When I first saw Mary Iverson’s paintings on Instagram, they didn’t scream “THIS IS ART WITH AN ENVIRONMENTAL MESSAGE!” They are commentary on climate change, sure, but said commentary is delivered through more of a soft murmur than a belligerent yell. Iverson, a Seattle-based painter and public artist, started addressing environmental issues and climate change in her work in 2009, and has since created many pieces that are compelling without going over the top. I got to chat with her about her about her process, why we need more women in art, and what’s really so appealing about shipping containers.

The conversation below has been edited and condensed.

Q. How did your series of paintings on climate change get started?

A. I’ve been following the shipping industry for several years and doing paintings of the growth of that industry. While I was painting the beauty of those shapes and colors of containers and cranes and ships, I’ve been researching the impact of the industry on the natural world, and also of course paying attention to climate change, climate science.

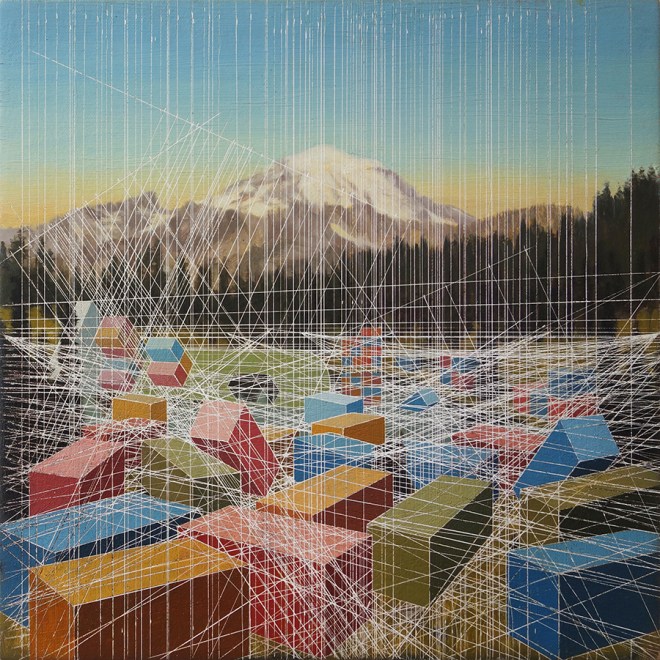

In the current series [which I started in 2013], I’m just exploring what rising sea levels would look like in some of our major cities — just sort of imagining the big flood in those cities, and all the buildings and putting my shipping containers and cargo ships in the water, surrounding them, kind of like a post-apocalyptic vision.

Q. What first pushed you to start addressing climate change in your art?

Mary Iverson.

A. I was noticing the discrepancy between my interest in environmental activism, and then my paintings, which were of container ships and containers and are a reflection of the growth of our economies and the growth of populations, so I had trouble reconciling my heart with my imagery in my work. In about 2009, I started developing work that addressed the impact of the shipping industry and population growth on our national parks and environment and world in general. That started when I started combining my container ship imagery with my landscape imagery.

Q. And how did you first get started painting shipping containers?

A. I was a landscape painter, really dedicated, for about three years, and I would take my easel out every day and find good spots [to paint.] I started getting interested in the warehouses and Harbor Island and some of the industrial areas in Seattle, just because they were really quiet. And then I started narrowing in on the port and the cranes, and did a series of paintings on the orange container crates. And then it got the attention of someone at Stevedoring Services of America, and they said: “Hey, would you like to do a project for us? I’ll give you a pass to get on the terminal so you can go paint right at the source.” So every day I was out under the cranes and with the ships, and just making paintings from right there. [I was also] meeting electricians and stevedores and longshoremen, and really getting a flavor of the whole system of the port.

Q. When I first moving to Seattle I was looking at an apartment with some people in the Industrial District, by the port. This girl who had lived there for a while told me, “I think that this is one of the most peaceful parts of the city, I feel like I’m on a prairie when I’m walking around here at night.” Because it’s so eerie and deserted that it kind of reminded her of the countryside where she grew up.

A. Wow, that’s a really cool perspective! It’s very quiet, yeah. A mystery land!

Q. Yeah, it really is. So when you mentioned that you started to feel kind of conflicted about focusing on this industry, how did that conflict manifest itself?

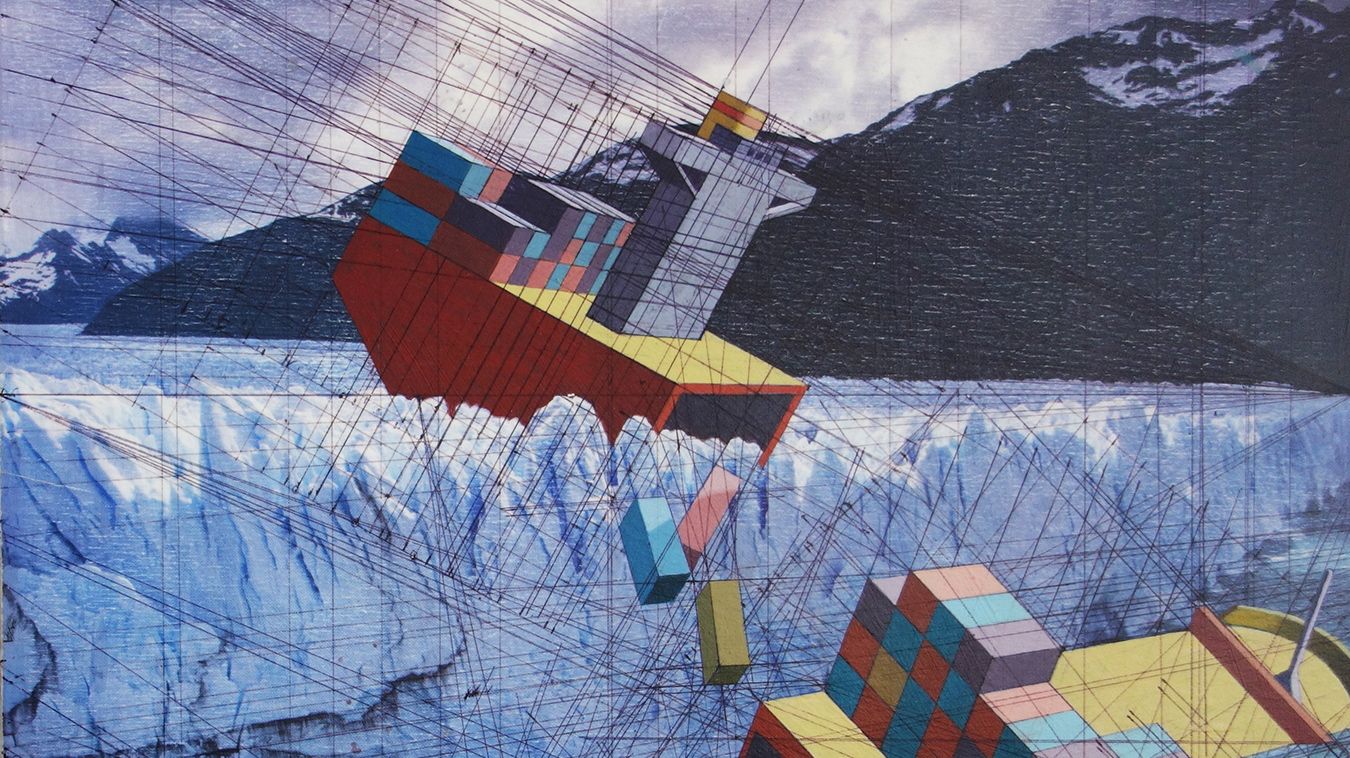

A. Well, I realized it wasn’t totally authentic for me to just be painting the containers without also communicating what I was learning about the industry and the growth of ports and ships and stuff. And so I started flipping through magazines, like National Park Magazine, and Sierra Magazine, and Smithsonian and Audubon, and I’d find these pristine images of these protected places, and then just throw my containers into them! So that it showed this beauty of the sharp-edged and the organic together, but then when you started thinking about it, it’s like — oh my god, this isn’t beautiful, this is a disaster.

Then I started working it through with larger paintings, and visiting sites that I wanted to do paintings of. I went to Yosemite National Park, Olympic National Park, Rainier National Park, and got imagery for the natural settings, these pristine settings that we protect, and then I drew my shipping industry imagery into that setting.

Q. And when you say that you were learning things about the shipping industry — what were they, exactly?

A. Well, the most striking thing is the growth of the industry, and it’s a really silent thing — like most people aren’t even aware that the goods we purchase are shipped over on these container ships, you know? Especially if you don’t live in a port city, you’re just not aware of the enormity of the commerce. And so I started researching volumes, like how many a day come into each port. As population grows, the market grows, and the ships grow, and the demand for goods grows. Because of our consumerism and the growth of the population, everything’s had to grow and grow and grow, so you get a big impact.

Q. Did you feel like this kind of juxtaposition of industry growth and beautiful, pristine natural spaces is particularly applicable to Seattle?

A. As a city, our identity is kind of split in the same way. I found myself split, because [a major] economic engine of our city, it could be argued, is the port. The jobs created, and the vitality of our city has a lot to do with having a port. We’re embracing that and then at the same time, we’re a town full of liberals and greenies — like the kayaktivists — and there’s this deep-seated respect and love of nature and our national parks. The identity of Seattle lies in being this rainy place with nature right next door. So it was kind of this split personality, locally — and so in my work, I’m trying to reconcile that, in a way.

Q. These are not your typical overwrought, super-earnest environmental pieces, either. What do you think are the main pitfalls of art with an environmental message?

A. I think that the pitfalls [occur] when the message is ultra-specific, and what I think is strong about the message in my work is it just proposes a thought. The paintings don’t hit you over the head with it — it leaves a lot for the viewer to supply, you know? Of course, there’s some amazing work that’s very direct and specific, but I just like to present what’s going on more dispassionately. I’m not a neutral observer, but I am an observer before I’m an activist, in a way. I’m observing that these things are in discord, and then I’m presenting that, and then just leaving it to the viewer to figure out what’s going on.

Q. Who or what would you say are some of your main artistic influences?

A. Albert Bierstadt and Frank Stella. I’m sad there’s not a woman in there — I cast about for that, but the reality is that those are my two biggest influences.

Q. That is something that’s always pissed me off, that women have to have guilt about not picking women as their main influences.

A. I know! I think that the next generation of women artists and writers will be able to absolutely say, oh this woman is my main influence. We’re getting there, I think, but history is just too laden with men. It’s not our fault, right?