“We should be a little nervous,” U.S. Representative Kevin McCarthy of California said to a room full of his fellow conservatives at a political conference in Georgia last October.

McCarthy had little obvious reason to be on edge — the House minority leader was in the majority that day at the Washington Examiner’s annual political summit at Sea Island, a five-star resort. And for the first 15 minutes of his interview with Examiner reporter David Drucker, McCarthy exuded confidence. Republicans would win back the House in 2020, he promised. “The first number I want you to remember from now until the election: 19,” he said. “There’s only 19 seats for Republicans to win back the majority.”

Then the conversation turned to the subject of climate change, and McCarthy’s tone shifted.

“We’ve got to do something different than we’ve done today,” he said. The GOP’s habit of denying climate change was putting the party at risk of alienating the largest generation of American adults: millennials. “What if we show that we can solve it?” McCarthy suggested.

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky stands in front of the current House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy of California during a 2015 signing ceremony for the Keystone XL Pipeline Approval Act. MANDEL NGAN / AFP via Getty Images

If that doesn’t sound like something a Republican would say, especially to a room of staunch conservatives, that’s because it generally isn’t. For about three decades now, the party has been the enemy of climate action. The fossil fuel industry, one of the GOP’s most stalwart allies, stocks the party’s campaign coffers with contributions, and Republican policymakers can often be heard spouting denial, skepticism, and misdirection.

But a confluence of factors — in recent months, especially — have contributed to a change of heart among some Republican leaders. Intensifying hurricane and wildfire seasons have helped ground climate forecasts in reality for all Americans, including Republican voters. Polls, which have long shown strong support for climate action on the left, are starting to indicate that climate change is becoming an increasingly important issue for voters across the board. And young Republicans, the demographic McCarthy is most worried about losing, are starting to sound a lot like young Democrats on the issue.

“If President Trump wants to get my vote, he’s going to have to prioritize climate change in a way that he has not done over the past four years,” Benji Backer, the 22-year-old founder of a conservative environmental group called the American Conservation Coalition, said in a recent interview.

Another reason McCarthy felt he had to sound the alarm on climate: the Green New Deal.

In the early months of 2019, some of the same developments that were motivating Republicans to take climate change more seriously also prompted progressive Democrats to coalesce around a bold idea of how to tackle the climate crisis. The Green New Deal, which is still more of an ideological document than a raft of concrete policy proposals, offers a different approach to climate action, one that values equity and transforming the economy as much as emissions reductions. The idea is to transition the U.S. off of fossil fuels and onto renewable sources of energy while simultaneously creating jobs and revitalizing minority and low-income communities.

At first, the GOP treated the ultra-ambitious but costly Green New Deal with giddy derision — going as far as to lampoon it with a right-wing version called the Green Real Deal. The proposal, Republican thinking went, was so far-fetched it could only harm Democrats if it stayed in the political conversation. “I think it is very important for the Democrats to press forward with their Green New Deal,” President Trump tweeted last February, jonesing for a showdown. Representative Mike Simpson of Idaho called the plan “loony.” “Let’s vote on the Green New Deal!” Senator Lindsey Graham of South Carolina, who is on the record as acknowledging humans’ role in climate change, tweeted enthusiastically. The Senate did end up voting on the resolution. It was defeated 57 to 0, with the vast majority of Democrats refusing to participate in what they called political theater.

Representative Matt Gaetz of Florida speaks during a news conference to announce the “Green Real Deal,” a response to the Green New Deal, in April 2019 in Washington, D.C. Photo by Zach Gibson / Getty Images

Regardless, the Green New Deal was a hit with Americans. In July 2019, it had a higher approval rating in a survey of adults than a wealth tax, a semi-automatic assault gun ban, and free college tuition. (It polled on par with legalizing marijuana.) The unexpected popularity of the proposal forced Republicans to start coming up with a plan of their own.

“What the Green New Deal did is bring the issue of climate change to greater prominence,” Carlos Curbelo, a Republican climate hawk who lost his House seat in South Florida amid the 2018 Democratic wave, told Grist. “So it became harder for conservatives to ignore the issue.”

In the year and a half since Trump, Simpson, and Graham derided the Green New Deal, each has sought to bolster his climate bona fides. Trump has attempted to paint himself as an environmentalist (though his environmental rollbacks are deeply unpopular with swing-state voters). Last April, Simpson told a crowd in Idaho — a ruby-red state where he’s in no danger of losing this fall — that “climate change is a reality.” And Graham has publicly highlighted the daylight between himself and Trump on climate. “I would encourage the president to look long and hard at the science and find a solution,” he said.

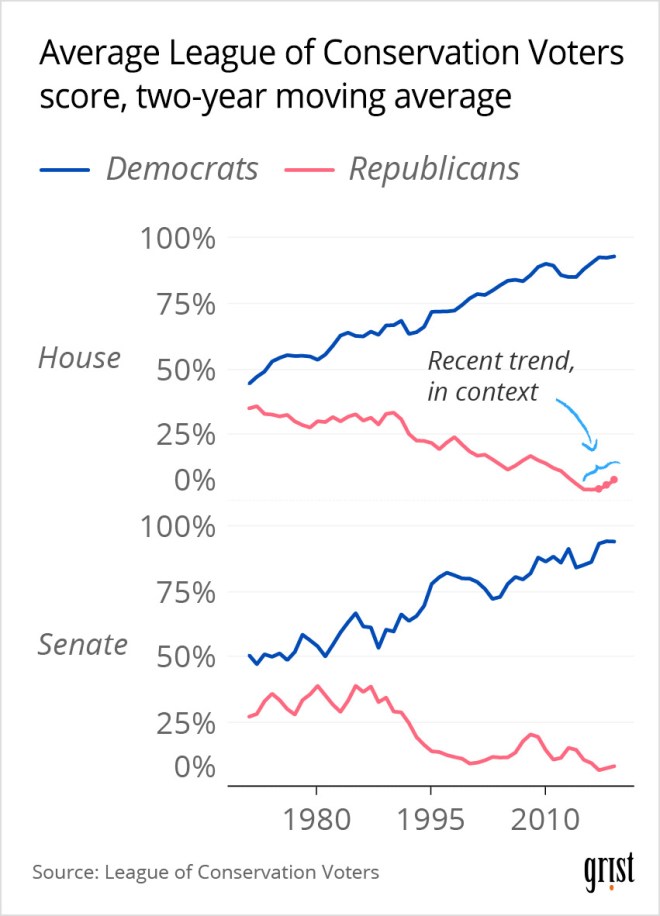

A modest improvement

The League of Conservation Voters (LCV) scores the environmental inclinations of members of Congress using their ratios of pro-environment votes to the total number of key environmental votes each year. Since 2017, House Republicans’ mean LCV score has risen from about 4.9 percent to roughly 11.1 percent. Senate Republicans have moved from 1.2 percent to 15.7 percent. That said, Republicans’ annual LCV scores are still down drastically since their senators hit their high of 46.7 percent in 1987 and House members’ combined score rose to 39.5 percent in 1990.

— Clayton Aldern

They’re not alone. A growing number of Republican politicians are suddenly talking about climate change. Some of them have even introduced climate policy. “The shift has been drastic,” Curbelo said. “A lot of it has been in rhetoric and language, but, of course, those are leading indicators that foretell what can happen in the right-of-center climate movement.”

Republicans (not all, but some) are waking up to the reality that they have something to lose by not talking about rising temperatures — perhaps more than they stand to gain by denying the existence of climate change. But there’s still a lot of distance between acknowledging that warming is happening and proposing a workable solution to the problem — or reaching a consensus with Democrats on a bipartisan path forward.

A few Republican members of Congress have the beginnings of a plan to tackle emissions. Conservative environmental groups, which have been waiting in the wings for the GOP to come around on this issue, have a pile of ambitious proposals ripe for the plucking. And with the right combination of luck, courage, and political momentum, some of those ideas could garner serious Republican support in the next Congress.

This past February, four months after McCarthy attended the conference in Georgia, the minority leader and seven of his allies in the House of Representatives — Garret Graves of Louisiana, Greg Walden of Oregon, Brad Wenstrup of Ohio, David Schweikert of Arizona, David McKinley of West Virginia, Dan Crenshaw of Texas, and Bruce Westerman of Arkansas — introduced an alternative to the Green New Deal composed of four bills.

The centerpiece of the plan is a deceptively simple proposal to plant more trees. Westerman, a former forester, introduced the Trillion Trees Act. The bill directs the U.S. to take a “leadership role” in implementing an existing World Economic Forum initiative to sequester carbon by planting one trillion trees worldwide. (On Tuesday, Trump signed an executive order that will emphasize U.S. support for the initiative by setting up an interagency council dedicated to coordinating the planting of trees domestically.) The Trillion Trees Act also promotes logging as a method of sequestering carbon. The idea is that planting new trees and cutting them down creates a loop that helps fight climate change. But that cycle has faced pushback from environmentalists, Democrats, and climate scientists who say it creates more emissions than it sequesters.

The other proposed legislation in the House Republicans’ plan would establish a carbon capture program at the Department of Energy, expand an existing tax credit for power plants that capture CO2 before it’s emitted, and promote the development and deployment of carbon capture technologies, while ensuring quicker permitting of such projects. They do not set a target date, or interim goals, for slashing emissions. In The New Republic, journalist Kate Aronoff called the plan “a package only a fossil fuel executive could love.” McCarthy says more pieces of the plan are forthcoming.

Republicans haven’t simply advanced ideas from their caucus — they’ve dabbled in bipartisanship as well. Prior to the Republican climate package’s introduction, McKinley, the representative from West Virginia, co-wrote an op-ed in USA Today with his House colleague Kurt Schrader, a Democrat from Oregon, calling climate change “the greatest environmental and energy challenge of our time.” To meet this challenge at scale, they proposed a decade of public and private investment in clean energy and infrastructure. Those investments, they said, could be followed up by new regulatory standards that ensure the U.S. reaches its targets. In their proposal, the federal government would require the use of clean technologies as they become commercially viable, and states would lead the way on setting ambitious emissions targets. It basically flips the Green New Deal’s premise — bold federal spending to combat rising emissions — on its head.

Other members of Congress have advocated for similar solutions. A pair of moderates from each side of the aisle, Republican Senator Lisa Murkowski of Alaska and Democratic Senator Joe Manchin of West Virginia, co-authored an op-ed in the Washington Post last March calling for a plan to address rising temperatures. “There is no question that climate change is real or that human activities are driving much of it,” they wrote, recommending policies that accelerate innovation in energy storage, advanced nuclear energy, and of course carbon capture.

Senators Lisa Murkowski of Alaska and Joe Manchin of West Virginia sidebar during a 2019 Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee hearing. Tom Williams / CQ Roll Call

Murkowski would later introduce a bipartisan bill with Senator Sheldon Whitehouse, a Rhode Island Democrat and long-time climate hawk, called the Blue Carbon for Our Planet Act. The proposed legislation seeks to strengthen federal research into the carbon sequestration capacity of the world’s oceans and sets targets for protecting and restoring marine resources.

It’s not the only piece of bipartisan climate legislation introduced on the Hill. The Growing Climate Solutions Act focuses on the role of agriculture in reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Senators Mike Braun of Indiana and Lindsey Graham joined two Democrats in June to sponsor the bill, which would make it simpler for farmers to sell carbon credits — generated by adopting green farming practices on their land — on existing carbon trading markets in California and in the Northeast. A motley crew of groups and corporations, including the Environmental Defense Fund, McDonald’s, and Microsoft, endorsed the proposal.

Another bipartisan effort that could meaningfully bring down emissions is the Super Pollutants Act of 2019. It would create a public-private task force with the aim of curtailing short-lived climate pollutants in the atmosphere and reducing leaks from refrigerators, air conditioners, landfills, and other sources of potent greenhouse gases. Senator Susan Collins of Maine, a Republican currently locked in a tough reelection campaign, introduced the bill last summer with Democratic Senator Chris Murphy from Connecticut. Representatives Scott Peters, a California Democrat, and Matt Gaetz, a Florida Republican and Trump loyalist, introduced companion legislation in the House.

While these proposals and the handful of other bipartisan climate-related bills introduced in the 116th Congress show a portion of GOP legislators moving beyond rhetoric on climate, none of those four initiatives — McCarthy’s raft of policies, Murkowski’s blue carbon bill, the Growing Climate Solutions Act, nor the Super Pollutants Act — has made it out of committee, let alone come to a vote in either chamber of Congress. And none of them has a higher than 4 percent chance of passing, according to the policy analytics group Skopos Labs.

Further, with scientists saying that major progress needs to be made on climate within roughly the next decade, there’s an argument that the GOP’s proposals don’t meet the moment. They certainly pale in comparison to the boldness of recent Democratic plans — further evidence that a chasm remains between the two sides on climate.

The Green New Deal may have spurred Republicans to start thinking critically about the greatest threat facing the planet, but it’s also had that effect on Democrats. The idea turned into a litmus test in the Democratic presidential primary. At least half of the 28 candidates voiced support for the proposal (and those who didn’t immediately and full-throatedly endorse it got an earful from youth climate activists). With the Green New Deal setting the terms of the climate debate within the party, candidates tried to one-up each other with increasingly aggressive climate action plans as the field narrowed over the course of 2019.

U.S. Representative Donald McEachin, a Democrat from Virginia, speaks at the June unveiling of the Climate Crisis action plan, which was put together by the House Select Committee on the Climate Crisis. Stefani Reynolds / Getty Images

The one-upmanship didn’t stop after Joe Biden was the last candidate standing. Over the summer, Democrats on the House Select Climate Crisis Committee put out a 538-page report that aims to get the country to net-zero emissions by 2050 and contains dozens of bold climate solutions (from tidal energy to indigenous forest management techniques). And as the party’s nominee, Biden updated his primary-era climate plan to reflect increasing enthusiasm among voters for bold climate action, especially in response to the economic woes brought on by the coronavirus pandemic. He says he wants to spend $2 trillion on the transition from fossil fuels to renewables if he unseats Trump in November — and in the process create millions of jobs.

The movement from Republicans over the last year or two to play catch-up came just as the other side of the aisle was moving the goal posts. Thus, the distance between the two parties hasn’t meaningfully closed. And that’s a recipe for little lasting climate policy to pass Congress and land on a president’s desk. Trump’s heedless rollbacks of what could end up being the entirety of Obama’s climate legacy is proof of the instability of a climate agenda accomplished primarily via executive order and rulemaking.

There is, however, a possible middle ground between Republicans’ natural innovation-based proposals to pare down emissions and Democrats’ plans to reshape the entire economy, but neither party currently loves it: a carbon tax.

“Almost every economist from left to right agrees it’s the first and most obvious thing to do,” said Bob Inglis, who was one of the first Republican climate hawks in the House and now runs a conservative pro–carbon tax group called RepublicEN. A carbon tax, which basically exists to make the climate costs of burning fossil fuels visible, functions like a “sin tax” on cigarettes or alcohol. It disincentivizes carbon pollution by making it more expensive upfront.

The idea should have broad bipartisan appeal. Carbon taxes drive down emissions and simultaneously generate revenue. The version Inglis’ group is pushing would either return revenue to consumers in the form of a check every year or apply it toward cutting existing taxes in other areas. A tax is a hard sell no matter what, but one that puts more money in Americans’ pockets should be palatable to the GOP. Other groups have different ideas of what to do with the money. In Washington state, a 2018 ballot measure called Initiative 1631 would have priced carbon starting at $15 per metric ton and put the money toward programs that reduce the effects of emissions and pollution in the state, specifically on marginalized communities. It seemed poised to pass but failed after oil companies poured millions into killing it.

Inglis knows just how politically dicey a carbon tax can be. He lost his 2010 House reelection bid in South Carolina in large part because he acknowledged the reality of warming and introduced a carbon-pricing bill to combat it. The pricing mechanism is as unpopular among elected Republicans today as it was in 2010. Last year, 11 Republican state senators in Oregon literally ran away from the state capitol to avoid having to vote on a measure that would have put a modest price tag on carbon emissions.

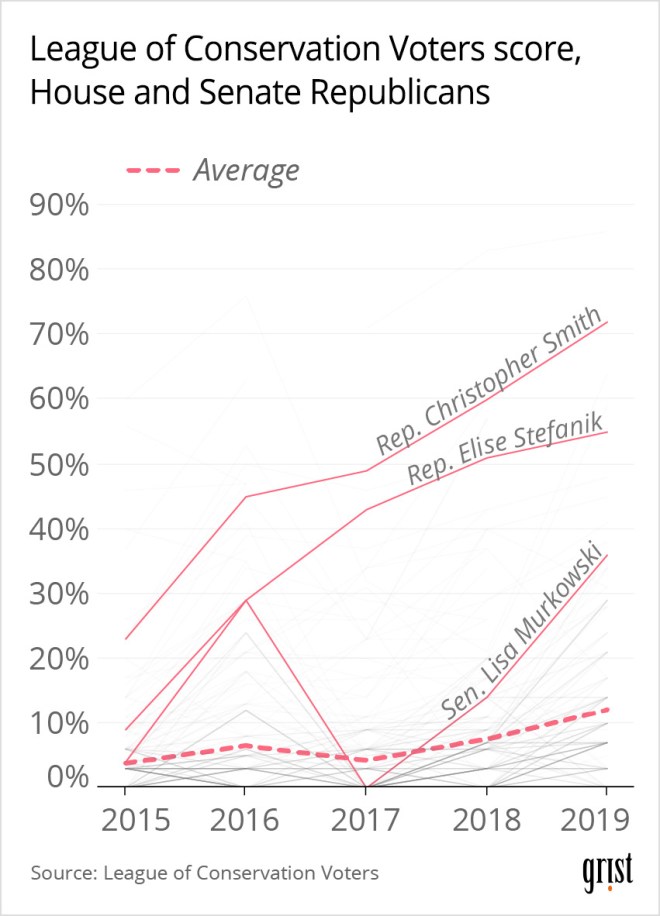

Few among many

The increase in average annual Republican League of Conservation Voters (LCV) scores stems from people like Alaska’s Lisa Murkowski in the Senate and Representatives Christopher Smith of New Jersey and Elise Stefanik of New York in the House — as opposed to a general uptick in Republican environmental sentiment. Lifetime LCV scores (as opposed to annual) for GOP legislators continue to decline.

The disconnect between annual and lifetime scores suggests any potential turning of the tide driven by a few relatively climate-friendly Republicans is wiped out by the party’s prevailing anti-environmental stance.

— Clayton Aldern

Inglis’ group isn’t the only outfit advocating for a carbon tax. The Climate Leadership Council, a think tank led by former Republican Secretaries of State James A. Baker III and George P. Shultz, advocates for a revenue-neutral carbon tax that returns the proceeds directly to Americans. Its initiative has been endorsed by Shell, ExxonMobil, and other oil companies. (If that sounds too good to be true, it’s because the plan initially gave oil companies a big break in return for their support: immunity from the wave of climate liability lawsuits sweeping the U.S. right now. The provision was later dropped from the group’s proposal.) The Citizens Climate Lobby, a formidable nonpartisan environmental group, also favors a “revenue-neutral” carbon tax, and it trains volunteers to lobby Congress on the scheme’s virtues.

Despite enthusiasm from outside groups, most GOP members in Congress won’t even entertain the idea. Brian Fitzpatrick and Francis Rooney, representatives from Pennsylvania and Florida, respectively, are the only Republicans who have signed on to any of the 10 carbon pricing initiatives introduced in Congress in the past two years. None of them have gone anywhere. Braun, the senator from Indiana who backed the Growing Climate Solutions Act, recently said he’d be open to a carbon tax, which would have been a pleasant surprise, had he not qualified it with “a year or two down the road.”

But Inglis is hopeful that the GOP will soon come around. “Things move and pendulums swing,” he said, noting that the proposals Republicans like Minority Leader McCarthy have already put forward are a promising first step in the right direction. “Incentives for clean energy, tax expenditures that encourage clean energy innovation, are like a base camp at 5,000 feet on this 15,000-foot mountain that’s called worldwide, economy-wide action on climate change,” he said. “We really need to not stop there.”

Remember back at the political conference in Georgia when McCarthy asked his audience to hold on to the number 19 — as in the 19 House seats needed to flip the chamber red? Well, Inglis is holding out for a different set of numbers: 25 House members and at least 12 senators. That’s how many Republican members of Congress he says are necessary to accomplish bipartisan climate action.

“I’d like to have a total and beautiful conversion experience from my party,” he told Grist. “But if it’s not that, it’s OK. We’ll take the 25 and the 12 to 15 and make climate action bipartisan and durable.”

It’s an optimistic vision of the future, considering Inglis is talking about a Congress that is in a perpetual state of gridlock.

Former U.S. Representative Bob Inglis receives the 2015 John F. Kennedy Profile in Courage Award for his acknowledgement of the scientific consensus on climate change — a position that cost the South Carolina Republican his seat in Congress. Paul Marotta / Getty Images

In September, the Democratic House passed a sweeping bill that would create a few of the clean energy research and development programs that many climate-conscious Republicans have been advocating for. The 900-page Clean Energy and Jobs Innovation Act would also establish more stringent building codes and energy efficiency requirements, strengthen existing weatherization programs, and promote carbon capture. It passed 220 to 185.

Seven Republicans voted in favor of the bill, while 166 voted against it. Despite being nervous about climate, McCarthy was in the nay column. Greg Walden, one of the sponsors of the four-bill Republican climate package, put out a statement criticizing the act for being unrealistic and expensive. “This bill is chock-full of government mandates that would raise what Americans pay for everything from the vehicles they drive to what they pay to heat, cool, and power their homes,” he said.

Seven House Republicans aren’t quite the 25 Inglis says are necessary to pass his bipartisanship test. But it’s not entirely impossible for Congress to achieve a consensus on protecting the environment. This summer, Congress passed the Great American Outdoors Act, which permanently allocates $900 million to the Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF) every year and puts $9.5 billion over five years toward the National Park Services’ nearly $12 billion maintenance backlog. Eighty-one Republicans in the House and 28 Republicans in the Senate voted for it.

The conservation bill passed in large part because Senator Cory Gardner of Colorado, facing a tough reelection battle this fall, took it upon himself to convert his side of the aisle to the cause. He had been trying to get the LWCF reauthorized and funded since 2015 — after all 70 percent of Colorado voters supported fully funding the LWCF — even though the leadership of his own party put pressure on him to drop the issue. Gardner refused to flip.

“There are places in our great land that can and should be enjoyed for generations to come,” he said on the Senate floor in June.

It’s not an egregious stretch of the imagination to think that, someday in the not-too-distant future, a coalition of nervous Republicans might say the same thing about the entire planet and take a stand on climate change.