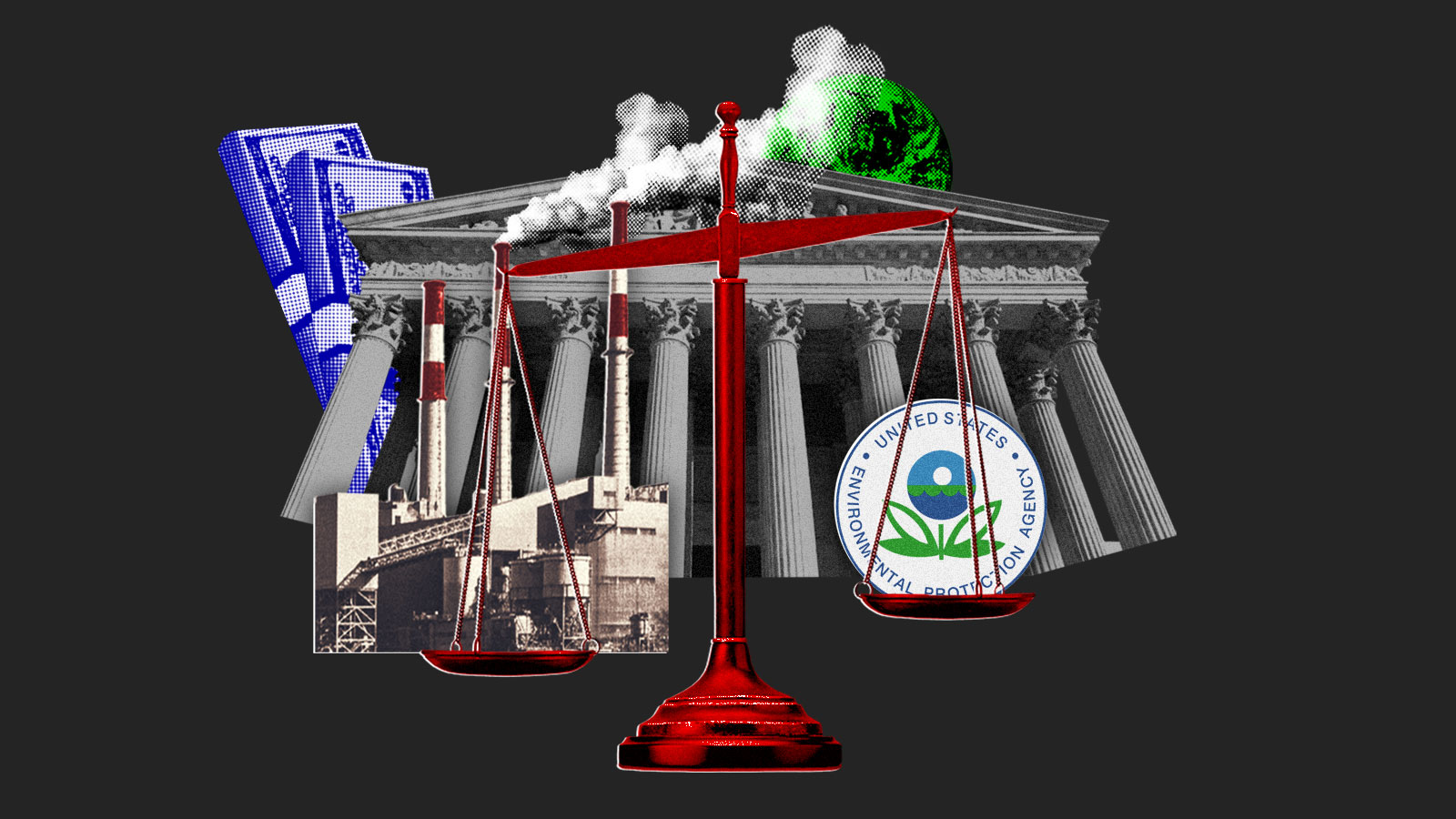

On Thursday morning, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down its long-awaited decision on West Virginia v. EPA, the case challenging the Environmental Protection Agency’s authority to regulate greenhouse gas emissions from power plants. Though the court’s six-member conservative majority moved to limit the EPA’s authority, earning the ire of environmentalists and the Biden administration alike, the court’s ruling did not deal the blow that many climate advocates expected. Ultimately, however, the decision’s use of the controversial “major questions” legal doctrine could have a chilling effect on future regulations.

Contrary to early news reports, the decision, written by Chief Justice John Roberts, does not prevent the EPA from regulating greenhouse gas emissions. Indeed, the ruling is unlikely to change the Biden administration’s approach to regulating emissions at all. In a surprising twist for a court that has seemed intent on overturning settled precedents, the ruling was narrowly framed, focusing on one reading of a single section of the Clean Air Act.

“In some ways I’m actually relieved,” said Cara Horowitz, a professor of environmental law at the University of California, Los Angeles, in a statement circulated after the ruling. “With this court we were bracing for almost anything, so this could have been worse.”

To understand West Virginia v. EPA, it helps to turn back the clock. Seven years ago, then-President Barack Obama, facing a Senate that refused to pass his landmark climate bill, unveiled a new plan to cut carbon emissions through the EPA’s executive authority. The resulting regulation became known as the Clean Power Plan, and it would have required American power plants to reduce their carbon dioxide emissions. Part of that involved “generation shifting” — ordering some utilities to generate less electricity from dirty sources like coal and more from cleaner natural gas and renewable sources.

That last component was the specific regulation disputed in Thursday’s decision. The state of West Virginia, joined by North Dakota and two coal companies, argued that the Clean Air Act, which gives the EPA sweeping authority to regulate pollutants in the atmosphere, doesn’t provide the authority necessary to require utilities to shift from one source of power to another. The EPA countered that it did have generation-shifting authority under Section 111d of the Clean Air Act, which allows the agency to mandate the “best system of emissions reductions” for existing power plants. The best system of emissions reductions, the EPA reasoned, was simply to switch to a power source that doesn’t produce as much carbon pollution.

The court ultimately sided with West Virginia. Invoking a newly-in-vogue legal doctrine known as “major questions,” Chief Justice Roberts argued that an agency cannot adopt regulations of great social and economic consequence without the clear and express approval of Congress. “A decision of such magnitude and consequence rests with Congress itself,” Roberts wrote. (In a scathing dissent endorsed by the court’s two other liberal members, Justice Elena Kagan argued that “whatever else this court may know about, it does not have a clue about how to address climate change.”)

The decision will therefore limit — but not prevent — the EPA from making future regulations around greenhouse gas emissions. According to Andres Restrepo, a senior attorney at the Sierra Club, the ruling “removes the most important tool that EPA had in its tool kit.” However, he added, “there are still plenty of avenues under the Clean Air Act to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.”

For example, the court did not overturn Section 111, meaning that the EPA will still be able to require existing power plants to use the best available technologies to cut emissions — perhaps even through carbon capture and storage. The EPA can also still regulate carbon dioxide emissions from cars and trucks, as well as methane emissions from oil and gas infrastructure. In fact, the Biden administration itself has not actually invoked the generation-shifting power of Section 111d to pursue its climate goals — and likely would not have, given the likelihood of a legal challenge similar to the one that dogged Obama’s Clean Power Plan and ultimately resulted in Thursday’s decision.

Despite the narrowness of the specific ruling, West Virginia v. EPA endorses a legal doctrine that could provide ammunition for opponents of a vast swath of government regulations in the future, hampering the executive branch’s ability to enforce regulatory laws. The major questions doctrine is both vague and powerful; in future cases, it could be used to hobble the ability of federal agencies to interpret statutes and write commonsense regulations to protect public health or the environment. In her dissent, Justice Kagan argued that “special canons like the ‘major questions doctrine’ magically appear” when it aligns with the court’s broader goals.

“Today, one of those broader goals makes itself clear: Prevent agencies from doing important work, even though that is what Congress directed,” she wrote.

One of the great ironies of the case is that the regulation at issue, the Clean Power Plan, never went into effect. When President Donald Trump came into office in 2017, he repealed the plan. But economic forces were doing the work that Obama wanted to achieve with regulation: Natural gas was getting cheap, renewables even cheaper. In 2015, the goal of the Clean Power Plan was to cut carbon dioxide emissions from the electricity sector by 32 percent by 2030, compared to 2005 levels. The country reached that goal 11 years ahead of schedule, in 2019. The U.S. Energy Information Agency published a short post commemorating that milestone. The agency also noted the cause: The country’s utilities had pursued generation-shifting after all.