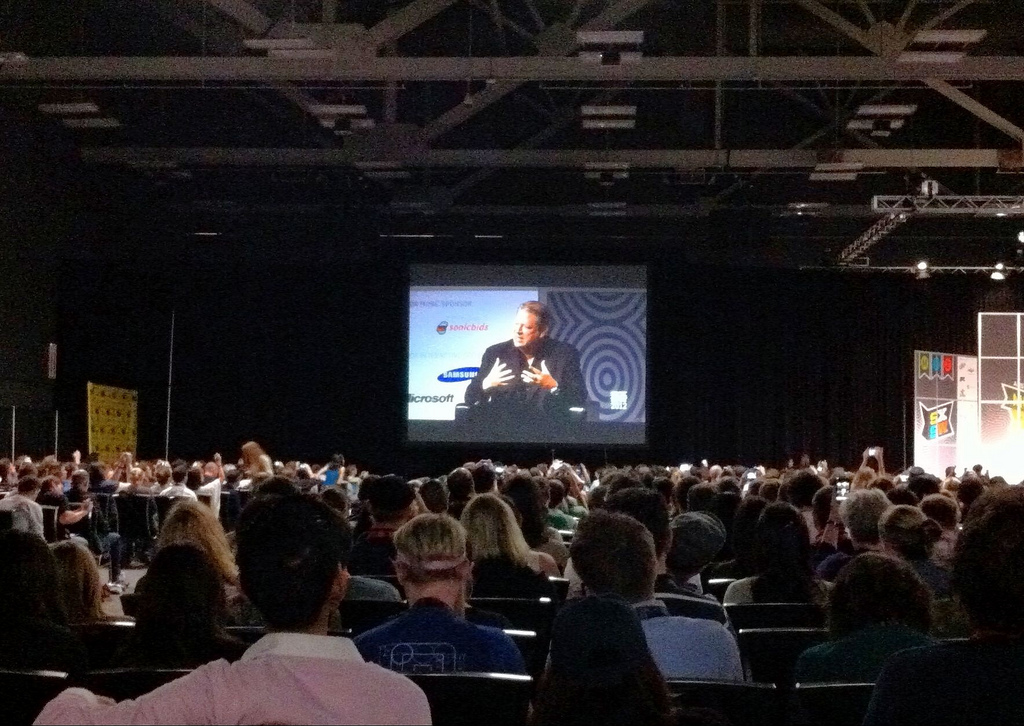

“Our democracy has been hacked,” Al Gore told a packed house at the South by Southwest (SXSW) Interactive Festival in Austin, Texas, Monday night. “It’s not working the way it should.”

“Our democracy has been hacked,” Al Gore told a packed house at the South by Southwest (SXSW) Interactive Festival in Austin, Texas, Monday night. “It’s not working the way it should.”

It was an odd image to choose in front of this crowd, which is more likely to think “hacker” means heroic tinkerer than digital thief. Indeed, by the end of the evening, Gore’s partner on stage — Napster cofounder and Facebook billionaire Sean Parker — was sounding a rallying cry for “hackers, engineers and progressive thinkers” to take back the U.S.A. from moneyed interests that are subverting democracy.

So let’s just say this was not an event with a finely tuned message.

Gore hadn’t taken the stage at SXSW to rally the crowd for a climate-change fix. His climate pitch came as an almost comically understated aside: “By the way, I need your help to solve the climate crisis. That’s another story, but I wanted to get that in there.”

Instead, Gore had come to urge the festival’s assembled entrepreneurs and geeks to help retool the financial structure of politics, so that elected officials didn’t have to spend all their time “begging on their knees” for dollars from rich contributors in order to pay for TV ads.

This is hardly a new message. But in the era of the “corporations-are-people” Citizens United decision and super PACs, it’s more relevant than ever.

How can we change things? Gore is placing his bets on the internet. (And before you make the obligatory joke about Gore having claimed to invent the internet, remember that it wasn’t true in 2000 and it’s not true today.)

“For all the optimism about the internet, we still live in the age of television,” he said. “All the news shows and debates are sponsored by coal and oil and natural gas and banks and pharmaceutical companies. And public interest movements have a hard time being heard. The internet can change that, but it has not yet. I would like to see a new movement called Occupy Democracy where people who are internet-savvy remedy this situation.”

That would be people like Parker. In person, the social-media entrepreneur comes off as far nerdier and more self-aware aware than his celebrated on-screen portrait by Justin Timberlake in The Social Network, which presented him as a dissipated, Machiavellian cokehead.

Parker — who followed his roles at Napster and Facebook by founding Causes, a “platform for activism and philanthropy” — recently led a round of investment in startup Votizen, which has collected data about 800,000 significant public offices in the U.S. and built a database of voters to help them mobilize their social networks.

In other words, Votizen will help you find out which city council candidate you actually want to support — and then give you tools to make that support matter. It’s a great idea in principle, though the organization will still have to find a way to get people to care about all the little elections in their communities.

Both Gore and Parker place their faith in the internet and social media to change the game — but their visions of how this will happen are actually quite different. For Gore, it’s just a matter of “using this magnificent set of digital tools … to elevate the role of reason and truth.” Parker, by contrast, envisions doing to politics what he helped do to the music business: disrupting the market by draining its money.

Gore’s faith in the power of reason is admirable but perhaps overly optimistic. For instance, he argued that, if social media had been more mature in 2003 when the Bush administration spread the big lie that Saddam Hussein was involved with 9/11, we might have been able to “counter” the “hogwash.” I’m not so sure: After all, though we didn’t have Facebook and Twitter then, we had a nascent political blogosphere and a healthy progressive online community. They used digital tools to try to counter propaganda and lapdog journalism, and it made little difference. Today the jury’s still out on whether the internet will do a better job of spitting out hogwash than previous media.

Parker’s approach is more structural — and more radical. “The internet,” he said, “is incredibly good at taking money out of old, slow-moving, incumbent industries. This was obviously a big part of my past at Napster.” Just as music went from $48 billion industry a decade ago to an $8 billion to $12 billion industry today, Parker says, the political system’s inefficiencies and bloated cost structures can be eliminated: “My hope is that the internet can do for the political process what it did for the copyright industries.”

Towards the end his rhetoric turned practically insurrectional: “We need to put our heads together and seize control over this system quickly, stealthily before the incumbent players wake up to what is happening, and put a bunch of progressive, forward-thinking, reason-based, rational reformers in place. And we will have a moment of opportunity, if we do this successfully, to reform the system.”

So how serious is this revolution? I don’t know about the “Occupy Democracy” label; both Gore, who is now a partner in the bluest of Silicon Valley’s blue chip venture capital firms, and Parker, who made gazillions from Facebook, are 1%-ers by bank balance, if not by ideology. The conference they addressed had already made headlines thanks to a hapless marketing scheme to turn homeless people into wireless hot-spots, which was more Marie Antoinette than Dorothy Day.

But recent examples on both right and left — from the Tea Party election of 2010 to the Keystone pipeline fight, the SOPA/PIPA protests and the Komen Foundation’s Planned Parenthood controversy — suggest that we’re indeed entering a new era of internet-fueled mass politics. Parker called it “a Nerd Spring.” Maybe we’ve only just begun to hack our democracy.