On Thursday, a group of 17 Republicans did something slightly unusual for conservative Congressional representatives: They introduced a climate plan.

“Climate plan,” at least, is one way of putting it. The strategy calls for increasing domestic production of all energy sources (including fossil fuels), streamlining the permitting process for new energy projects, increasing liquefied natural gas terminals, and ramping up the mining of rare-earth minerals such as lithium in the United States. It does not contain limits on fossil fuel emissions — or other significant ways to keep global warming in check.

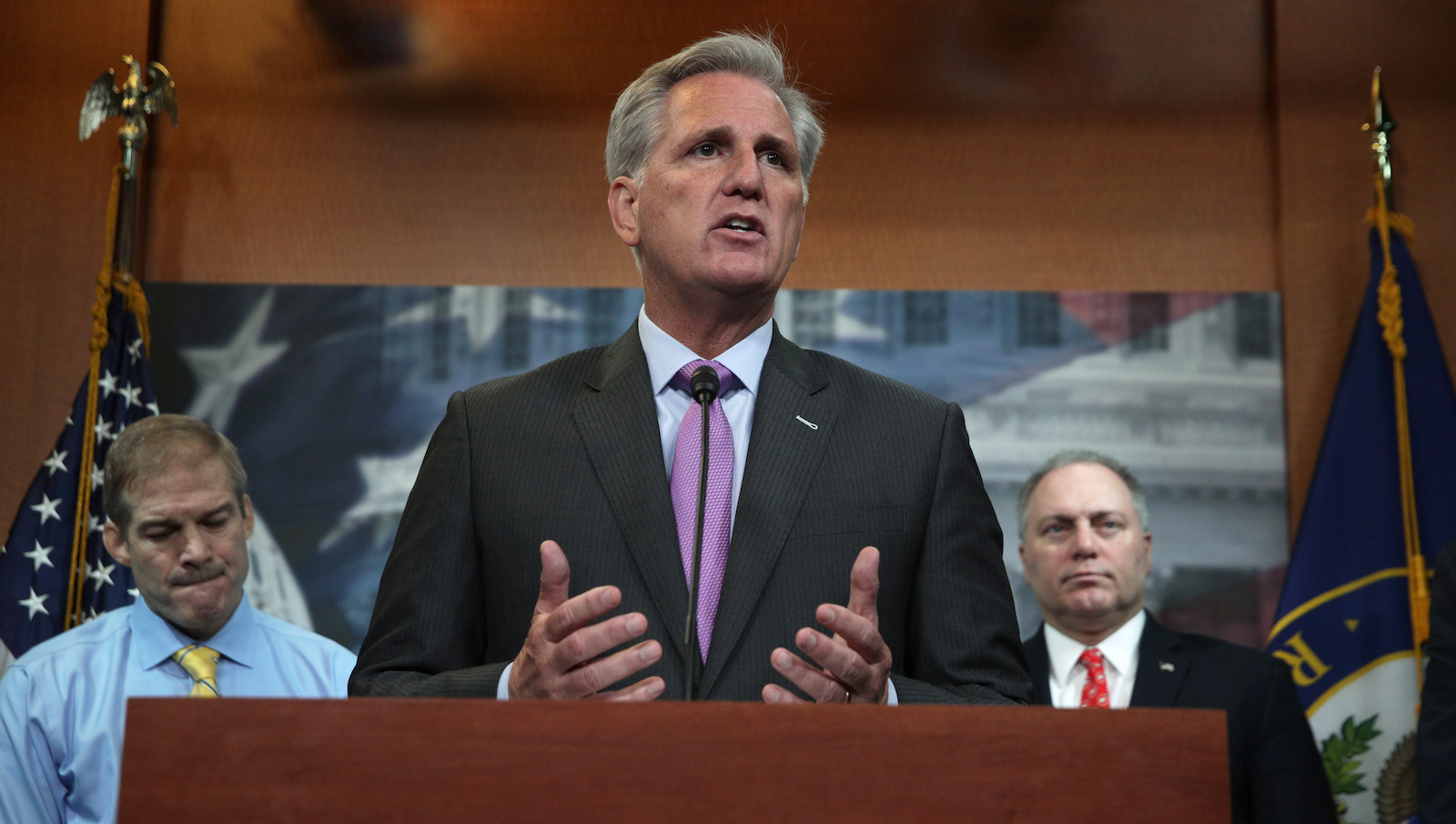

The plan is the result of an energy, climate, and conservation task force assembled by House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy last year, and is intended to serve as a roadmap for Republican action should the party take control of Congress in the midterm elections in November. Its release now is timed so that Republican representatives can campaign on the plan’s six pillars – “Unlock American Resources,” “Let America Build,” “American Innovation,” “Beat China and Russia,” “Conservation with a Purpose,” and “Build Resilient Communities.”

Research has shown that younger members of the GOP are much more concerned about climate change than their older counterparts. According to a Pew Research poll from 2020, 43 percent of millennial or Gen Z Republican voters – those between the ages of 18 to 41 – believe that climate change is having “at least some” effect on their local community, compared to only 33 percent of baby boomer Republicans, those over the age of 58. Meanwhile, 79 percent of young Republicans say the U.S. should prioritize developing alternative energy sources, like wind and solar, compared to 55 percent of boomer Republicans. And the number of groups for conservatives engaged on climate change — such as the limited-government, free-market environmental advocacy organization American Conservation Coalition — is growing in Washington, D.C.

In response, Republicans like McCarthy (who would become Speaker if Republicans take back control of the House), have begun to strategize how to attract members of their party to conservative-friendly climate plans. In February of 2020, McCarthy and several of his Congressional allies released four bills to counter progressive calls for a Green New Deal, including “The Trillion Trees Act” and legislation to support the development of carbon capture and storage.

But it’s unclear how much these Republican strategies will appeal to the truly climate-concerned. The new plan from the task force includes no emissions targets; it also lacks any limits on the use of fossil fuels, such as the once-popular carbon tax. And, according to statements that task force chair Representative Garrett Graves of Louisiana made to Politico, the task force also disapproves of clean energy tax credits that could shift the U.S. power sector toward wind, solar, and other zero-carbon sources. Graves said that sustainability could be achieved “through R&D partnering with innovators.”

The likelihood that such an “all of the above” strategy would provide significant emissions cuts is almost nil. “On its face this doesn’t appear to be a serious proposal,” Representative Don Beyer, a Democrat from Virginia, told the Washington Post. “I understand that my Republican colleagues love fossil fuel production, but it simply isn’t genuine or helpful to call that a climate change strategy.”

But with the midterms approaching — and Senate Democrats no closer to a deal on their landmark climate spending package — Republicans may just need a plan to discuss on the campaign trail.