Hundreds of Indigenous protesters and environmental advocates descended on Washington, D.C. this week to demand that President Joe Biden use his executive authority to nix new fossil fuel projects and declare a climate emergency. Every day since Monday — Indigenous Peoples’ Day — they’ve marched, chanted, and engaged in civil disobedience outside the Capitol and White House.

Now, a new report from the climate advocacy group Oil Change International adds urgency — and specificity — to their demands. According to the group’s analysis, the Biden administration has the power to stop 24 proposed oil and gas infrastructure projects that would cumulatively release more than 1.6 billion metric tons of planet-warming greenhouse gases each year. That’s equivalent to the annual emissions from 404 U.S. coal-fired power plants, or about one-fifth of the entire country’s emissions from 2019.

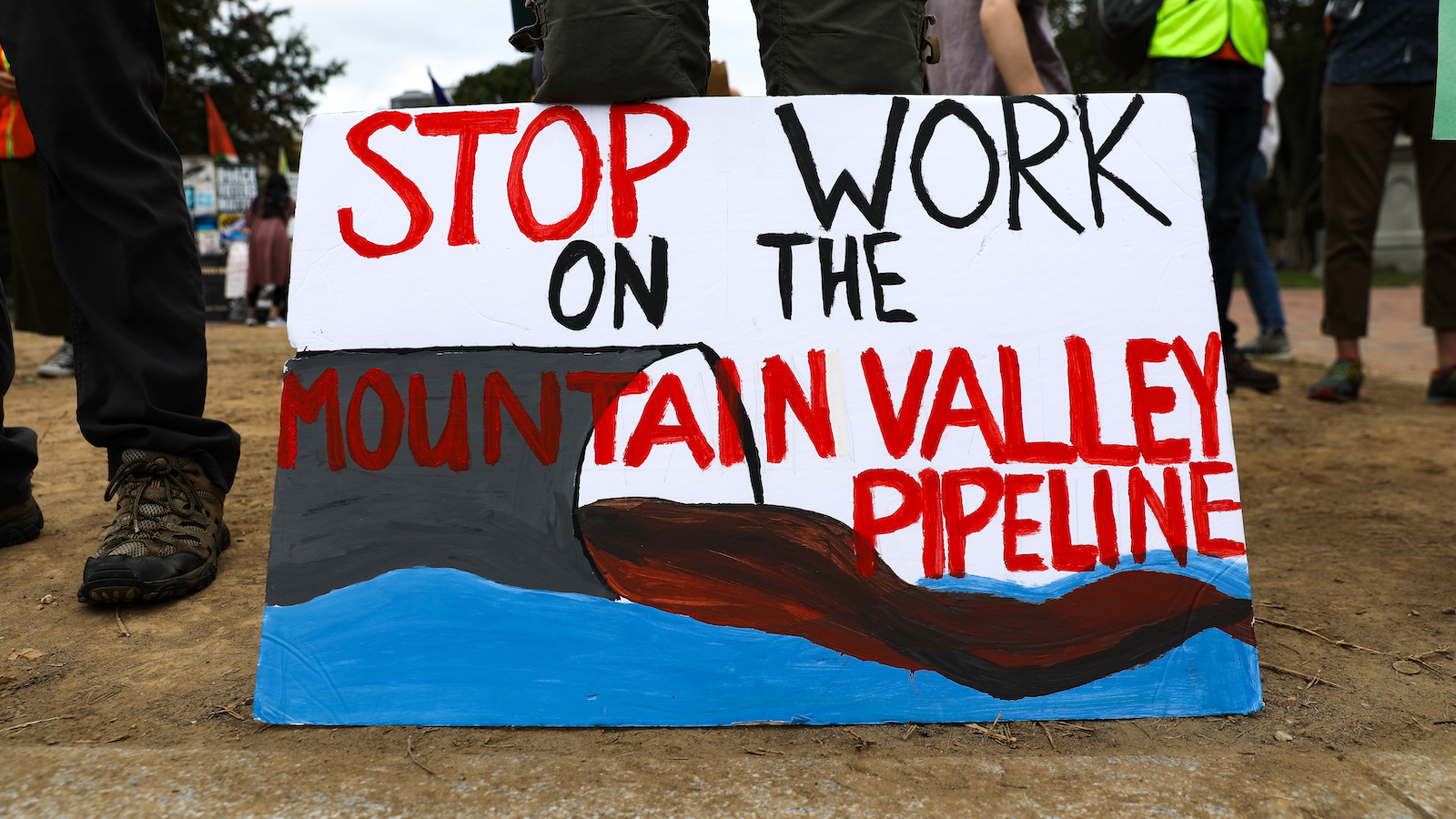

These projects include the Line 3 tar sands oil pipeline from Canada to Wisconsin, the Mountain Valley natural gas pipeline in the Virginias, and liquefied natural gas export terminals in six states. Although Biden took decisive action in January to cancel the Keystone XL pipeline, activists say he has failed to move with similar urgency on these other projects.

“Biden has had a weak delivery of the commitments that he’s made,” said Jason Crazy Bear Keck, a member of the Choctaw Peoples of Louisiana who, along with his partner Crystal Cavalier Keck, has spent more than three years fighting the Mountain Valley Pipeline in his home state of North Carolina. He visited the Capitol on Monday to deliver a speech highlighting the damage that the pipeline’s construction has caused to Indigenous communities in the region. “All of these companies are allowed to continue building even when they’ve amassed numerous violations,” he said.

The Oil Change International report looked at five proposed pipelines and 19 proposed export terminals for liquified natural gas, or LNG, for which the Biden administration could revoke or deny permits or administrative decisions. It quantified their lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions by considering the type and amount of oil or gas each project would transport, as well as the energy that would be needed to extract and process all that fuel. The researchers assumed that the oil and gas associated with each project would not otherwise be taken out of the ground, if not for those 24 infrastructure projects.

Richard Heede, a co-founder of the think tank Climate Accountability Institute who was not involved in the report, agreed with its conclusions. “The Biden Administration and agencies can (and should) not permit most if not all of the proposed projects,” he wrote in an email to Grist, especially in light of another analysis released in May by the International Energy Agency saying that no investments in new fossil fuel projects should be made if the planet is to achieve net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.

Arvind Ravikumar, a research associate professor of energy at the University of Texas at Austin, disagreed, saying the report overstated the impact associated with canceling the infrastructure projects. He said it would be more useful to think of the pipelines and export terminals within the context of a more comprehensive plan to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050 — one that could, theoretically, involve natural gas as a short-term replacement for dirtier fossil fuels like coal. He also raised a possible scenario in which stricter regulations in the U.S. — for example, to address methane leaks on gas pipelines — make LNG production cleaner than international alternatives.

According to Kyle Gracey, a senior research analyst at Oil Change International and a lead author of the report, the report provides an easy list of action items for the Biden administration following the demonstrations in D.C. “It’s a clear way to respond to the activists’ demands during the week of action,” he said. Either using executive orders or through actions by federal agencies — including the Environmental Protection Agency, the Army Corps of Engineers, and the Department of Transportation — the president’s administration has the power to prevent the fossil fuel projects from going into operation.

Economically speaking, such preemptive actions are the low-hanging fruit of climate action, compared with decommissioning fossil fuel infrastructure that has already been built. Preventing new projects from being built could help the U.S. avoid “carbon lock-in,” where pipelines and LNG export terminals continue emitting greenhouse gas for decades — throughout the duration of the infrastructure’s lifetime.

However, Gracey said, it’s still worthwhile for the Biden administration to take action to halt projects like the Line 3 pipeline, which, despite years of opposition, began transporting oil just two weeks ago. (Activists are still asking the Biden administration to suspend key permits and halt operations pending an environmental review.) Decommissioning might be costly, but better than allowing them to release millions of tons of greenhouse gas into the atmosphere.

Amanda Levin, a policy analyst for the Natural Resources Defense Council who was uninvolved with the report, also noted that it could provide policymakers with a fuller picture of oil and gas infrastructure’s lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions — both in the U.S. and abroad. If fossil fuels are destined for export — as most U.S.-produced oil and gas is — carbon accounting at the federal level often fails to take into account the emissions associated with actually burning that fuel.

“Putting it in this perspective can help the Biden administration grasp the full climate implications of expanding oil and gas domestically in the U.S.,” Levin said.

Keck, the Choctaw activist, added that he wanted to see Biden keep his word on environmental justice issues. “Do what you say you’re going to do,” he said, including by blocking the fossil fuel infrastructure projects that are poisoning his community and others. “Indigenous people always bear the brunt of the toxic fallout. They’re the first to resist and stand up for nature, even though they’re the poorest community to do so.”