USGS Gas Hydrates LabMethane hydrate burning in a laboratory.

It sounds like an addictive drug.

And that may become an accurate description for the frozen fossil-fuel deposits that go by the name “flammable ice.”

On Tuesday, Japan announced that it had tapped into flammable ice beneath the deep-sea floor and burned the methane that it contained. The achievement was a milestone victory in long-running international efforts to extract and burn the world’s richest source of untapped fossil fuels.

This frozen ice, or “fiery ice,” is a rudimentary material: methane, the main ingredient in natural gas, locked inside ice instead of inside rocks. Scientists call it “methane hydrate.”

From Bloomberg’s report on Japan’s announcement:

“Methane hydrates are everywhere, including in some of the fastest-growing economies,” said Will Pearson, director for global energy & natural resources at Eurasia Group in London. “If the technology is developed, it’ll alter the gas market. What is already the golden age of gas will last much longer.”

Within five years, Japan, which currently imports most of its fossil-fuel supplies and has shut down most of its nuclear power plants (at least temporarily) in the wake of the Fukushima meltdown, could be extracting and burning this new fuel on a large commercial scale.

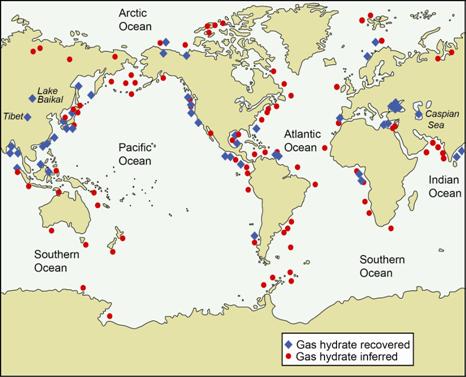

Given the vast reserves of methane that are locked up in permafrost, mostly beneath the sea floor — everywhere from the tropics to the poles, including a giant reservoir beneath Alaska’s North Slope — it’s inevitable that other countries will follow suit.

From a Washington Post primer:

How much energy are we talking about? Potentially, a staggering amount. The U.S. Geological Survey estimates that gas hydrates could contain between 10,000 trillion cubic feet to more than 100,000 trillion cubic feet of natural gas.

Some of that gas will never be accessible at reasonable prices. But if even a fraction of that total can be commercially extracted, that’s an enormous amount. To put this in context, U.S. shale reserves are estimated to contain 827 trillion cubic feet of natural gas. …

The U.S. Geological Survey estimates that there’s more carbon trapped inside gas hydrates than is contained in all known reserves of fossil fuels.

The material looks wonderful — if you put a match next to a cube of it, it will burn, creating the impression that pure ice could be used as a clean-burning fuel.

But this is no Harry Potter shit.

At the microscopic level, flammable ice is nothing more than a lattice of methane molecules embedded inside frozen water crystals. Get the methane out of the ice and, hey presto, you’ve got yourself some natural gas to burn. Natural gas is frequently lauded as a cleaner energy source, but only when compared with the dirtiest options, coal and oil. Really it’s just another climate-changing fossil fuel.

Until now, tapping into deep-sea frozen ice had been a pipe dream of many corporations and nations. Mining ice from beneath the ocean floor is not easy.

But the Japanese Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry announced Tuesday that a team aboard a drilling ship had successfully tweaked the pressure around a flammable ice deposit 1,000 feet below the seabed and thawed out the ice from around the methane. As described by The New York Times:

With specialized equipment, the team drilled into and then lowered the pressure in the undersea methane hydrate reserve, causing the methane and ice to separate. It then piped the natural gas to the surface, the ministry said in a statement.

Hours later, a flare on the ship’s stern showed that gas was being produced, the ministry said.

So, yippee, we’re one big step closer to burning a source of natural gas that’s cynically branded to sound even cleaner than the already cynically branded “natural gas.” Bust out the melting permafrost and take a celebratory sip, everybody.

USGSMethane hydrate deposits are everywhere.