This post originally appeared on Energy Self-Reliant States, a resource of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance’s New Rules Project.

A proposed revision to the United Kingdom’s feed-in tariff program may have created an uproar, but it may also help spread the economic benefits of solar more widely.

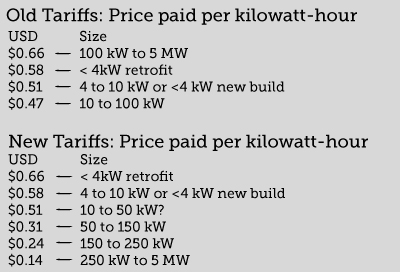

The proposed changes, announced in March, would reduce solar payments for large solar projects (50 kilowatts and larger) by 50 percent or more, but leave payments for smaller projects largely intact. The following tables illustrate:

The new tariffs will help redistribute more of the feed-in tariff (FIT) program revenue to smaller projects. The most likely manner is simply by giving less money per kilowatt-hour to the large projects, leaving more for the small projects. The following charts will illustrate.

Let’s assume that under the old FIT scheme, each project size tranche provided 25 percent of the solar photovoltaic (PV) projects under the program.

However, since a 2 megawatt project produces many more kilowatt-hours than a 3 kilowatt project, the revenues will skew heavily toward the larger projects. For the sake of simplicity, I assumed that the midpoint of each size tranche was a representative project and that they all produced the same kilowatt-hour per kilowatt of capacity.

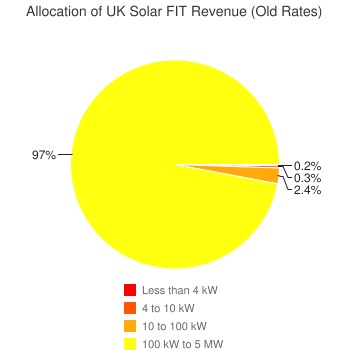

The revenue distribution can be seen in the following pie chart:

Essentially, all the FIT Program revenue was going to the largest projects. Even if three-quarters of projects were under 4 kilowatts, they would still only represent 3 percent of program revenue, with 93 percent accruing to the projects over 100 kilowatts.

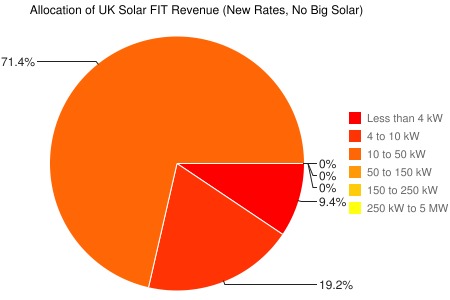

Under the new FIT scheme, the prices paid to larger solar PV projects are sharply reduced. With projects evenly distributed between the now-six size tranches, much less of the program revenue goes to large projects.

The projects under 100 kilowatts have roughly tripled their share, from 3 percent to 10 percent of revenues.

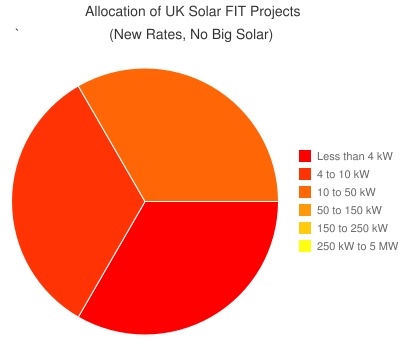

Of course, the lower prices for large solar projects could have another impact: killing large solar projects completely. Let’s assume that the new prices for projects over 50 kilowatts (that experienced the steepest revenue decline) are simply too low and that all development ceases.

The first pie chart below shows the project allocation in the FIT program without any projects over 50 kilowatts. As described, we have an even distribution (number of projects) between the smallest three size categories, and no projects 50 kilowatts or above.

The next chart shows the revenue allocation of the FIT program under this assumption. Now, nearly 30 percent of program revenue accrues to projects 10 kilowatts and smaller.

If we assume that instead of an even allocation of projects, we have an even allocation of capacity between the size tranches (e.g. 30 megawatts, 30 megawatts, 30 megawatts), then the revenues would be split evenly between the remaining size categories and two-thirds of the solar FIT program would be flowing to solar projects 10 kilowatts and smaller.

While it’s unlikely that the government plans to eliminate the large solar PV market with its price revisions, the overall effect is likely to be a transfer of program revenues to smaller projects. It may mean that the average price of a kilowatt-hour of solar is slightly higher, since there’s more room for smaller projects. The advantage in this strategy is that these revenues will be spread over a much larger number of projects and project owners, creating a larger constituency for supporting solar power and solar power policies. It will be interesting to see what happens in practice.