This story was originally published by The Guardian and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Environmentalists have been heartened by Joe Biden’s victory as, if the United States rejoins the Paris Agreement as expected, it will give the world a much better chance of averting climate catastrophe. However, there are still hurdles to overcome to rein in emissions and keep warming to within 1.5 degrees C (2.7 degrees F) above preindustrial levels.

Dirty financing by China, Japan, and South Korea

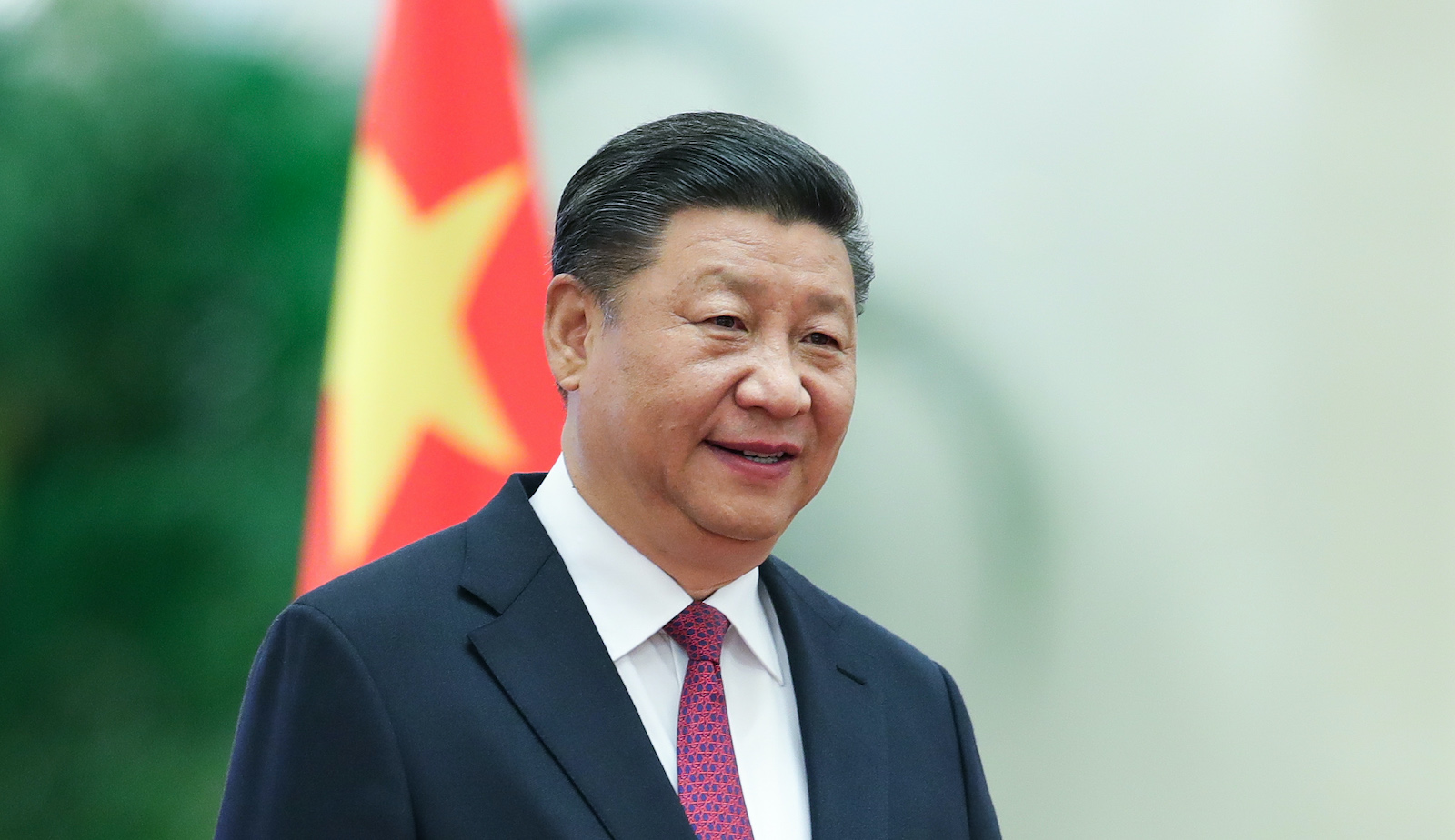

Xi Jinping’s promise to make China carbon-neutral by 2060 generated optimism, but state and provincial institutions do not seem to have received the memo. Lintao Zhang / Getty Images

“Drinking poison to quench thirst” is how energy analysts describe China’s efforts to boost economic recovery by pumping money into dirty industries such as coal. No nation is as important to the global climate as China, the world’s biggest emitter, which is why President Xi Jinping’s promise to make his country carbon-neutral by 2060 generated optimism around the world.

But state and provincial financing institutions do not seem to have received the memo. A Guardian-commissioned ranking of national green recovery plans put China last among major economies, with only 0.3 percent of its stimulus package set aside for renewables and other sustainable projects. Instead, there has been a glut of new domestic coal financing.

Similarly, dirty power projects dominate energy spending overseas on the Belt and Road Initiative, China’s global infrastructure development strategy introduced in 2013 to invest in nearly 70 countries and international organizations. Analysts say this needs to change if the world is to have any chance of keeping temperature rises to the Paris Agreement goal of between 1.5 degrees C (2.7 degrees F) and 2 degrees C (3.6 degrees F).

Much will depend on China’s next five-year plan, being drawn up by the central committee. Although these deliberations have received scant media attention compared with the U.S. election, they are more important in climate terms. Energy experts say an ambitious Chinese strategy would reduce coal use to less than 50 percent of the energy mix and increase renewables to around 25 percent by 2025. If the government also put in place an emissions cap, it would mark a positive step forward.

More important still would be a commitment to shift the focus of Belt and Road investment to renewables, which could see China leading the global transition away from fossil fuels. “The most critical recovery is China,” says Bob Ward of the Grantham Institute at LSE. “It holds a lot of debt in other countries and funds dirty industries overseas. If it continues, then it will undermine global efforts to cut emissions.”

The world’s other two main coal financiers, Japan and South Korea, also have a role to play. Both recently set 2050 zero-carbon goals, which is encouraging in the long term, but if their governments are serious about climate action, they need to overcome resistance from old-fashioned industries — notably Toyota and Hitachi in Japan and Doosan in South Korea — and send a clear message that all future investment must be fossil-fuel free.

U.S. political division

Joe Biden is expected to rejoin the Paris Agreement in January. Joe Raedle / Getty Images

Donald Trump has been the face of climate denial for the last four years, but his defeat will not be enough to transform the United States into an engine for global green recovery unless the Democrats can regain control of the Senate.

Joe Biden, the science-friendly president-elect, is already assembling a team of climate experts. On taking office in January, he will almost immediately rejoin the Paris Agreement. Whether this will be anything more than a symbolic victory will depend on the division of power in Congress.

If the Democrats can win the Senate runoff in Georgia and tie the number of seats in the upper chamber, then the vice president-elect, Kamala Harris, should have the deciding vote on climate legislation and budgets, such as the $2 trillion green new deal promised in the campaign. If, on the other hand, the Republican party maintains control of the Senate, it is likely to continue to block ambitious action and international cooperation, as it did during the Clinton and Obama presidencies. Powerful lobbyists, well-funded by the likes of Exxon, Chevron, and Koch Industries, will also continue to deny, delay and disrupt. Legal challenges will go to the most conservative Supreme Court in recent memory.

Rob Jackson, chair of the Global Carbon project, fears division will once again stymie action at the national level. “I don’t see a path to the Green New Deal in the current political climate here,” he says. “A divided Congress would almost certainly mean that a big-picture climate bill wouldn’t happen over the next two years, and president Biden will be unlikely to get anything big through Congress.”

All is not lost. Jackson notes state-level actions have been leading the climate agenda in the United States regardless of who is in the White House. Another big question is whether Wall Street will call time on fossil fuels, which would change everything. Unlikely as it seems, if the United States could unite around a massive green stimulus program, this would ripple positively across the world.

European industry lobbying

Industry organizations including Airlines for Europe and Airlines for America have influenced Brussels to relax or drop emissions trading requirements. Santiago Urquijo / Getty Images

Europe is setting the green recovery pace, but it would be progressing at a substantially faster clip were it not for lobbying by powerful, carbon-intensive industries such as farming in France, coal in Germany and Poland, or oil in the U.K. and the Netherlands.

This is also true for the aviation sector, which has evaded responsibility for cutting CO2 in national climate plans. Airbus, Lufthansa, KLM, and other carriers have long campaigned against higher airline taxes, binding targets for green fuel, and low-carbon aircraft. Industry organizations including Airlines for Europe and Airlines for America have influenced Brussels to relax or drop emissions trading requirements.

Industry watchers say this resistance may be softening because of COVID, with airlines and plane-makers desperate for bailouts. This gives governments the leverage to insist on something in return. In Germany, Lufthansa has been told its public advocacy must align with Europe’s climate objectives, which should halt lobbying against ambitious green standards and stronger obligations under the emissions trading scheme. In France, the head of Airbus, Guillaume Faury, is starting to talk of “carbon-based decision making.” He wants to take advantage of a scrappage scheme to replace older polluting aircraft with cleaner new models and to win funding for research into hydrogen or electric aircraft. Spain, now the fastest mover in Europe, is mandating greater use of clean fuels.

Not all the changes are as progressive as they seem. In the Netherlands, KLM has become an enthusiastic supporter of higher standards for inter-European flights, though that is less impressive when you realize this accounts for only 20 percent of its business.

Andrew Murphy, aviation director at the NGO Transport & Environment says he is cautiously optimistic. “Things are changing in the way industry is behaving. Because they need government support, they are not openly opposing action as they used to do,” he says.

The crucial test will be a debate about the E.U.’s revised emissions reductions targets. “That will be a big decision,” says Murphy. “The E.U. should be explicit that aviation is included in emissions targets.” Just as important, he says, will be Europe’s willingness to move ahead without waiting for the rest of the world and the laggard U.N. aviation agency, Icao, which has been susceptible to industry pressure, particularly from the United States.

U.K. failing to set example as COP26 host

COP26 is likely to be the most important international event of Boris Johnson’s tenure. Leon Neal / Getty Images

“Mind the Gap” should be stamped across the top of every climate briefing document handed to Boris Johnson over the next year, or the U.K.’s hopes of hosting a successful U.N. climate conference will founder in accusations of hypocrisy.

COP26 is likely to be the most important international event of the prime minister’s tenure. The gathering, in November 2021, aims to go a step further than the Paris Agreement, prompt governments to set more ambitious targets, and put the world back on track to keep global heating to between 1.5 degrees C (2.7 degrees F) and 2 degrees C (3.6 degrees F) above preindustrial levels. It is also the most likely way for “Britain’s Trump” to reach out to Biden, with whom he shares little common ground.

In public, Johnson is increasingly positive about climate action, but he has a long way to go before he can convince anyone he is genuinely enthusiastic. As a newspaper columnist, his position on cutting emissions was lukewarm; as an MP, his climate voting record was even cooler.

The U.K. also has a gap to make up. Successive governments have presented themselves as global climate leaders. This administration boasts of being a frontrunner in setting a 2050 goal for carbon neutrality. But climate campaigners say long-term targets are irresponsible unless matched by action in the near term. The U.K. is still off course, even for the goals it set five years ago.

Long-term observers say the moment ought to be ripe to make a big change after COVID. Until now, however, “green recovery” plans announced by the government have failed to impress.

“My feeling is this government would be in a better place to do a proper green new deal than any previous because of it clearly being an interest of Johnson’s, and because the fiscal constraints are suddenly off,” says Douglas Parr, chief scientist and policy director at Greenpeace U.K. But he fears this is not yet a sufficiently urgent political priority, the public is wedded to cars, and U.K. institutions such as Ofgem, the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS), and local authorities are not designed or funded enough to act at the speed and scale of change required.

Others fear Johnson’s inner circle contains too many skeptics, including those who previously worked for right-wing think tanks such as the Institute of Economic Affairs and TaxPayers’ Alliance, both of which opposed proposals for a green new deal after the 2008-9 financial crisis.

Many senior conservative politicians, despite talking up a green recovery from the pandemic, remain wedded to old industries. New data from the investigative journalist group DeSmog U.K. found BEIS ministers met BP, Shell and other fossil fuel producers almost 150 times in the early months of the lockdown, and renewable energy producers only 17 times.

“The government doesn’t reveal what is said in those meetings. But the level of access the industry gets implies that, at best, ministers are mainly listening to big polluters when planning a green recovery, or at worst are disregarding it in order to prop up the fossil fuel industry,” says Mat Hope, the editor of DeSmog U.K.

Whichever is true, there is a credibility gap to close if the next COP host wants to lead by example.

Global disinformers, delayers, and deniers

Jair Bolsonaro says environmental NGOs trying to protect the Amazon are part of a foreign conspiracy to stifle economic development. Andressa Anholete / Getty Images

From Rupert Murdoch’s media empire to populists such as the Brazilian president, Jair Bolsonaro, right-wing resistance to pro-climate government intervention takes many forms. But a starting point is disinformation: undermining climate science in the opinion pages of the Wall Street Journal or the Australian, downplaying the link between human emissions and extreme weather events such as fires, floods, and droughts in news reports, or distracting attention with false equivalences such as the recent call on world leaders to “fight the virus not carbon” by the Climate Intelligence foundation (Clintel), a European group opposing climate action with links to British Conservatives and similar parties in the European parliament.

Opponents of green new deals say they are poor value for money and climate risks are exaggerated. In the U.K., the Global Warming Policy Foundation, co-founded by the former U.K. chancellor Lord Lawson, recently put out a paper warning against a post-COVID green recovery package on the grounds that more wind and solar would make energy more expensive. Similar arguments are put forward in two recently published books by Bjorn Lomborg and by Michael Shellenberger.

Critics say such claims are refuted by the sharply falling costs of renewables, which are often now cheaper than coal and oil, and the cost of inaction: worsening forest fires, droughts, hurricanes, and floods.

The increasingly evident global toll of the climate crisis makes out-and-out denial all but impossible. Instead, the extreme right shift their doubt-mongering toward ideology. Brazil’s foreign minister, Eduardo Araújo, suggests climate campaigns are part of a global Marxist plot. His boss, Bolsonaro, says environmental NGOs trying to protect the Amazon are part of a foreign conspiracy to stifle economic development. Neither has provided a shred of evidence to back up their accusations.

Brazil, meanwhile, is heading in the opposite direction of a green new deal. The state-led oil company Petrobras recently sold off its shares in renewable energy. The government is basing its hopes for economic recovery on opening up the Amazon to more mining, farming, and logging. Once Trump leaves office, Bolsonaro will replace him as the global face of climate disruption.