Hello everyone, and welcome to another week of Parched. I’m Zoya Teirstein, and today we’re going to talk about the flash drought in the Northeast.

This year marks the 22nd year of drought in the Western United States, something meteorologists anticipated based on recent precipitation data and climate change trends. They were less prepared, however, for the drought data that trickled in this summer from parts of the Northeast.

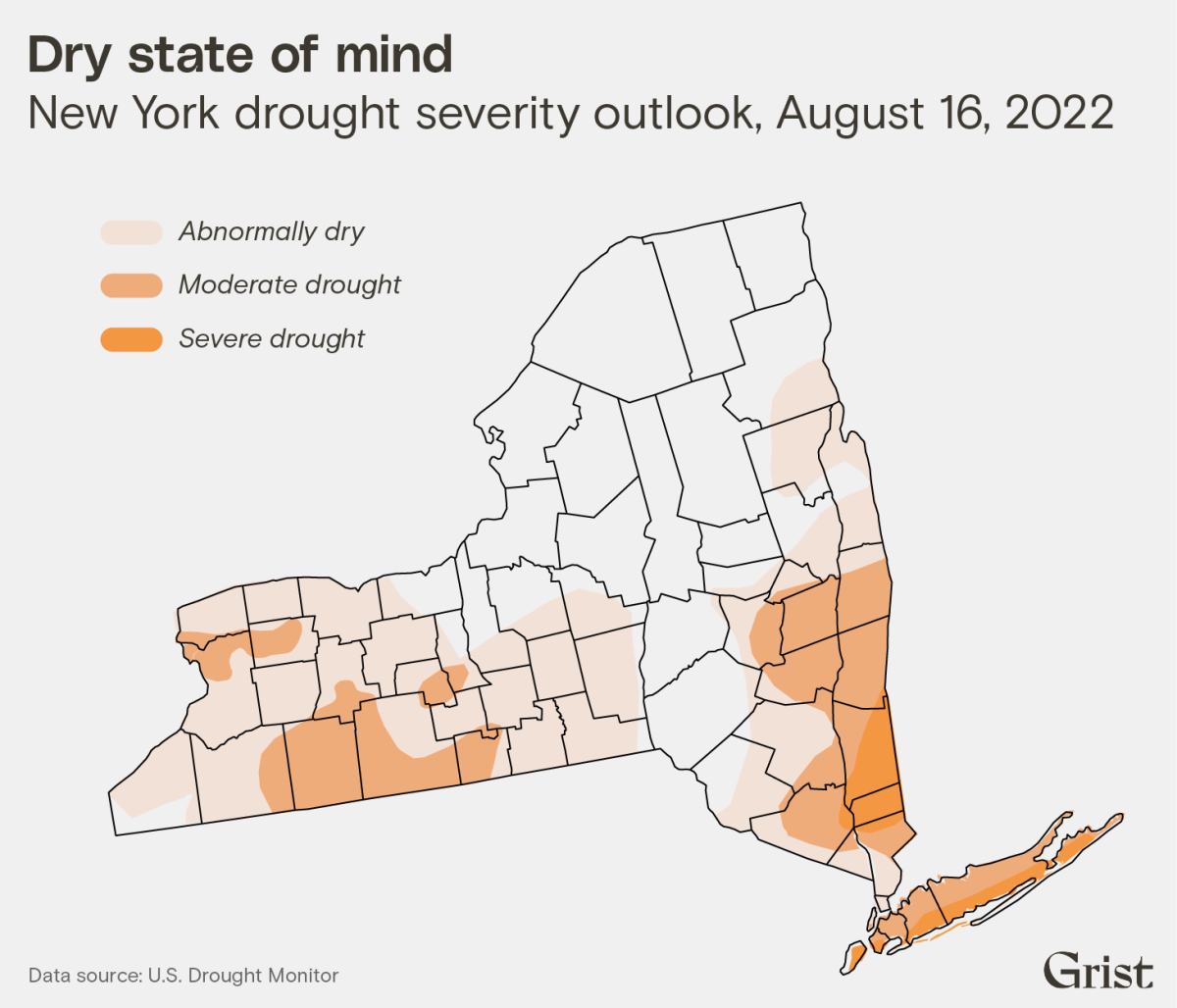

According to the latest federal drought maps, sections of Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts are in “extreme drought,” while parts of New Jersey, New York, New Hampshire, and Maine are in “severe drought.” On a visit to upstate New York this weekend, I noticed corn fields full of brown, brittle stalks, lawn after lawn of desiccated grass, and lakes and ponds with strikingly low water levels. Signs of what I took as early autumn were actually trees turning brown from thirst. Meteorologists don’t expect the Northeast, which has been drying out since late spring, to return to normal until later this year.

A map of New York State illustrating drought severity as of August 16, 2022. The southern part of the state is experiencing moderate-to-severe drought. Grist / Chad Small / Clayton Aldern

The situation, scientists say, is the latest example of a burgeoning and climate change-driven phenomenon known as flash droughts — rapid onset, short-term droughts.

“This year, what’s been the most shocking to me as a scientist is how quickly areas with relatively high soil moisture in the spring have shifted into not only drought but pretty severe drought,” Zachary Zobel, a scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center in Massachusetts, told Grist. “New England is a good example of a place that was pretty dry in the spring but certainly wasn’t predicted to reach severe drought in just the span of a few months.”

Flash droughts are caused by a drop-off in rainfall that occurs at the same time as a spike in surface temperature, which leads to soils significantly drying out. Recent research shows rising global temperatures may be causing flash droughts to take hold faster. In regions already susceptible to rapid onset droughts — places like South Asia and central North America — flash events that come on in just five days have increased by 22 to 59 percent.

The Northeast’s farmers may bear the brunt of this year’s dry spell. Cranberry farmers in southern New England, who grow their product in water-dependent areas such as bogs, could be particularly impacted. So could growers of other region-specific crops, like apples and sweet corn.

The low public water supply reservoir in Scituate, MA John Tlumacki / The Boston Globe via Getty Images

Chad Small, a recent data fellow at Grist, published a story today about a family-owned orchard in upstate New York that has been trying to adapt to shifting growing conditions in the region. One thing that’s worked for that farm? Drip irrigation, a water delivery system invented in Israel that sends a constant tiny drip of water to the base of plants throughout the day instead of a large helping of water in the morning and evening. Without drip irrigation — something typically utilized by farmers in more arid climates — extended periods of little rain “could outright kill the [apple] trees,” Gary Samascott, who runs Samascott Orchards in Kinderhook, New York, told Chad. Such measures hint at something folks across the U.S. will have to do more and more as the climate changes: adapt to new and unexpected environmental conditions.

What we’re reading:

The great drought and the great deluge, all at the same time

By Ishaan Tharoor, Washington Post

◆ Read more

Climate change led to dinosaurs’ demise. Now, drought reveals more of their tracks.

By Wynne Davis, NPR

◆ Read more

The fight against drought in California has a new tool: The restrictor

By Stephanie Elam, CNN

◆ Read more

California to install solar panels over canals to fight drought, a first in the U.S.

By Greg Cannella, CBS News

◆ Read more

Spain’s olive oil producers devastated by worst ever drought

By Mark Lowen, BBC News

◆ Read more