This story originally appeared in High Country News and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

On July 13, in Grand Junction, Colorado, a day after the coronavirus pandemic hit a local three-month peak, 45 elderly women flouted the state’s “safer-at-home” directive and withstood temperatures that reached 105 degrees Fahrenheit to meet at the Grand Vista Hotel for the Mesa County Republican Women’s Luncheon.

Officially, the event was meant to spotlight an issue on this year’s ballot in Colorado, a contentious measure on wolf reintroduction in the state. But as the women milled about the hotel’s conference room, discarding their masks and embracing each other, the scene looked more like a reunion. Although the group, which was founded in 1944, typically gathers monthly in Grand Junction, Mesa County’s largest city, the meetings had been on forced hiatus since March, and the women were excited to be together, excited by their shared disobedience.

The featured speaker was Denny Behrens, co-chair of the Colorado Stop the Wolf Coalition, but the true star of the day was Lauren Boebert, a feisty MAGA Republican who had just beaten a longtime incumbent, Representative Scott Tipton, in the Republican primary. Boebert moved from table to table for introductions, handshakes and hugs, a sidearm holstered at her hip. At 33, she was the youngest there by decades. In Rifle, Colorado, where she has lived since the early 2000s, Boebert owns the Shooters Grill, where waitresses in tight flannel shirts and denim serve burgers and steaks with loaded handguns strapped to their hips or thighs. The Grill was shut down in May for repeatedly violating public health orders restricting in-person dining, but the publicity Boebert received from the conflict — and a GoFundMe petition for the Grill that raised thousands of dollars — assisted her bid for Congress.

After a lunch of barbecued chicken, potato salad, and corn muffins, the group’s president officially began the meeting. She recited a prayer, quoted Abraham Lincoln, and led the room in the Pledge of Allegiance. Then she introduced key people in the room: candidates for the county commission, a representative from President Donald Trump’s Mesa County campaign office, and Boebert.

A Trump flag flies alongside an American flag in Grand Junction, Colorado. George Frey / Getty Images

Speaking to the room, Boebert described a conversation she had had with Trump, who called her after she won. “President Trump said that he was watching this from the very beginning,” Boebert said. “He said, ‘I knew that something big was going to happen with you, and now I get to call and congratulate you.’ He said, ‘Every day I’m fighting these maniacs, but now I have you to fight them with me.’”

Her audience laughed and applauded. Boebert smiled brightly. “We are going to win this fight against the liberal socialist agenda and restore the potential for our community to develop our rich natural resources right here in the ground in Mesa County,” she said.

“We are going to win this fight against the liberal socialist agenda and restore the potential for our community to develop our rich natural resources right here in the ground in Mesa County.”

Boebert is partly right; this election could mean a change in how much fossil fuels are extracted from public lands. Currently, a quarter of the crude oil produced in the United States comes from federal lands, and almost three-quarters of Mesa County is federally owned. Public land also accounts for 20 percent of the country’s total greenhouse gas emissions, making it key to any national energy (or climate) policy.

If he wins in November, Trump promises to further his agenda of “energy dominance,” which has already opened millions of acres of federal land across the Western United States to energy extraction. But if his opponent, Joseph Biden, wins the presidency, he’ll bring with him the most progressive environmental platform ever proposed by a major party candidate. And, as with so many issues in this election, the stakes are high for communities that rely on public lands — and nowhere are these themes more amplified than in Grand Junction, home of the new Bureau of Land Management headquarters.

There are 1,260 oil well sites scattered throughout Mesa County. The scene is not apocalyptic; the sites don’t dominate the landscape, and the machinery is tucked away from highways and out of view from the city center. In the rural communities that orbit Grand Junction, pumping jacks, compressors, and pipes sit amid a mosaic of farms and ranchland, orchards, and winery towns, and numerous biking and hiking trails.

Some 63,000 people live in Grand Junction, more than 80 percent of them white, and around 15 percent Latino. The city is named for its location at the junction of the Gunnison and Colorado rivers, and has a long history of mining, including uranium. In the 1970s, thousands of homeowners were warned that their homes had been built on non-remediated radioactive sites, marked by gray, sand-like waste from a defunct uranium mill downtown.

Over the last decade, Grand Junction has developed a reputation for outdoor recreation and wineries. It is a city defined by two distinct identities: new liberal-leaning outdoor enthusiasts and a more rooted, conservative population. The different groups coexist amid the expansive public land with all its multiple uses: hunting, fishing, hiking, mountain biking, motorized off-roading and skiing, as well as ranching and the extraction of oil, gas, and coal.

Stand up paddle boarders enjoy an early evening session at James M. Robb Colorado River State Park in Grand Junction, Colorado. Helen H. Richardson / The Denver Post via Getty Images

There are nearly 20 outdoor gear stores in the downtown vicinity alone, reflecting the myriad approaches to life here. Brochures, maps, and pamphlets at places like Hill People Gear — a family-run institution that sells hand-sewn goods and promotes gun rights on its website — and Loki Outdoor gear — where an 18-year-old sales associate told me she was “definitely” voting for Biden — tout the many nearby places where one might recreate. About 73 percent of Mesa County is public land, but only 18 percent of it is protected from natural resource development. So far, Grand Junction has had enough room for a variety of perspectives and competing interests. Since Trump took office, however, he has offered more land for oil and gas development in his first two years as president than President Barack Obama did in his entire second term, auctioning off more than 24 million acres of public lands. If Trump is reelected and continues to lease land at the rate of the last few years, opponents fear that land that could be managed for recreation, wildlife, or conservation will wind up under the control of energy companies. At best, it will remain idle, but inaccessible to the public. At worst, it will be immediately developed and directly contribute to greenhouse emissions in a world that is already nearing the critical threshold for the climate crisis.

Even as Grand Junction has changed, the Trump years have widened the political and cultural divide between liberals and conservatives here. Multiple use and the concept of space for all have given way to sharpened political ideologies and divisiveness, and attitudes have hardened around the pandemic and its restrictions, while protests have arisen about police brutality.

After I left the Republican Women’s Luncheon, I drove west to the trailhead of Lunch Loops, a popular mountain biking trail network just outside Colorado National Monument. I was there to meet Sarah Shrader and Scott Braden, two of the town’s most prominent conservationists.

Shrader and Braden represent an alternate vision for Grand Junction, a future in which a sustainable economy is built around abundant access to public lands. Both are relative newcomers to the area, but they’ve invested their personal and professional lives in the Colorado canyon country.

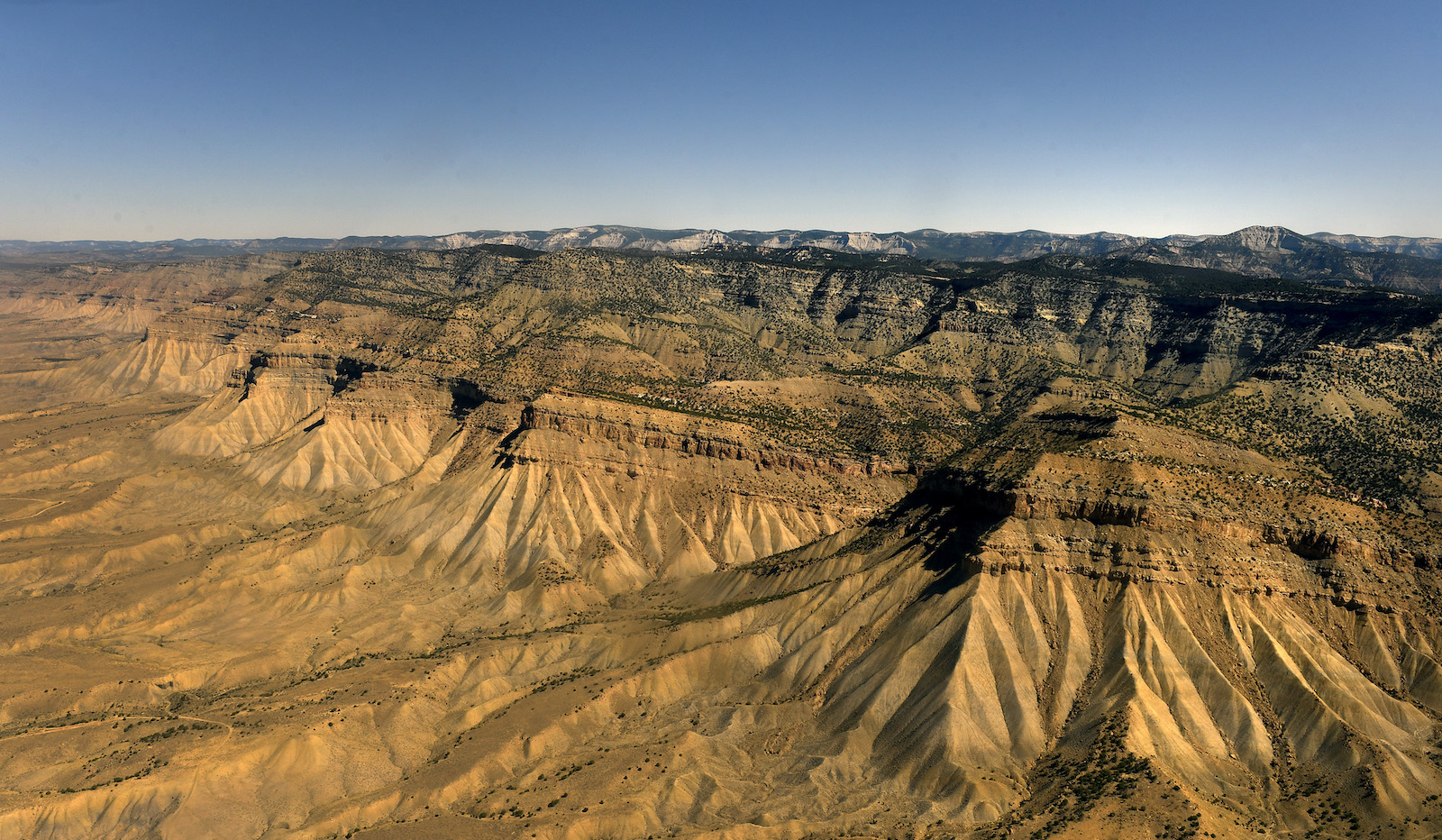

I waited for them by a picnic table in the sweltering heat. Behind me, a rocky mesa hulked over the system of single-track trails, extending out from narrow ledges and scarcely visible breaks in the canyons — the kind of landscape whose scale outflanks the mind’s ability to absorb it.

A cyclist bikes a loop through the Colorado National Monument in Grand Junction. Hyoung Chang / The Denver Post via Getty Images

The area is managed jointly by the Bureau of Land Management and the city of Grand Junction. The local BLM office, with the help of the city and a number of other land-use agencies, is extending a connector trail all the way to the monument. Once it’s finished, a person will be able to bike from the heart of downtown Junction all the way to the monument in about 25 minutes.

Soon, Braden arrived and shared some relief: iced black coffee sweetened with agave nectar, which he poured from a glass jar into a tin mug for me. Braden is 44, with a friendly smile and a dark goatee. He has worked for many conservation organizations and served a stint on a resource advisory council for the BLM. Now, he runs his own firm where he provides advocacy-for-hire for Western environmental and conservation groups.

“Grand Junction is really the perfect place to be for me,” he told me as we drank. “This is a place with an economic identity built around cattle and sheep, oil and gas, uranium mining. But you look out on places like this, and you see the ability of outdoor rec as an industry to transform it.”

Just then, Shrader drove up, parked, and walked towards us. Shrader is the head of the Outdoor Recreation Coalition, a local interest group she founded in 2015 to help outdoor recreation businesses work together to market the area as an international destination.

The three of us stood on the sandy pavement drinking our coffee, using the picnic table to reinforce social distancing. The trails were empty except for one mountain biker, who was climbing a steep ascent to the edge of the ridge; we watched, half in awe, half concerned that the rider might collapse from heat exhaustion. Shrader thought she recognized the cyclist as a pro she knew. “I was riding my bike up the monument the other day, and she lapped me going up,” Shrader said, “and she lapped me again going down.”

Shrader’s cheeks were moist with perspiration above a royal blue bandanna that she pulled down to drink her coffee. She moved from Prescott, Arizona, to Grand Junction in 2004 with her husband. In addition to running the coalition, Shrader owns a company called Bonsai Design, which builds adventure courses — hard-core mountain playgrounds with ziplines, obstacle courses, Indiana Jones-type bridges — for resorts, state parks and adventure-recreation companies. She started it in her basement in 2005, and her business grew quickly. She bought a building downtown, but outgrew that space, too. Just recently, she broke ground on a new location by the Colorado River — part of a revitalization project that features a water park designed to accommodate low-income families and encourage them to recreate on the river.

“I did that to really start talking publicly and visibly about the outdoor rec economy here and to shift focus on primarily getting our wealth from the surface of the land, instead of underneath it.”

Shrader said the Outdoor Recreation Coalition was formed to grow adventure-based industries and the higher quality of life that goes with them. “I did that to really start talking publicly and visibly about the outdoor rec economy here and to shift focus on primarily getting our wealth from the surface of the land, instead of underneath it,” she said.

Recently, the president of Colorado Mesa University asked Shrader to develop and head a new outdoor rec industry program, which offers students experience and coursework on adventure programming, guide services, and the fundamental accounting and finance classes needed to run an outdoor recreation business. This fall is its first semester. Shrader serves as the program’s director and also teaches a few classes. “It came from the demand of so many outdoor industry businesses here saying, ‘We need a talented and skilled workforce,’ ” she said. “I really created the program classes to be a reflection of what businesses need and what businesses want.”

She envisions training a new workforce for outdoor-recreation businesses in what has become an $887 billion industry — creating stable, green, good-paying jobs in fields tied to conservation and landscape preservation.

Fall colors in Mesa County, Colorado. Joe Amon / The Dever Post via Getty Images

Shrader views the coming election as a crucial moment for Grand Junction. “When we’re talking about the economy, we’re talking about creating a quality of life that is bringing people here,” she told me. “Location-neutral workers, doctors, manufacturing companies — they don’t have to work in the outdoor rec industry, but they’re coming here and raising their families here, buying houses, buying commercial property here, paying their employees here because of this” — she motioned to the rocky mesas surrounding us.

Braden and Shrader worry that Trump’s desire to develop more natural resources here could significantly alter the local landscape. “This place — along with Book Cliffs, Dolores Basin, Grand Mesa, the national monument — is the critical infrastructure of our community, if you’re thinking about creating that quality of life,” Braden said. “If an oil well and a surface oil truck is one picture of an economy future, this place would be the picture of the other economy future. We have a choice as a community, which one we want to run towards.”

As Shrader drank her iced coffee, Braden continued. “Grand Junction is an avatar for this choice,” he said. “This is a place that, not too long ago, our picture of our economic future was an oil field. Now we have a choice.”

For decades, the Bureau of Land Management has struggled to disentangle the two contradictory directives that make up its mission: management of the landscape for conservation, and a quota for sustained yield of that landscape’s natural resources. Its direction sways back and forth, reflecting the interpretation of the administration currently in charge of the agency’s mandate for multiple uses. The idea is that the political appointees who run the agency have a responsibility to take a balanced approach that keeps in mind the public land’s many resources — timber, energy, habitat, and more — and its various other uses, including recreation, mining and grazing. The BLM’s mission, in its own words, is to balance these at-odds uses “for the use and enjoyment of present and future generations.”

But ever since the BLM was formed in 1946 by President Harry Truman, to act as the guardian of the public lands, it has served as more of a purveyor than a preserver of land, water, and minerals. It was established to administer grazing and mineral rights, and it largely benefited ranching interests, officially combining the General Land Office and the U.S. Grazing Service — both of which aided in the exploitative conquest of the Western United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The agency has never found its balance. In 1996, President Bill Clinton made history by designating the 1.7 million-acre Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument in southern Utah, the first national monument to be overseen by the BLM. Then, under George W. Bush, millions of acres of public land were leased for oil and gas drilling and logging, and “Drill, baby, drill!” became a 2008 Republican campaign slogan. Obama’s tenure over Western public lands was marked by the implementation of policies meant to rein in extraction and focus on preservation. The result was a record of compromise and small gains: He delisted 29 recovered species, but weakened the Endangered Species Act; he designated over two dozen national monuments, more than any other president, but left other important public lands unprotected; he promoted tribal sovereignty, but failed to address systemic inequalities in Indian Country. And even though Obama is considered the first leader to seriously address climate change, he also oversaw surges in oil and gas production.

“As we think about climate solutions and the way that plants and animals are reacting to these really strong changes in our environment, the BLM becomes the bridge to other areas of refuge.”

Neil Kornze, who served as BLM director under Obama, told me that the agency acted as crucial connective tissue in addressing climate change. “As we think about climate solutions and the way that plants and animals are reacting to these really strong changes in our environment, the BLM becomes the bridge to other areas of refuge,” he said. “Questions about sustainable use and conservation are going to be really, really important for the next administration.”

But while the Obama administration’s policies were aimed at protecting more public lands from energy development, the rollout of those regulations was difficult for Bureau of Land Management field offices across the West. Jim Cagney, the BLM’s former Northwest district manager, based in Grand Junction, told me that the administration was too ambitious, and it overreached. Effective land management, he said, happens over decades, not over the course of a single administration.

A drilling rig in Colorado. Craig F. Walker / The Denver Post via Getty Images

“I don’t want to burst any environmentalist bubbles or anything, but those guys were really calling the shots from up above,” Cagney said. “My feeling at that time was that we can’t take on this many battles and win them. We’re going to get more pushback than we can handle. Can we slow down and bring this along at a sustainable pace? The Obama administration would have none of that.”

Cagney, who worked for the BLM for three decades, retired before Trump became president. “It’s plainly obvious that [the Trump administration’s] public lands approach is rooted in the denial of any science that conflicts with their extractive agenda,” Cagney said. “I’ve spent my lifetime trying to maintain a balanced, unbiased approach to public lands. I think both parties overplay their hand, and the ever-increasing pendulum swings associated with administration changes are making management of the public lands unaffordable and impractical.”

Since his inauguration in 2017, Trump has worked hard to undo Obama’s legacy, especially when it comes to the environment. I interviewed more than a dozen former Interior Department employees, BLM directors and staff, conservationists, environmentalists, and Washington insiders, and by most accounts, Trump has narrowed the vision of the beleaguered agency far more than any of his predecessors. “Energy dominance is not the same thing as multiple use,” Nada Culver, vice president of public lands and senior policy counsel for the National Audubon Society, told me. “It’s a very, very radical tug on the balancing act. There is a thumb on the scale.”

Back in October 2016, I attended a campaign rally for then-candidate Trump on the tarmac of the Grand Junction airport. Ten thousand people waited more than four hours outside the arena. The scene was rowdy, joyous, like an energized fan base at a music festival. Although public lands account for nearly three-quarters of the land inside Mesa County’s limits, a place known as the gateway to the canyonlands and the home of Colorado’s first national monument, Trump never mentioned them explicitly. But he knew that energy development would resonate with his constituency. “We’re going to unleash American energy, including shale, oil, natural gas, clean coal,” he told the crowd. “That means getting rid of job-killing regulations that are unnecessary. … We’re going to put the miners right here in Colorado back to work.

“We are going to dominate,” he said, as his audience whistled and whooped.

“That means getting rid of job-killing regulations that are unnecessary. … We’re going to put the miners right here in Colorado back to work. … We are going to dominate.”

Trump won Mesa County by 64 percent — 28 points more than Clinton. And so began what critics call his “frontal assault” on regulation and public lands protections, and a chaotic remaking of the Bureau of Land Management. Just one week into his presidency, in his second executive order, Trump took aim at the National Environmental Policy Act — the bedrock environmental legislation that safeguards public land and resources for future generations by requiring thorough environmental impact analyses — and ordered expedited environmental reviews for high-priority infrastructure projects. A few months later, Trump ordered public land agencies to remove regulatory burdens that blocked projects to develop the “nation’s vast energy resources,” giving agencies 45 days to review ongoing projects.

Then-Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump arriving at a rally in Grand Junction, Colorado, on October 18, 2016. David Hume Kennerly / Getty Images

According to an analysis by The New York Times, in the past few years, Trump has reversed 68 environmental rules; more than 30 similar rollbacks are currently in progress. Many of these moves impact the BLM. In April 2017, Trump signed an executive order to review all designations under the Antiquities Act; later that year, he shrank the boundaries of both Grand Staircase-Escalante and Bears Ears national monuments. In December 2017, he scrapped a rule that required mines to prove that they could reclaim their mines; a month later, he ordered Interior to expedite rural broadband projects on public lands. Trump has exempted pipelines that cross international borders, such as the Keystone XL project, from environmental review. In April 2019, he lifted an Obama-era moratorium on new coal leases on public lands; that summer, he nixed a ban on drilling in Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

Under Trump’s watch, the Interior Department has moved the Bureau of Land Management headquarters from Washington, D.C., where the agency had ready access to decision-makers and politicians, to Grand Junction. The controversial relocation has been criticized as a blatant attempt to deliberately shed institutional knowledge and talent. Since the announcement, the agency has lost half of the staff who were slated for relocation. The department defends the move, citing cost savings and claiming it will be better able to meet its mission by placing “leadership closer to the resource and lands that BLM manages.” The Government Accountability Office, however, has determined that Interior officials lied about the reasons for the move. Cagney, the former Northwest District manager, sees the relocation as a way to dismantle the agency outright — “an attempt to divide and conquer and disband the agency and remove it from the power center of decision-making,” he told me.

Trump has also refused to hire a BLM director. Instead, he selected William Perry Pendley, a controversial conservative with a history of lobbying to transfer public lands to local private interests, to serve as acting director in 2019. Trump sidestepped the nomination process altogether until this June, when he formally nominated Pendley to lead the agency in an official capacity. After months of outrage and opposition — notably from vulnerable Western politicians like Colorado’s Republican senator, Cory Gardner, who is up for reelection this year — Trump withdrew the nomination. Still, Pendley remained at the helm of BLM until a federal judge in Montana ordered Pendley to leave his post in late September. The judge concluded that Pendley served unlawfully as acting director for 424 days.

By most accounts, Trump has been successful in advancing his agenda of energy dominance. Though American energy production set records during Obama’s tenure, according to the Interior Department, the revenue from federal oil and gas output in 2019 was nearly $12 billion — double that produced during Obama’s last year in office. The courts — and the uncertain economic situation — have acted to temper abrupt change, but Trump has done everything in his power to clear the way for development.

President Donald Trump walks to the Oval Office after announcing a rollback of the National Environmental Policy Act in July. Drew Angerer / Getty Images

“Four more years of Trump means a steady stream of oil and gas lease sales and locking in leases and fossil fuel emissions when we can’t afford it,” Kate Kelly, public lands director for the Center for American Progress, an advocacy organization for progressive policies, told me. “We will continue to see every acre that could potentially be leased, leased, and the hollowing out of the agencies that are there to protect these landscapes.”

In late summer, Trump revealed one of his most extreme changes yet: Amid the widespread economic crisis due to the coronavirus pandemic, his administration finalized a “top-to-bottom overhaul” of NEPA. Trump’s change would fast-track infrastructure and result in shorter reviews and a narrower comment process, thereby limiting what the public is allowed to scrutinize. Already, 17 environmental groups have sued. “[NEPA] is a tool of democracy, a tool for the people,” Kym Hunter, a senior attorney with the Southern Environmental Law Center, the firm representing the groups, wrote in the suit. “We’re not going to stand idly by while the Trump administration eviscerates it.”

“Left unchecked, it is literally an existential threat to the planet and our very survival. That’s not up for dispute, Mr. President. When Mr. Trump thinks of climate change, the only word he can muster is ‘hoax.’ When I think about climate change, the word I think of is ‘jobs’ — green jobs and a green future.”

And Trump has promised to continue what he started if he’s reelected in November. He remains skeptical of climate change, calling the crisis a “make-believe problem,” a “big scam” and a “Chinese hoax.” In countering Trump on the issue, Biden has been able to make his most compelling argument for the presidency yet: “There’s no more consequential challenge that we must meet in the next decade than the onrushing climate crisis,” he said at a virtual town hall in July. “Left unchecked, it is literally an existential threat to the planet and our very survival. That’s not up for dispute, Mr. President. When Mr. Trump thinks of climate change, the only word he can muster is ‘hoax.’ When I think about climate change, the word I think of is ‘jobs’ — green jobs and a green future.”

Right now, and for the foreseeable future, the public lands are the battleground for the climate crisis. The United States is the world’s largest emitter of fossil fuels after China, meaning that the country must play an outsized role to curb the climate crisis. In order to keep rising temperatures within the critical 2 degrees Celsius threshold that scientists deem necessary to prevent the worst environmental impacts, the United States must decrease its total emissions by 25 percent by 2025. We are not on track to meet this benchmark, but reducing the 20 percent of emissions that occur on public lands would significantly help the nation to limit catastrophic ripple effects from the worsening crisis. The fight between Biden and Trump is really a fight over keeping fossil fuels in the ground.

In late October 2019, Joe Biden traveled to Raleigh, North Carolina, for a campaign rally. There, he encountered Lily Levin, an 18-year-old climate activist with the Sunrise Movement, an international coalition of more than 10,000 young people fighting for immediate action on climate change and skyrocketing inequality. “I’m Lily from Sunrise,” she said as Biden turned around to face her. “I’m terrified for our future. Since you’ve reversed and are now taking super PAC money — ”

Biden held up a phone, pointed it toward himself and Levin, and took a selfie, as Levin continued: “How can we trust that you’re not fighting for the people profiting off climate change?”

“Look at my record, child,” Biden responded.

“Young people simply cannot trust that politicians — who have kicked the can down the road for decades when it comes to climate change — will be on our side, unless we also know that they’re not taking a single dollar from the merchants of our planet’s destruction.”

A few days earlier, Levin had learned that Biden was walking back an earlier promise that his campaign would not accept dark money from super PACS — interest groups that influence politics without regulations to require disclosures of the identities of their donors. “This lack of transparency is a problem, because young people simply cannot trust that politicians — who have kicked the can down the road for decades when it comes to climate change — will be on our side, unless we also know that they’re not taking a single dollar from the merchants of our planet’s destruction,” Levin wrote in an op-ed for BuzzFeed News a few days after the encounter.

Biden has struggled to capture the support of the progressive arm of the Democratic constituency, and his exchange with Levin deepened the doubts of the Sunrise Movement, which, since its creation in 2017, has become an influential force in Democratic politics. The group was an early champion of the Green New Deal, which was initially mocked by politicians, including Nancy Pelosi, as being overly ambitious and impractical. By 2019, however, 16 of the Democrats running for president had endorsed it. Biden was not among them.

In the few years since its founding, the Sunrise Movement has grown from a small group of progressive young people — its oldest leader is 33 years old — to a highly visible organization that draws thousands of volunteers and members across the country. The group’s stamp of approval has become perhaps the single most important hurdle to clear for Democratic candidates, and Biden has stumbled in his efforts to achieve it.

Youth protesters, including from the Sunrise Movement, demand climate action during the Global Climate Strike in September 2019. Cory Clark / NurPhoto via Getty Images

Biden, who has been in politics for 47 years, has a checkered environmental record, as Levin likely knew, and has long been considered a moderate on energy. Throughout his years as a senator and his tenure in the Obama administration, Biden has always aimed for the middle ground on climate policies, espousing a diversified energy portfolio that keeps “bridge fuels” such as natural gas. As recently as this August, Biden assured some constituents that fracking would continue under his administration — although he has stated that he would not allow it on public lands.

When Biden released his initial climate plan in June 2019, it fell far below what youth climate activists demanded, focusing more on market-driven changes rather than federal mandates to limit emissions. It shied away from a carbon tax, for example, instead favoring policies that finance emission-cutting efforts by the private sector. That December, the Sunrise Movement gave Biden an “F” rating, deriding his plan for its lack of specificity and saying it fell far short of promises made by other presidential candidates, such as Senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren. Polls from the time showed that Biden lost more than three-quarters of voters younger than 45. “We don’t have to beat around the bush,” one Sunrise member said. “Young people ain’t voting for Joe Biden.”

But in the months following the primaries, Biden abandoned his moderation in favor of a bolder, more progressive climate stance, largely as a result of pressure from the Sunrise Movement. In late July, Biden released a radically progressive, $2 trillion climate plan, the most ambitious blueprint ever released by a major party nominee and the culmination of months of collaborating with members of the Sunrise Movement.

Just days after releasing his plan, Biden held a virtual fundraiser. “I want young climate activists, young people everywhere, to know: I see you,” he said. “I hear you. I understand the urgency, and together we can get this done.”

Former vice president Joe Biden’s climate plan calls for the complete elimination of carbon pollution by 2035. Angerer / Getty Images

In his plan, Biden calls for the complete elimination of carbon pollution by 2035. He also promises to rejoin the international Paris climate accord, which Trump withdrew the United States from in 2017. While Trump continues to dismiss the science behind climate change, Biden’s plan uses climate science and the projections of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change as a foundation. Biden’s plan will focus on investing in renewable energy development and creating incentives for industry to invest in energy-efficient cars, homes and commercial buildings. Biden has pledged to end new oil, gas, and coal leases on public land and has said he will emphasize more solar and wind energy projects on BLM land.

Despite their initial reservations, many environmental organizations and climate activists have been won over by Biden’s new approach. In August, the Sierra Club officially endorsed him. The Sunrise Movement, which agonized publicly over the choice, said that though it would not formally endorse Biden — the group has an endorsement process with specific benchmarks, including requiring candidates to sign a “no fossil fuel money pledge,” in which lawmakers promise not to accept money from PACs or from donors in the extractive energy sector — it would campaign for him. “What I’ve seen in the last six to eight weeks is a pretty big transition in upping his ambition and centering environmental justice,” Varshini Prakash, co-founder and executive director of the group, told the Washington Post.

“What I’ve seen in the last six to eight weeks is a pretty big transition in upping his ambition and centering environmental justice.”

In August, Biden named Kamala Harris as his running mate — a signal to his constituency that she would bring accountability to the promises he has made regarding climate action. Harris, who has a strong record of environmental action, made it a centerpiece of her own failed run for the presidency. She and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the progressive congressperson from New York, introduced the Climate Equity Act, which would establish an executive team and an Office of Climate and Environmental Justice Accountability to police the impacts of environmental legislation on low-income and communities of color. Harris has also said that she wants to eliminate the filibuster — which is a tool most often used for hyper-partisan gridlock — in order to clear the way for the passage of the Green New Deal, a progressive package that aims to mitigate the worse impacts of climate change while transforming the U.S. economy toward equity, employment, and justice in the country’s workforce.

If Biden is elected, his nomination to lead the Interior Department and the Bureau of Land Management will have great significance for his climate agenda. Potential nominees include Representative Raúl Grijalva, a Democrat from Arizona and the chair of the House Natural Resources Committee; Ken Salazar, Obama’s Interior secretary; and John Podesta, a lifelong Democratic operator and former chief of staff under Obama, who is credited with envisioning that era’s most memorable conservation and environmental achievements, such as the Climate Action Plan and an economic recovery bill that invested $90 billion in renewable energy and energy efficiency.

Biden has signaled that he’d name a preservation-minded Interior secretary. When Trump withdrew William Perry Pendley’s nomination, Biden responded on Twitter. “William Perry Pendley has no business working at BLM and I’m happy to see his nomination to lead it withdrawn,” Biden wrote. “In a Biden administration, folks who spend their careers selling off public lands won’t get anywhere near being tapped to protect them.”

Folded neatly on the countertop that divides Tye Hess’s kitchen from his living room was a large navy flag decorated with stars and a bright red stripe and the declaration: TRUMP 2020, NO MORE BULLSHIT. It was a sunny afternoon in July in Redlands, a suburb of Grand Junction. The streets and culs-de-sac in Hess’ neighborhood are named after the local wine scene; Hess lives on Bordeaux Court.

“How many flags have you sold this week?” I asked. He exhaled loudly. “Quite a few, probably like 20,” he said.

Hess has short brown hair, bright blue eyes, and a small gap between his teeth. He was wearing a Pink Floyd T-shirt and casually sipped a ruby grapefruit White Claw as we spoke.

“On Friday, I’m getting much more in, and I’m just going to start handing them out to people saying that if they want to donate to buy more, they can,” he told me. “I feel guilty, ya know?” He laughed. “It’s just something I believe in, so I don’t feel like charging for them. I’ve made plenty of money off these, and I can afford to give some away. But if somebody wants to donate money to buy another one, I’ll do that. Just keep it going.”

Hess typically sells the flags for $25. When I met him, he had already sold more than 200, hand-delivering each one, and setting up the deals through social media. Previously, he worked for a coal mine, overseeing methane flaring outside of Paonia, Colorado, and then working as an independent contractor, installing granite countertops, carpet, and tile. He supplements his income by running his own e-commerce store. He views his flags project as a personal campaign trail. “We have to do everything we can to get him reelected,” he said. Hess, who is 42, only registered to vote a few months before we met, and this election will be his first.

We were waiting for a customer named Eric Farr, who was picking up today’s flag. Hess threw away the White Claw, opened his refrigerator, and grabbed a Coors Light. The doorbell rang.

Farr seemed surprised to see me, even though Hess had told him a reporter would be at the handoff. “You’re not some super liberal lady who is going to spin everything I say, are you?” he asked. I promised him that I wouldn’t. “OK,” he said.

“I just want to keep the public lands open, like the BLM area. It’s just free and open space. I just want to keep a lot of it open for the motorcycles and side-by-sides.”

Farr was born in the mid-1980s at St. Mary’s Medical Center, in Grand Junction. He grew up riding a Yamaha YZ125 motorbike, honing a talent and a love for motocross on the dips and yaws of the town’s bluffs, managed for motorized use by the BLM. He had traveled widely, competing professionally on his Yamaha and sponsored by Jägermeister. “I have been all over the world, but never wanted to live anywhere else,” he told me. “I just want to keep the public lands open, like the BLM area. It’s just free and open space. I just want to keep a lot of it open for the motorcycles and side-by-sides.”

As we talked about the land, I asked Farr what he thought of Trump’s refusal to fill the position of director at the BLM. “With everything going on, I haven’t seen anything about (Trump’s) approach to public lands,” Farr replied, referring to the pandemic and the ongoing demonstrations for Black lives. “It seems like Trump is about letting the states do what they feel is best with their public lands. So I think he’s got enough on his plate that he doesn’t really have time. As important as public lands are, there are a million other things that are just as important that he’s focused on.”

I asked whether Farr was worried about future generations being able to mountain bike, e-bike, and dirt-bike the rocky plateaus and canyons, the same lands that have been such a large part of his own life.

“I get real upset when people dump their trash out there, because that’s going to get them shut down quicker than anything probably,” he said. He thought Trump was the country’s best hope for a return to aspects of his childhood he values: “constitutional values,” he said, “what the founding fathers tried to instill into our country.” He told me that he wants his children — he has two children under 7 and a baby on the way — to experience the same freedom that he feels he grew up with. “I’m not a Democrat, I’m not a Republican,” Farr told me. “I’m a patriot. Trump is like our savior basically. He’s our only hope.”

BMX bikers compete at a race in Grand Junction, Colorado, a hotspot for the sport. Carlos Herrera / Icon Sportswire via Getty Images

“Yep, I just barely registered [to vote] because of Trump and seeing these idiots,” Hess said, referring to the social justice activists protesting in Grand Junction following the killing of George Floyd by police in Minneapolis. “I’ve had plenty of disagreements, and I never seen such rude comments [on social media]. Then you fight back and they play the victim.”

Hess took another Coors out of the refrigerator and handed it to Farr. “It’s just ignorance and — like you said — victim mentality,” Farr said to Hess, taking the beer.

I tried to steer the conversation back to the Interior Department, but they wanted to focus on what they called the gall of the “radical socialist left.” Though both Hess and Farr’s lives have been intimately connected to the public lands in the Grand Junction area, the fate of those landscapes has not factored into their calculus for November’s election.

About a week later, a lightning bolt 18 miles north of Grand Junction ignited the Pine Gulch Fire, a blaze that became the largest wildfire in Colorado’s history. By early September, it had burned around 140,000 acres, mostly on BLM land. It pushed northwest, forcing evacuations for residents who live next to abandoned wells in the town of De Beque, down the road from Rifle, the home of Shooters Grill.

For weeks, Grand Junction was shrouded in wildfire smoke. Since we first talked, Hess and his fiancée had moved to the rural edges of the county. From Hess’ home, he could barely make out the rows of peach trees just beyond his property line under the dense sepia-toned sky. In a photo he sent me, the sun burned an electric scarlet; he told me he was worried for the wildlife.

I imagined what someone standing in the new headquarters of the BLM might be able to see. When I visited the office in July, the sky was bright blue and clear, with mere scraps of clouds offering a respite from the heat. From its north-facing windows, you could see the Grand Valley Off-Highway Vehicle Area, where Farr loves to ride. To the southeast was Lunch Loops, the mountain biking area that Shrader can pedal to in just minutes from her front door, and the entrance to Colorado National Monument.

Due to the pandemic, most employees were telecommuting, and very few people were there, save for a few construction workers fixing electrical issues on the third floor. They were from Shaw Construction, one of the BLM’s neighbors in the building. The BLM also shares the building with Chevron, the Colorado Oil and Gas Association, Laramie Energy, and ProStar Geocorp, a mapping company. In the middle of a move, the BLM headquarters was a scene in flux, a place still trying to realize itself.

Along the halls of the BLM’s office, large murals of iconic scenery — Colorado National Monument, Black Canyon of the Gunnison — leaned against bare walls, waiting to be hung. I remembered talking to Hess about his city as a new nexus for public lands management, and asking him what he thought about moving the BLM headquarters from Washington, D.C., to Grand Junction. Hess just laughed: “The BLM headquarters is here?”