Joe Biden has said that he wants to put America “back in the business of leading the world on climate change.” On the campaign trail last year, he touted a $2 trillion clean energy recovery plan, and during his first days in office he debuted a slew of environmental executive actions. Biden has also indicated that he believes “leading the world on climate change” involves centering environmental justice — the disproportionate burden that pollution and climate change present to low-income communities and people of color.

Many of the administration’s environmental justice efforts will likely pass through Michael Regan, Biden’s nominee to head the Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA. Regan, who is currently secretary of North Carolina’s Department of Environmental Quality, or DEQ, will face questions before the Senate on Wednesday, in advance of his confirmation vote.

Regan, who is also a former EPA official for the Clinton and Bush administrations, is poised to become the first Black man to run the EPA. He’ll have his work cut out for him, inheriting an agency whose authority has been diminished by the Trump administration’s relentless regulatory rollbacks and an exodus of career staffers due to a decline in agency morale.

Regan outlasted Mary Nichols, the previous frontrunner to lead Biden’s EPA, primarily because he received more support from progressive leaders and environmental justice advocates. This support rested largely on Regan’s record at North Carolina’s DEQ, where he created the state’s first Environmental Justice and Equity Board, a community advisory body intended to give underrepresented state residents a voice in environmental law enforcement.

Advocates who worked with Regan around that effort told Grist that he changed the state’s culture around environmental justice by opening his doors to ordinary North Carolinians, regularly holding conversations with residents of communities near toxic sites, and prioritizing economic and environmental rejuvenation for areas facing high levels of pollution. For some advocates, however, Regan’s positive work was sometimes overshadowed by his apparent deference to high-polluting industries that North Carolina political leaders saw as key pillars of the state’s economy.

This balancing act is captured in a new analysis from the Environmental Data and Governance Initiative, or EDGI, a nongovernmental organization that advocates for the transparent provision of federal environmental data. EDGI’s analysis of the North Carolina DEQ’s enforcement actions, monetary penalties, and facility inspections found that Regan’s DEQ completed double the amount of inspections and levied hundreds of thousands of dollars more in penalties than his Republican predecessor. However, the number of enforcement actions, in which the department writes formal notices and administrative orders intended to actually remedy violations, remained about the same during both administrations.

“[DEQ] started doing a lot more inspections, which is really important because it’s a key way in which violations of protection laws like the Clean Water and Clean Air Act are found. But we didn’t see huge turnaround with enforcement,” said Eric Nost, an EDGI researcher and assistant professor at the University of Guelph in Canada.

Nevertheless, environmental advocates in North Carolina told Grist that Regan has been a coalition-builder who’s made participation in the state’s regulatory process more democratic.

“The first thing I have to say is that, prior to Secretary Reagan becoming the head of the Department of Environmental Quality, there was no relationship between the agency and communities in North Carolina,” said Naeema Muhammed, one of 16 inaugural members of the Environmental Justice and Equity Board that Regan started. “We didn’t get a real voice until he came into office.”

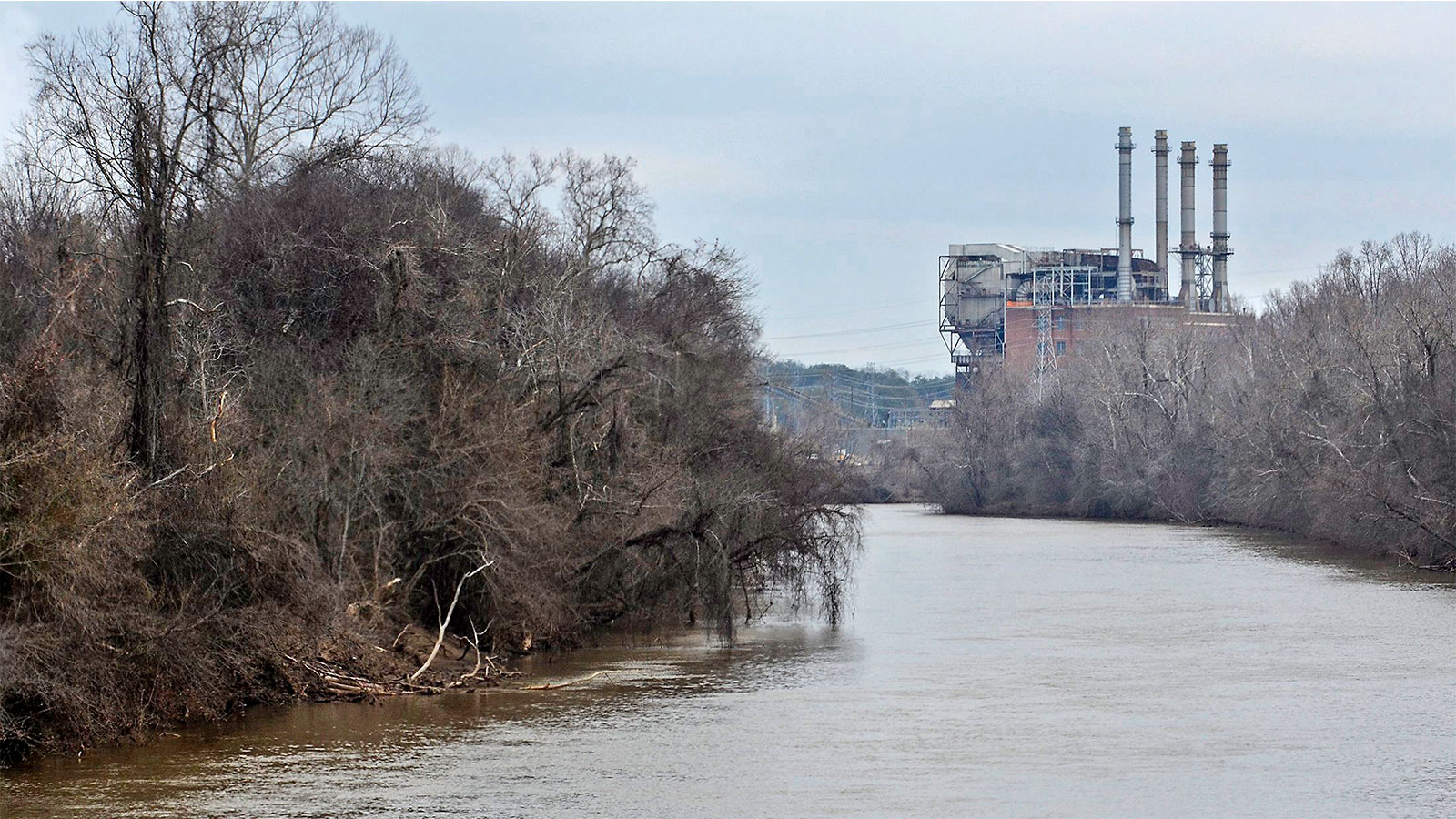

The decommissioned Duke Energy coal-fired steam station in Eden, NC, was the source of a 2014 coal ash spill. John D. Simmons / Charlotte Observer / Tribune News Service via Getty Images

Regan, whose own interest in environmental justice began after an asthma diagnosis as a child, used this community-centered approach while leading the DEQ in negotiations that resulted in the cleanup of the Cape Fear River, which had been contaminated with dangerous per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (the so-called “forever chemicals” known by the acronym PFAS). He used a similar tack to reach a settlement with the utility Duke Energy that led to the largest coal ash cleanup in the United States.

President Biden hopes to mimic Regan’s equity work on a national level by creating an environmental and climate justice division within the Justice Department to “hold corporate executives personally accountable” for exposing workers and communities to pollution. He also plans to elevate the EPA’s Environmental Justice Advisory Council, which provides advice and recommendations to the head of the EPA, to a White House entity reporting to the White House Council on Environmental Quality. That would give the council, which is composed of dozens of stakeholders from various industries, schools, and community groups, a direct relationship with the President.

Despite the DEQ’s community-centered outreach, however, Regan’s work in North Carolina also raised red flags for some advocates who claim that he sometimes favored industry over public health.

Lisa Ramsden, a Greenpeace senior climate campaigner in North Carolina, said that Regan developed a “mixed record on environmental justice issues” by failing to protect communities from the health impacts of living near hog farms, which are major polluters in the state. She also cited his approval of many operating permits for carbon-intensive wood pellet mills, which can emit harmful pollutants like particulate matter and nitrogen oxides. One 2018 study found that every wood pellet mill in North and South Carolina was located in a low-income community of color; in North Carolina the facilities are concentrated in the rural northeastern corner of the state.

“Going forward, Regan and the rest of the Biden-Harris administration need to pair their lofty rhetoric on environmental justice with consistent action,” said Ramsden. (The Biden-Harris administration did not respond to Grist’s requests for comment.)

A logging truck enters a wood pellet plant in Ahoskie, NC. Joby Warrick / The Washington Post via Getty Images

Elizabeth Haddix, a managing attorney at the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, concurred with Ramsden. She faulted Regan for renewing permits allowing hog farms to use older manure management systems that often lead to liquefied manure flowing over into nearby waterways.

Haddix was a lead attorney in a lawsuit against Regan’s DEQ, alleging that the state’s general permitting process for hog farms disproportionately burdened communities of color, which are more likely to be concentrated around the farms. The settlement required that the DEQ implement at least one year of ambient air quality and surface water monitoring in and around Duplin County, the region most heavily affected by pollution from swine waste. It also mandated that the DEQ publish an annual report with data from hog farm activity about the number of community complaints, DEQ investigations, and resolutions or fines levied.

The day after the lawsuit was settled, Regan announced the formation of the Environmental Justice and Equity Board, marking the start of a more community-centered approach to the agency’s work, in some advocates’ eyes. Nevertheless, the permits allowing hog farmers to continue using older and more polluting waste management systems continued.

“When we asked his agency to deny permits to facilities using this system, which were located in communities that are predominantly people of color, he told us that he couldn’t,” Haddix told Grist.

Instead of canceling permits, Regan has fined several farms for hundreds of thousands of dollars cumulatively for pollution in the year since the lawsuit concluded. Though he recently dropped a $90,000 fine on a polluting hog farm — the biggest fine for a North Carolina hog farm since 2012 — hog industry representatives publicly applauded Regan’s nomination to head the EPA and thanked him for supporting the industry.

“We look forward to working with him on issues of importance to U.S. pork producers, as we continue to produce the highest-quality, most affordable, and nutritious protein in the world,” said National Pork Producers Council President Howard Roth in a public statement.

Haddix believes that Regan’s friendly relationship with hog farmers was a result of their economic importance to the state: The industry employs nearly 20,000 people. She hopes he’ll “stand in his boots and take the courageous positions” in his new position.

Muhammed agreed, and she emphasized that the fight for environmental justice in North Carolina began before Regan and will continue after he’s gone.

“We’re still having meetings with [DEQ] about permits where they are not considering the cumulative impact, as well as the disproportionate impact on environmental justice communities,” she said. “We just have to get them to understand that enough is enough. If somebody already owns five toxic sites, why do they need a sixth?”

Overall, Muhammed is pleased with Regan’s transformation of the DEQ and is excited to see equity and justice being valued by national leaders.

“There’s got to be some teeth to the leadership and changemakers over at the EPA for them to be able to make the decisions that we’ll need to protect the people and environment in this country,” she added. “[Regan] is well-able to do the job, and we in North Carolina are excited for him.”