The Center for American Progress has released a new survey of public opinion on energy issues, conducted by Hart Research. For a basic rundown of the results, see Emily Atkin, whose headline captures them well: “Voters Want Pretty Much the Opposite of What Congress Is Doing.”

Meanwhile, there’s a new Washington Post/ABC News poll that contains interesting results on Keystone XL, ably summarized by Aaron Blake on Wonkblog.

Let’s start with the latter and make our way back to the former.

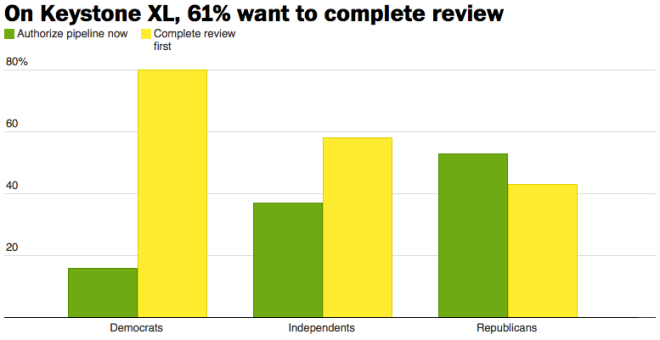

It turns out that while majorities of the public favor the Keystone pipeline, equally large majorities favor completing the government’s review before deciding whether to build it:

Blake posits three possible explanations for why voters say they favor cautious patience on Keystone. It’s his third that seems closest to the mark to me:

3) Support for the pipeline is wide but shallow. We doubt that too many people have thought long and hard about this issue, including both the economic and environmental impacts. Thus they are less insistent that it be built immediately.

I would put it a bit differently. Though it may be impolitic to say so, the basic presumption behind almost all issue-specific opinion research or media coverage should be deep public ignorance. Most Americans don’t know much about any of the stuff that obsesses politicos, even down to which party controls Congress or what the three branches of the U.S. government are. How many Americans know what kind of oil the Keystone pipeline will carry, who will build it or profit from it, where it will carry the oil, what the economic or environmental effects will be? I’d wager on the order of 2 percent, optimistically. Never mind long and hard — I doubt most Americans have thought about Keystone at all.

Here’s a telling contrast. Most polls show that a roughly 60 percent majority of Americans favor building Keystone. But in the Hart poll, they asked an open-ended question: “What would you most like the president and Congress to do related to this issue?” When “this issue” was energy, just 7 percent offered up Keystone voluntarily. It is engaged partisans, and engaged partisans only, for whom this is a salient issue.

Then again, Americans don’t seem to have strong, spontaneous feelings on much of anything energy-related:

This lack of strong opinion is consistent with ignorance, which is to say, most people don’t have considered thoughts on energy or environmental policy.

(Obligatory caveat: to say the public is ignorant on policy issues is not an insult. It’s not to say people are dumb; it’s just that people are busy. They have lives and limited free time.)

So how should we interpret these poll results? I’d say a good rule of thumb is that, depending on the issue, around 20 to 30 percent of public opinion is represented by strong partisans on either side, who are the most likely to be familiar with the issues. The rest, that vast swathe of people who have busy lives and no time or particular incentive to study up on matters of policy, will generally gravitate to things that sound good.

This crude sounds-good/polls-good heuristic will get you about 90 percent of the way to understanding most poll results on “issues,” including energy and environment. Accessing more oil sounds good. A judicious review also sounds good. More domestic oil production sounds good, but exporting American oil to other countries sounds bad. Advanced, cleaner energy sounds good, as does cleaner air. “Balance” sounds good (better than “all of the above”), and so does “independence,” but doing the bidding of Big Oil sounds bad.

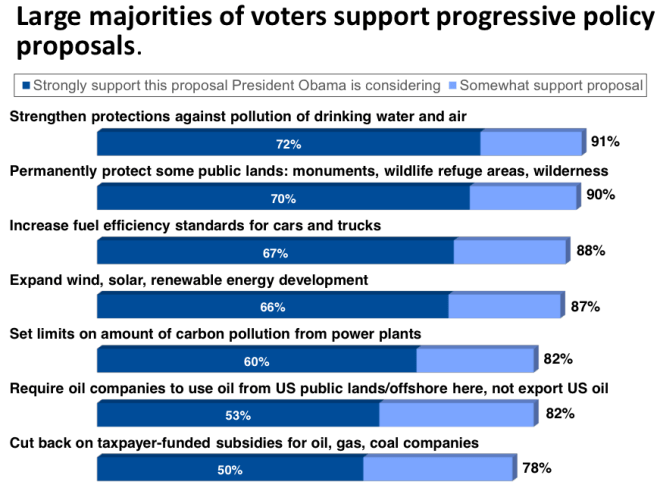

The advantage of the progressive energy agenda is that most of it sounds good:

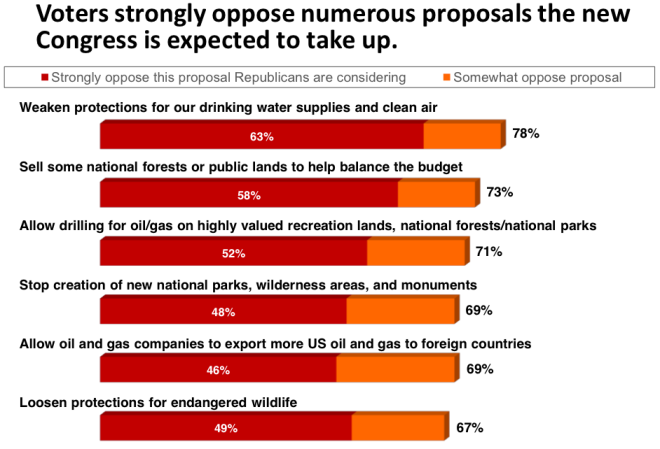

Meanwhile, most of what the Republican Congress wants to do on energy policy sounds bad:

None of this is a big surprise. Stuff that sounds good, like clean energy and clean air, has always polled well.

But! That’s not the end of the story. It is well-known that the American public is symbolically conservative but operationally liberal, which is to say, they prefer conservative self-identification and abstract conservative principles like “small government” and “low taxes,” but when it comes to specific policies, specific government programs and initiatives, they overwhelmingly side with liberals.

Precisely because of this paradox, however, it is dangerous to use these polls as evidence that progressives are more likely to win on energy/environment issues. “Strengthen vs. weaken pollution protections” is the battle progressives want to fight. But conservatives want to fight a different battle: “grow vs. shrink government,” or “pass vs. block job-killing regulations.”

Partisans on either side will adopt their side’s frame. Partisan conservatives know that “pollution protections” is just commie talk for “job-killing regulations.” Partisan liberals know the inverse. (Just FYI, partisan conservatives outnumber partisan liberals.) What the mushy, disengaged public thinks about a specific political dispute will hinge in large part on which side’s frame it hears most loudly or most often, or finds more amenable in a particular instance. That’s what it means for public opinion to be “shallow” — it sloshes back and forth depending on circumstances, emphasis, and rhetoric.

What lessons should political leaders learn from all this? To me it seems simple: on the issues, it is futile to try to chase what polls well. Shallow public opinion is not a stable foundation for political success. Instead, do what’s right on the substance, strive to tell your own story about it, and don’t worry about sloshing opinion. Because most of the public doesn’t have particularly strong opinions on “issues,” it’s unlikely that any policy issue will have a substantial effect on election results. What decides elections are the fundamentals, not policy disputes, much less cable-news fodder like gaffes and pseudo-scandals.

So do what’s right and trust the politics to sort itself out. The conservative movement understands that — they’ve long been willing to defy public opinion on specific policies, knowing they still dominate the battle of abstract frames and tribal identifiers.

It would be nice if the progressive movement fought harder and smarter on the battlefield of big-picture framing. But in the meantime, compromising on specific issues is the worst of both worlds. It capitulates where progressives are strongest, on the issues, and gains nothing in the larger framing battle.

If Obama blocked Keystone tomorrow, there would be a hubbub that lasted for a few weeks, then the issue would recede to the partisan press, where only partisans would care about it. It won’t dent any election outcome. The same goes for EPA regulations and the other executive actions Obama is contemplating.

To his credit, at least since the midterms, Obama seems to get it. He’s acting boldly on climate, immigration, and family leave through executive action and refusing to worry about the clucking it engenders among the chattering class. And it is redounding to his favor. Results are what matter.

So just make good policy and polls be damned.