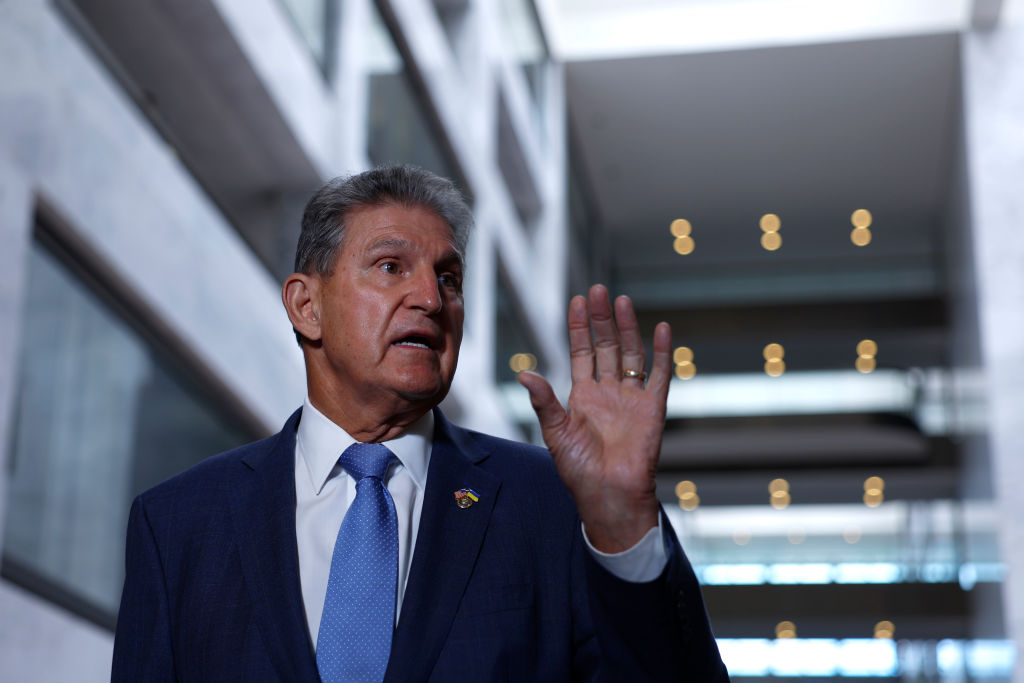

When Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer and Senator Joe Manchin announced the surprising rebirth of a deal to pass sweeping climate legislation last week, reporters could at first only speculate about what exactly it took to secure Manchin’s support.

A few days later, those questions were answered, at least partially: In exchange for a bill that is projected to reduce the country’s overall carbon emissions by roughly 41 percent compared to their 2005 high by the end of the decade, Manchin appears to have secured Democratic leadership’s support for a separate legislative effort containing a number of fossil fuel industry wishlist items. With Russia’s invasion of Ukraine fueling gas price increases, Manchin seems intent on removing bottlenecks in domestic fuel production.

A one-page summary of the hypothetical legislation obtained by the Washington Post includes provisions that cap permitting timelines for major energy projects at two years, require the president to maintain a list of 25 “high priority energy infrastructure projects,” and speed up Clean Water Act certifications. The “high priority” projects are to be selected based on their ability to reduce energy costs for consumers, promote international energy trade, and cut carbon emissions. The proposed reforms to the water quality certifications, which are often sought by pipeline companies, could make it more difficult to block such projects.

While many of these permitting reforms stand to benefit both fossil fuel producers and clean energy providers, one provision stood out for its clear benefit to a group of oil and gas companies. The summary includes a requirement to “complete the Mountain Valley Pipeline,” a 303-mile pipeline that delivers natural gas from northwestern West Virginia — Manchin’s home state — to southern Virginia.

The controversial pipeline, which has been partially constructed and is slated to carry 2 billion cubic feet of fracked gas per day, has been stymied by federal court rulings. Earlier this year, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals revoked permits granted by the U.S. Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, and Fish and Wildlife Service, requiring those agencies to reevaluate the pipeline’s environmental impact. Several other lawsuits are currently pending. The pipeline is a key priority for Manchin, who has said that the United States’ “dependence on foreign energy and supply chains from countries who hate America represents a clear and present danger and it must end.”

But whether Congressional intervention can help the pipeline cross the finish line is unclear. The one-page summary requires “relevant agencies to take all necessary actions to permit the construction and operation of the Mountain Valley pipeline” and “give the D.C. Circuit jurisdiction over any further litigation.” (A change in venue may help the pipeline developers who have been repeatedly rebuffed in the Fourth Circuit court.)

The full legislative text has not yet been released, but environmental law experts Grist spoke to said that, based on the summary, it didn’t appear that Manchin is proposing that Congress take the most sure-fire step to ease the way for the pipeline: exempting it from environmental laws. The lawsuits and the Fourth Circuit rulings have been based on arguments about the pipeline’s failure to comply with the National Environmental Policy Act and the Endangered Species Act among other laws. If Mountain Valley was suddenly exempt from those rules, its opponents would have far fewer avenues to stop it.

“From what I’m seeing, they still need to show they comply with the law even if the summary language is that it should be approved,” said Jared Margolis, an attorney with the nonprofit Center for Biological Diversity who has been involved in litigation efforts challenging the pipeline’s permits. “There’s nothing in this language that suggests to me that that Congress is directing the courts to rule in Mountain Valley’s favor in ongoing litigation.”

Congress writes laws and therefore has the authority to carve out exceptions for even the most sweeping legislation. For instance, in 2011 Congress delisted gray wolves as an endangered species, even though the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is typically responsible for adding and removing animals from the endangered species list.

“Congress could, in theory, enact legislation that exempts the Mountain Valley project from the National Environmental Policy Act and/or other environmental laws,” said Romany M. Webb, a senior fellow and associate research scholar at the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia University, in an email. In the past, Webb said Congress has sidestepped the National Environmental Policy Act by declaring a specific action “non-discretionary” or not a “major federal action significantly affecting the environment,” which is the trigger for applying the law.

But the summary of the hypothetical Schumer-Manchin legislation doesn’t indicate such an approach. Instead it directs federal agencies to move quickly to permit the pipeline, which implies that agencies will still need to follow processes mandated under environmental laws. The Fish and Wildlife Service, for instance, is currently reevaluating the impact of the pipeline on two endangered species of fish after the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals overturned a key permit earlier this year. The new legislation could direct the agency to speed up the review, but ultimately findings from the environmental analysis that the Service conducts are not under Congress’ control.

“It’s this weird in-between where they’re saying, ‘approve it,’ but they’re not exempting the [pipeline from] laws that still need to be followed,” said Margolis.

If federal agencies feel they are being pressured by Congress to rush the approval process, it could ironically further jeopardize the pipeline’s permitting prospects by leading to errors and resulting in more legal challenges, according to environmental attorneys.

“We think it would be unwise and unfair to create special exceptions to critical environmental protections,” said Ben Luckett, a senior attorney with the Appalachian Mountain Advocates, a group that has sued the federal government over its permits for the Mountain Valley Pipeline.

The legislation also gives the D.C. Court of Appeals jurisdiction over future legal challenges. That may be because the pipeline has been dealt repeated blows in the Fourth Circuit. Aside from overturning key permits from the Fish and Wildlife Service, Bureau of Land Management, and the Forest Service, the court has denied the pipeline operators’ request to assign a new three-judge panel to reconsider its permits. The legislative effort to turn jurisdiction over to the D.C. Circuit, which has a reputation for siding with federal agencies, may be one way for the pipeline developers to be heard in a more favorable venue.

The pipeline still has several other hurdles to overcome. In June, developers asked the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, which oversees permitting for interstate pipelines, to move its deadline to complete the pipeline from 2022 to 2026. They cited delays due to lawsuits and outstanding permits. The request has not yet been approved by the Commission. Lawsuits over state environmental permits from West Virginia and Virginia are also still ongoing.

News that the pipeline may be approved by Congress in exchange for climate legislation was met with apprehension from local activists who have been fighting to block the pipeline for years.

“Here in Appalachia, we refuse to be sacrificed for political gain or used as concessions to the fossil fuel industry in this so-called deal,” said Grace Tuttle of the Protect Our Water, Heritage, Rights Coalition, a group opposed to the pipeline, in a press release.