Here’s the latest installment in the great war between Tesla Motors and The New York Times, launched after a Times reporter chronicled a troubled test drive of Tesla’s all-electric sedan. For background, see here; for additional commentary, just turn on your computer. There have been dozens of posts on the subject, from the Times’ public editor, GigaOm, Gawker, MIT Technology Review, Jalopnik. But the place to start is where our previous piece left off: with a post on the Tesla blog responding to the Times’ claims, written by chair Elon Musk.

You may have heard recently about an article written by John Broder from The New York Times that makes numerous claims about the performance of the Model S. We are upset by this article because it does not factually represent Tesla technology, which is designed and tested to operate well in both hot and cold climates. …

When Tesla first approached The New York Times about doing this story, it was supposed to be focused on future advancements in our Supercharger technology. There was no need to write a story about existing Superchargers on the East Coast, as that had already been done by Consumer Reports with no problems! We assumed that the reporter would be fair and impartial, as has been our experience with The New York Times, an organization that prides itself on journalistic integrity. As a result, we did not think to read his past articles and were unaware of his outright disdain for electric cars. We were played for a fool and as a result, let down the cause of electric vehicles. For that, I am deeply sorry.

It is not clear for whom Musk feels sorry, but it is quite clear whose feelings have been hurt: his own. It’s clear in the emotion behind his post, emotion that he bolsters with nine bullet-pointed counterarguments, five graphs of data from the car, two Google maps, and one annotated graphic from the Times article.

The Tesla Model S, in a sunnier climate.

Those reading Broder’s review were given the impression of a vehicle not ready for the rigors of highway travel — if not of a vehicle that had a flawed power-management system. Both Broder and Musk suggest that the cold weather during Broder’s journey from D.C. to the Boston area reduced its range, but Broder suggests that the car failed to give him accurate information about that reduction.

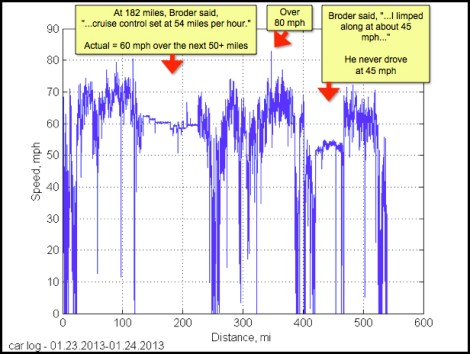

Oddly, this central premise is only a small part of Musk’s response — a response that, as the above-linked Gawker article notes, has been seen by many as definitive, a data-based refutation of Broder’s claims. After all, look at this chart:

Broder’s article claims he set his cruise control at 54; it was actually at 60. He said he was driving 45 on the highway; it was more like 53. At one point he exceeded 80 miles an hour! The impression you’re meant to get here is that Broder misled his readers into thinking he took extreme measures to avoid draining the car’s battery and still it failed. Nope, says Musk, pointing at the chart. His numbers were off!

What’s missed, though, is the implication of that data for an objective reader. Broder did set his cruise control at about 60 mph for about 100 miles. He spent another 50 driving at just over 50 mph. Almost all of Broder’s driving was on highways, as was intended in the test drive. Is it actually a win for Musk to show that Broder drove at 50-60 mph on the interstate instead of 45-54?

Musk’s post uses a common rhetorical tactic: overwhelming the audience with small refutations of unimportant points to give an impression of overall victory. The Atlantic Wire has a graph-by-graph breakdown of how strong and important each point is to Musk’s case; on the whole, they aren’t that important.

One commonly cited point from Musk’s post suggests that Broder drove in circles at a rest-stop charging station. “When the Model S valiantly refused to die,” Musk writes, Broder “eventually plugged it in.” Musk offers a graph that shows no circling, no distance, just faster and slower driving. Broder has already responded to this claim: He was circling the rest stop trying to find the charging station. The graph loses.

Elon Musk is a smart man. He understands the damage the Times review did to his company’s reputation. He’d hoped, as noted above, that the paper would report “on future advancements in our Supercharger technology,” those free charging stations that Broder tried to reach — not do a trial that Consumer Reports had already completed to his satisfaction. When Broder and the Times didn’t comply, Musk responded forcefully and, if the online sentiment is any gauge, successfully.

Even by the standards of Musk’s data, the problem lies with Broder’s experience, not his reporting. It’s not a driver’s job to make sure the car works perfectly; it’s Musk’s job, Tesla’s. The problem isn’t whether Broder spent 47 minutes charging the car instead of 58, as Musk ridiculously suggests; it’s that electric vehicles are competing with perceptions and infrastructure determined by traditional cars.

Broder is expected to release a response to Musk’s criticisms this afternoon. It will once and for all clearly settle who the winner is in this fight: gasoline.