Over the past several months, Joe Biden has assumed the herculean task of bringing the progressive left under his banner while maintaining the support of the more moderate liberals who form his base. As a result, he’s revisited a number of his original campaign proposals, from college debt to health care to climate.

“I was convinced that I had to move further on some things that I hadn’t focused on,” Biden told New Yorker journalist Evan Osnos in a recent interview.

During the primary contest, advocates for climate action maligned Biden’s climate platform for not being ambitious enough, despite the fact that Biden had the longest legislative environmental record of all the 2020 Democratic candidates. He was one of the first members of Congress to introduce a climate bill in 1987 and oversaw implementation of the 2009 Recovery Act, which contained $90 billion in clean energy investments.

Today, Biden’s updated climate plan is viewed as evidence of his rapid evolution on climate, even as his campaign maintains that the vice president has remained consistent in his dedication to the issue over the years. But it’s clear his team has purposefully and publicly sought input from a fair number of high-profile climate and climate justice advocates — from former rivals to Obama administration alumni, union members, and activists who actively opposed his nomination.

“That’s part of the magic of Vice President Biden,” Stef Feldman, Biden’s policy director, told Grist in a statement. “He has an unparalleled ability to bring people together to get big things done.”

“The style of putting policy teams together is a window into how a candidate will govern,” Amanda Renteria, former national political director for Hillary Clinton’s 2016 campaign, told Grist. “There is no doubt that his team and especially his policy teams feel the heavy responsibility of being prepared should he win.”

Team of rivals

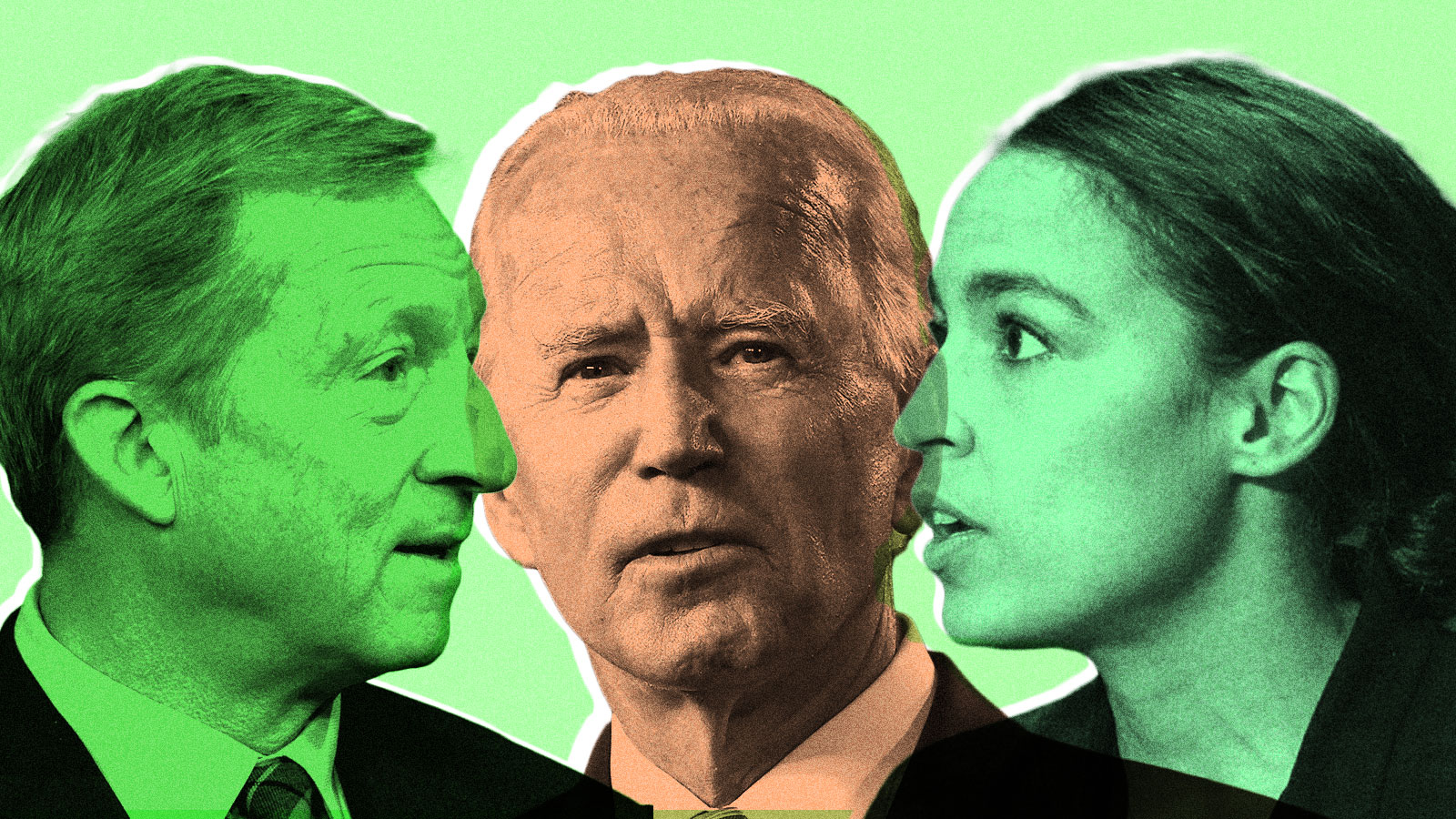

Tom Steyer has had a few careers in his life: hedge-fund manager, philanthropist, and an activist and leading voice in demanding President Donald Trump’s impeachment. The California billionaire was also a 2020 presidential candidate. His campaign, which ended in February, put climate action and environmental justice front and center.

At the fifth Democratic primary debate, in November 2019, he had a memorable exchange with the party’s current presidential nominee. Steyer proclaimed he was the only person on stage who would say that climate change was his No. 1 priority. Then he specifically called out Biden: “Vice President Biden won’t say it.”

“I don’t need a lecture from my friend,” Biden replied.

Turns out that Biden did end up needing something from his former rival. In July, the then-presumptive Democratic nominee announced the formation of a six-member Climate Engagement Advisory Council aimed at mobilizing climate-conscious voters. The council includes environmental justice advocates, the head of a labor union, the former director of the White House Office of Energy and Climate Change Policy, and a sitting member of Congress. Steyer, the council’s chairman, is harnessing the power of NextGen America, a progressive advocacy nonprofit he founded in 2013, to help accomplish the group’s goals, which include increasing youth turnout this fall.

“This council is really about connecting the vice president to different parts of the climate community, letting him hear from them and also letting them hear what I heard during the campaign, which is how much he knows and how much he cares,” Steyer told Grist.

Steyer isn’t the only one of the former Democratic primary candidates who is advising the Biden campaign. The former vice president is in regular contact with Senator Elizabeth Warren, of Massachusetts, who reportedly meets with Biden every 10 days to discuss a range of issues. When she dropped out of the race last March, she had more than a dozen different plans to address climate change — many of which drew significantly from ideas introduced by another former primary candidate, Washington Governor Jay Inslee.

Inslee, whose climate platform spanned more than 200 pages, was seen as the “climate candidate” early in the 2020 campaign season. Biden has been in touch with Inslee in recent months, and his campaign has heard from several of the governor’s former advisors, who started Evergreen Action, a climate policy and advocacy group that in April put out a set of recommendations for a green recovery from an economy ravaged by the COVID-19 pandemic.

“It seems like the campaign is trying to get information and advice wherever they can and [from] whoever can be most impactful,” said Jamal Raad, the co-founder and campaign director of Evergreen Action.

Show of unity

For Biden to successfully unite Democrats going into the general election, he had to win over the supporters of his most important former rival, Bernie Sanders. Sanders, who after two primary contests was the frontrunner in the race for the nomination, had put out a $16 trillion climate plan that he called “the Green New Deal.” It called for a 10-year mobilization to create 20 million jobs and move beyond the fossil fuel economy. He was endorsed by Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and had the support of many young climate activists.

When Sanders suspended his campaign in April, he promised to push “progressive ideas forward” with the Biden campaign and to have a strong say in the eventual Democratic Party platform. That’s why, in May, Varshini Prakash, the co-founder of the youth climate group the Sunrise Movement, got a call from a former Sanders campaign official asking her to join a new Biden-Sanders Unity Task Force on climate change. (It was one of six such task forces; other topics included criminal justice reform and education.)

“I was like, ‘Oh, my God, that is wild,’” Prakash told Grist about the invitation.

Sunrise Movement backed Sanders in the primary and had been critical of Biden’s climate platform. But Prakash agreed to be part of the task force, which would be co-chaired by Ocasio-Cortez and former Secretary of State John Kerry. It also included former Environmental Protection Agency head Gina McCarthy, who now leads the National Resources Defense Council, environmental justice advocate (and Grist 50 Fixer) Catherine Flowers, and Conor Lamb, a moderate Democratic congressman who won in a Republican western Pennsylvania district and is a natural gas proponent.

The nine members of the task force met once a week for two hours on Zoom to hash out the particulars of a set of ideas they would send the Biden campaign to influence its climate policy. “Every week, we’d submit different policy recommendations and then week by week we’d go through [the campaign’s edits], line edit by line edit, and assess each one,” Prakash said.

The task force disbanded in early July, after submitting a raft of policy recommendations to Biden’s team. A week later, Biden announced a more ambitious climate plan to spend $2 trillion over four years to simultaneously strengthen the economy and combat climate change. The plan aims to achieve an emissions-free electricity sector by 2035.

Biden’s timeline for reaching 100 percent clean electricity had been slashed by 15 years, from the original 2050. And he had also promised to spend more money on climate sooner — his initial pledge was to spend $1.7 trillion over 10 years — and ensure that 40 percent of that money goes to disadvantaged communities.

“For me, going into the task force, the goal was never to walk out with Bernie Sanders’ Green New Deal in hand,” Prakash said. “But we were able to make some pretty significant strides forward.”

A question of optics

Despite the former EPA administrators, Congressional representatives, and high-profile activists — not to mention a former secretary of state — involved in both the Climate Engagement Advisory Council and unity task force, campaign insiders say those groups have operated independently from the team that’s actually writing Biden’s climate policy. In fact, the committees’ existence might have been more for the public and the climate left than for Biden himself. That’s because, for the Democratic nominee, the optics of how he approaches climate action are almost as important as the climate policy his team puts forward.

“Coalition building and party unity is paramount,” Renteria, Clinton’s former national political director, said. She noted that “policy is rarely the key driver to winning a Presidential campaign.”

Behind the scenes, a different group, many of its members actual campaign staff, works on putting out concrete policy proposals, like Biden’s updated $2 trillion climate plan, which was in the works even before the climate unity task force was formed, according to a campaign official. The Biden campaign confirmed five names to Grist (whose identities were recently reported to be influential climate advisers by E&E News). The list includes Feldman, who, according to E&E News, worked on climate issues with Biden during the Obama administration; Cristóbal Alex, a senior campaign adviser that E&E reported is a former board member of the environmental advocacy group League of Conservation Voters; and senior advisor Symone Sanders, who worked for Bernie Sanders’ 2016 presidential campaign.

Prakash knows she’s not a campaign insider. After all, it was Sanders, not Biden, who gave her a seat at the table. But she doesn’t regret joining the unity task force. “I don’t deny that there was probably a strong part of the task force that was about this narrative of unity,” Prakash said. “I think there were parts of it that legitimately impacted Biden’s policy.”

Regardless of who Biden’s campaign puts on various committees, Prakash says there’s no guarantee that the nominee will follow through on all of the things he’s pledged to do thus far, if he wins the presidency.

“We can’t bank on Joe Biden doing anything,” she said. “It is essential that the climate movement continues to build and wield power mightily and consistently work to put pressure on people like Joe Biden.”