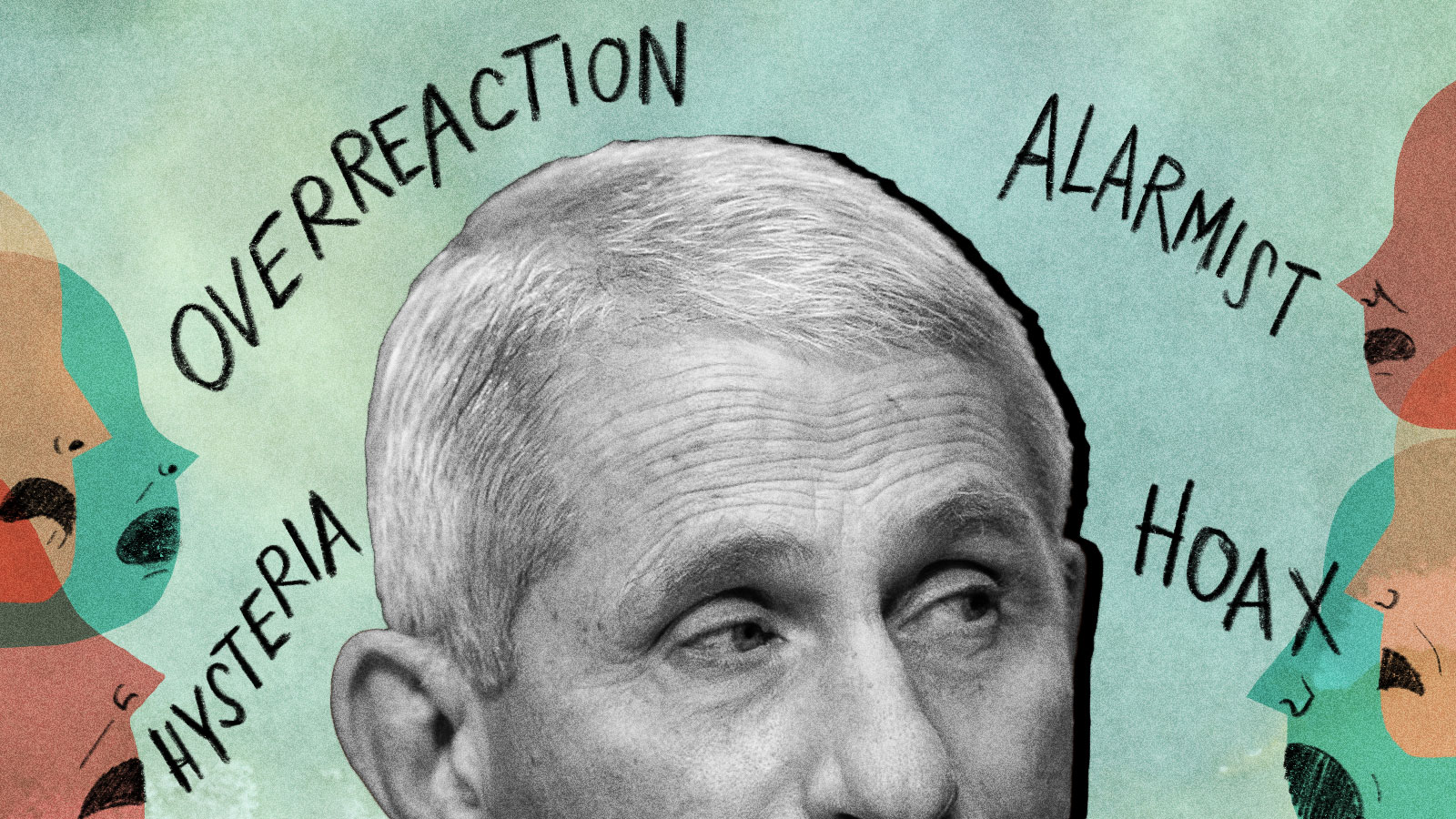

In an interview with Fox News in June of 2020, then President Donald Trump called Anthony Fauci, the country’s top infectious disease expert, an “alarmist,” using a pejorative straight from the playbook of those who deny the science behind climate change. Fauci rejected the characterization, describing himself as a “realist.”

For anyone paying attention to arguments about climate change over recent decades, Trump’s comment sounded awfully familiar: Scientists are alarmists, everything’s a hoax, and hysteria abounds. Michael Mann, a climatologist at Penn State University, wrote an op-ed for Newsweek this week drawing parallels between his experience and Fauci’s during COVID-19. Science deniers have lobbied attacks on the two public figures, he explained, sending death threats, calling them names, and questioning their expertise.

So what do terms like alarmist and hysteria really mean, where did they come from, and how can people respond to such accusations?

The strategies used to dismiss the threats of climate change and coronavirus follow a similar pattern, and they’re employed by many of the same people. It starts with denying the problem exists, as Naomi Oreskes, a professor of history at Harvard who studies disinformation, has explained. Then, people trying to obstruct action deny the severity of the predicament, say it’s too hard or too expensive to fix, and complain that their freedom is under threat. Denying the science requires dismissing what scientists are saying, and the easiest way to do that is by questioning their motives, impartiality, and rationality.

“If we don’t trust scientists or medical experts because we see them as alarmist or hysterical or as contributing overreaction, then we don’t trust the info they’re giving us,” said Emma Frances Bloomfield, an assistant professor of communication at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

Back in the day, alarmism was seen as a virtue. The term traces back to the 1790s, around the time that Edmund Burke, the famous philosopher, sounded the alarm against the French Revolution. “We must continue to be vigorous alarmists,” he wrote.

That “sounding the alarm” connotation faded long ago. Now it suggests a person who exaggerates and sensationalizes potential dangers, sowing needless panic. It’s a pejorative that doesn’t fit most scientists. Research has shown that they’re fairly conservative when it comes to the climate crisis. A 2012 study found that their projections have actually underestimated the effects of our overheating planet, like the potential disintegration of the West Antarctic ice sheet. The authors of that study, including Oreskes, wrote that “scientists are biased not toward alarmism but rather the reverse: toward cautious estimates.” They called this tendency “erring on the side of least drama,” and suggested that the tendency to downplay future changes comes from a pressure to appear objective.

The commonly held notion of what a scientist should be was articulated by Robert K. Merton, an American sociologist who outlined the “ideal” expectations for scientists in the 1940s. Merton called for scientists to be unbiased, rational, and to stay clear of conflicts of interest.

Words like overreacting emphasize emotion, detracting from scientific credibility. “Being emotional is something that we try to keep away from science,” Bloomfield said. “When you think about scientists really caring about something, it violates those expectations we have that scientists are balanced and they only look at facts.”

Take hysteria, which comes from the Greek word for uterus. (Plato and Hippocrates thought the womb lurched up and down in the body, causing erratic behavior, emotional outbursts, and insanity among womankind.) The term has a dark and complicated history, but suffice it to say that it made an appearance in 17th-century witch trials, and much later on, during some pretty frustrating visits to the doctor.

“It’s feminizing science as a way to discredit it,” Bloomfield said. Another word to keep an eye out for is shrill, an adjective describing a high-pitched, piercing voice that became a way to stigmatize women (think Hillary Clinton) and sometimes scientists, too.

To counter these attacks, Bloomfield said that one effective strategy is to follow Fauci’s example: Reject the characterization and substitute your own word, like realist instead of alarmist.

Another strategy is to ask questions that challenge assumptions. Bloomfield suggests asking something like, “How many people would have to die for you to be alarmed?” With 164,000 deaths and climbing, more Americans have died from COVID-19 than were killed in World War I. The question forces people to think for themselves and draw their own conclusions.