] on Zoom.” In May, advocates started a “We’re Counting on You, Joe” campaign, placing digital and radio ads in West Virginia to encourage Manchin to take action.

Still, new proposed policy called the Black Lung Benefits Improvement Act could help shore up protections for miners. The proposed House bill would create a legal framework to define black lung disease, help miners secure legal and medical representation, marginally increase benefits to reflect rising living expenses, and more closely regulate the bankruptcy process to prevent coal companies from shedding liability. But even if it passes, this legislation won’t alleviate the many hurdles sick miners face. The coal industry is contracting, and the fund’s revenue decreased by more than half from 2015 to 2020.

Legislation simply hasn’t kept pace with how the industry has changed. But a declining coal industry doesn’t mean a “decline in the number of people who need black lung benefits,” says Shelton.

With cases of black lung disease mysteriously increasing in recent years, a new University of Illinois Chicago (UIC) study compared historical and contemporary miners’ lung tissue and found changes in mining practices were a likely cause. As more accessible seams are exhausted, extracting coal increasingly means drilling through rock, which exposes miners to higher levels of silica dust. Their results “almost serve as a smoking gun,” says co-author Leonard Go, a research assistant professor at the UIC’s School of Public Health. As a result, younger workers are increasingly suffering from more complicated forms of the disease—needing more care, for longer.

“Silica is a lot more toxic than coal dust. That’s why in most places, silica is regulated much more tightly,” says Go. Yet even as miners are encountering silica at higher rates than other industries, they are the only workers in the country not protected by Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) silica standards, Shelton says. “There’s no way it should have taken this long,” she says. “People are dying.”

The Biden administration could choose to set new silica limits for mining that are at least in line with OSHA standards. At this point, silica’s impact is no longer a question of science, it’s a question of will. “It’s so clear what is causing this disease. Yet we can’t hold the companies that are responsible, accountable,” Barnes says.

Working in the mining industry, “it just seems like we’re a number,” Hairston says, “and once we can do nothing else for them, it just seems like they put us to the side.”

The Just Transition Fund is on a mission to create economic opportunity for the frontline communities and workers hardest hit by the transition away from coal. JTF is guided by a belief in the power of communities, supporting locally-led solutions and helping elevate the voices of transition leaders.