The warming of the planet over the past few decades has shifted a key band of clouds poleward and increased the heights of cloud tops, exacerbating Earth’s rising temperature, a new study released Monday suggests.

Bands of clouds at different latitudes.NASA

The reaction of clouds to a warming atmosphere has been one of the major sources of uncertainty in estimating exactly how much the world will heat up from the accumulation of greenhouse gases, as some changes would enhance warming, while others would counteract it.

The study, detailed Monday in the journal Nature, overcomes problems with the satellite record and shows that observations support projections from climate models. But the work is only a first step in understanding the relationship between climate change and clouds, with many uncertainties still to untangle, scientists not involved with the research said.

Cloud changes

While clouds are a key component of the climate system, helping to regulate the planet’s temperature, their small scale makes them difficult to accurately represent in climate models.

Using satellite observations to look for trends is also problematic because they come solely from weather satellites, which aren’t geared to producing consistent, long-term records. In addition, some satellites have been replaced over time, have changed orbit, or seen degradation of their sensors, introducing false trends.

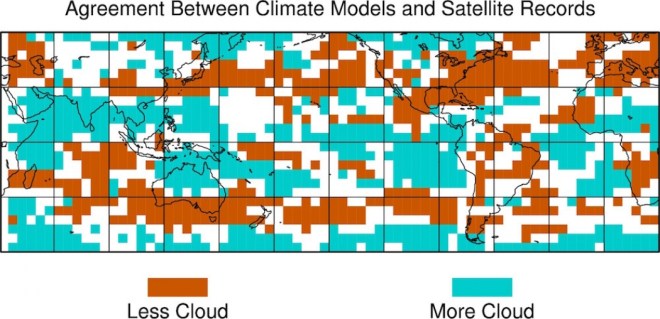

Joel Norris of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography and his colleagues had previously figured out a way to remove those artifacts in the satellite data to reveal actual trends since the early 1980s. They focused on looking for those patterns that showed up in different climate models and that our physical understanding of the atmosphere supports.

Namely, the observations showed that the main area of storm tracks in the middle latitudes of both hemispheres shifted poleward, expanding the area of dryness in the subtropics, and that the height of the highest cloud tops had increased.

Such changes reinforce global warming: There is less solar radiation at the high latitudes near the poles, so as clouds shift that way, they have less radiation to reflect back to space. High cloud tops mean that more of the radiation that is absorbed and re-emitted by Earth’s surface is trapped by the clouds (akin to the greenhouse effect).

More work to do

To investigate whether these changes in cloud patterns could be chalked up to the natural variation of the climate system, Norris and his team compared climate models that included external influences like rising greenhouse gases and volcanic eruptions with those that did not. The former showed the same trends as the observations, while the latter didn’t.

“The pattern of cloud change we see is the pattern associated with global warming,” Norris said.

Kate Marvel, a climate researcher with NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, agreed but cautioned that the cloud shifts are also consistent with what would be expected during recovery from major volcano eruptions, of which there were two at the beginning of the study period.

Locations where the majority of climate models and the majority of satellite records agree on how cloudiness changed from the 1980s to the 2000s, relative to the global mean change.Joel Norris

“More work is needed to tease out the relative roles of greenhouse gas emissions and volcanic eruptions,” she said in an email.

Norris plans to tackle this question in future work, as well estimating exactly how much clouds have changed.

The study also doesn’t deal with some of the cloud changes that are expected to be most important, namely those to low clouds in the subtropics, Bjorn Stevens, of the Max-Planck-Institute for Meteorology, said in an email. Stevens is the lead author of the chapter on clouds and aerosols in the most recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report.

Monday’s study is a step toward better understanding how clouds will change along with the climate, and lays bare the limitations of the satellite record and the need for better long-term observations, said Stevens, who was not involved with the research.

“This study reminds us how poorly prepared we are for detecting signals that might portend more extreme (both large and small) climate changes than are presently anticipated,” he said.