The vision

“When you lose it, you’ve lost a record of climate on Earth that can never be recovered. There’s a lot of scientists who realize this, and have realized it for decades, who are making heroic efforts to recover this ice before it disappears forever.”

— Ice core scientist Tyler Jones

The spotlight

The first time Tyler Jones visited the National Science Foundation’s Ice Core Facility in Colorado’s Jefferson County, he felt like he’d stepped into an episode of The X Files. “It was like I was in some secret government installation,” he said. Jones, an ice core scientist from the University of Colorado Boulder, equated the facility to a “giant walk-in freezer” nestled inside an old concrete building, where scientists are preserving cylinders of glacial ice that essentially act as time capsules of information.

The coldest chamber of this immense freezer is filled with shelves bearing the weight of ice cores from both poles, stored in protective metal tubes, dating back decades. “It’s basically a giant library of ice cores,” Jones said — a library that includes some of the first ice cores ever taken.

Portions of samples from as far back as the 1950s are preserved at the facility, because scientists have long known that, as technology advanced, it would allow future generations to analyze old samples in new ways. “We always try to save some ice to give those future scientists a chance to do something better than we’re doing right now,” Jones said.

This desire to preserve ice cores has taken on a new urgency, given how fast glaciers around the world are melting. When the average person thinks about this problem, they may picture icebergs falling into the sea and mountainsides left barren as the ice retreats upslope. But glacial melt is also having an invisible impact within the ice itself, rapidly erasing the data that glaciologists and climate scientists rely on to learn about planetary changes.

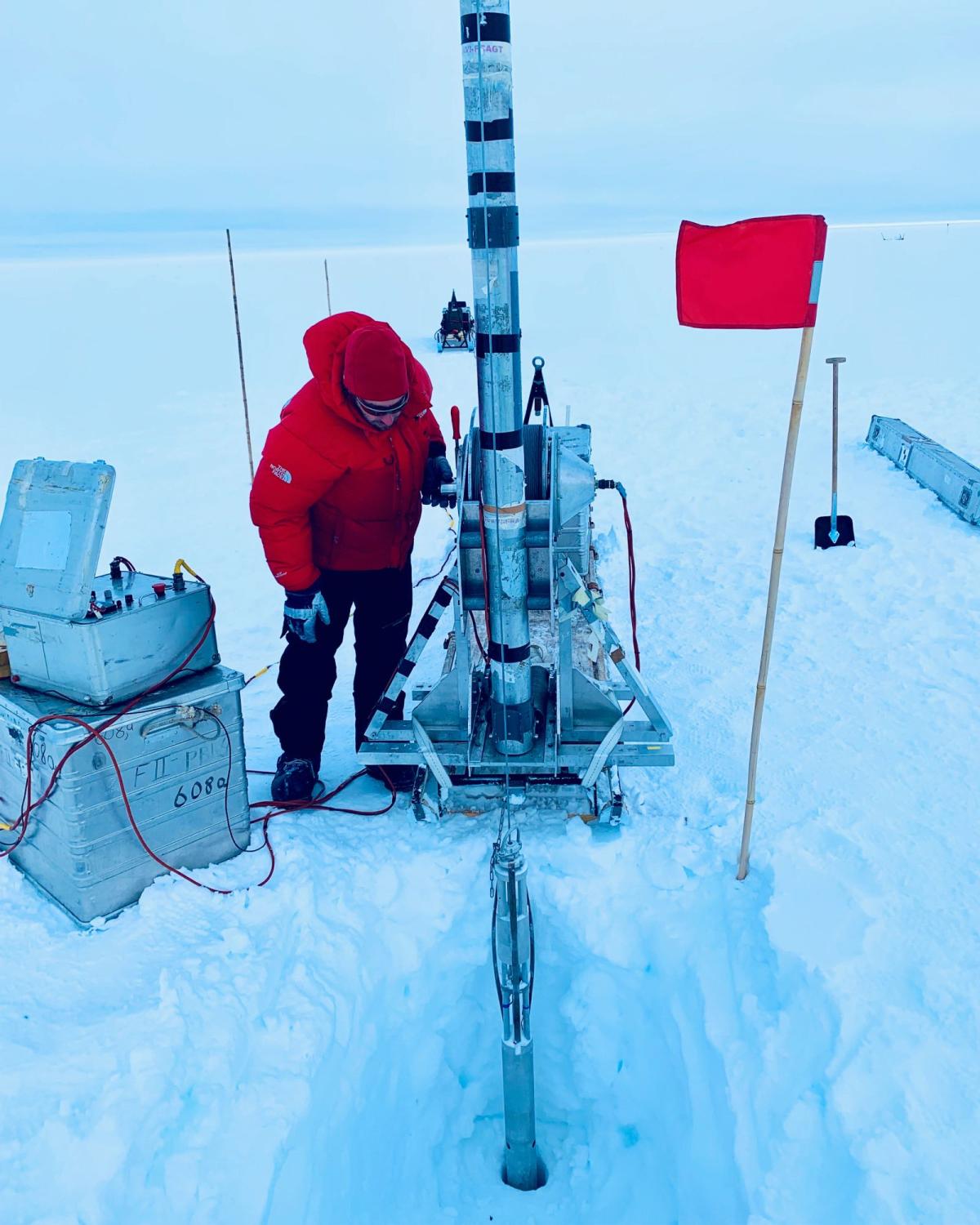

A piece of an ice core extracted by a research team in Svalbard, Norway. Riccardo Selvatico for CNR and Ca’ Foscari University of Venice

Around 10 years ago, Carlo Barbante, a chemist at the University of Venice in Italy, and his glaciologist colleague Jérôme Chappellaz from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology had the idea for an initiative that would complement the work of the Ice Core Facility in Colorado and similar facilities in other countries: an international Ice Memory Sanctuary, focused on preserving cores extracted from endangered glaciers.

The sanctuary was built last year as a cave on the High Antarctic Plateau, where the average temperature is -54 degrees Celsuis (-65 degrees Fahrenheit). So far Barbante, Chappellaz, and their colleagues have collected cores from seven glaciers across Europe and one in Bolivia that will eventually be stored there, and they have plans underway for more international collaborations to add cores to the sanctuary from other parts of the world.

“We don’t want to lose these important archives,” Barbante said. “They give us a lot of information about, of course, the past, but also the present and the future.”

![]()

Andrea Spolaor remembers how far out the front of a tidewater glacier reached when he first visited the world’s northernmost research station in Svalbard, Norway, more than 10 years ago. He estimated that it may have retreated by nearly 2 miles since then. In April 2023, when Spolaor, a snow chemist with the Italian Research Council, led an expedition to take a core from an ice field 25 miles away from Ny-Alesund station, melting already posed a problem.

When he and his team reached their chosen location, they set up their drill and got to work carrying out their plans to extract two 400-foot-long ice cores. But after about 80 feet, they pulled up water. At first, they tried to drain what they thought was a small pocket of melt. “After, I don’t know, five or six hours,” Spolaor said, “I think we took out three or four hundred liters of water.” They’d struck an aquifer. In 2005, a research team had drilled through solid ice in that same spot.

Spolaor and company moved uphill to try again. It meant thinner ice, but they still managed to take three roughly 240-foot cores without striking water again.

Then time came to pack up the samples, strap them onto sleds behind their snowmobiles, and head back to the research station. As they neared the coast, they discovered that a river of meltwater had formed while they were draining aquifers and taking cores. They had no choice but to wade through 100 yards of ice-cold, waist-high water to carry each box out. “It was a bit annoying,” Spolaor said. “We spent four hours in the water to take out the samples.”

Spolaor’s team’s research camp on an expedition on Svalbard. Riccardo Selvatico for CNR and Ca’ Foscari University of Venice

Spolaor and his team plan to use a portion of the samples for their immediate research needs, building on studies they’ve done in the past to understand what the future holds for Svalbard and other places in the Arctic. They’re hoping that the lower portion of their ice core will cover an era of unexpected warming that took place around 1,000 years ago, which has the potential to tell us something about how the poles respond to abrupt warming. The samples they don’t use for research today will head to the Ice Memory Sanctuary for other research teams in the years and decades ahead with questions of their own.

![]()

As snow accumulates on a glacier, it slowly crushes and compacts what lies below it. The snow transitions first into a porous substance called firn, before getting squeezed all the way into ice. But the pores don’t disappear. The ice is full of tiny air bubbles. “This makes the ice an absolutely unique archive,” said Margit Schwikowsi, an environmental chemist and chair of the scientific committee for the Ice Memory Foundation, the organization that was established in 2021 to create the sanctuary. The bubbles offer a glimpse of ancient atmospheres. “There’s no other archive, to my knowledge,” Schwikowski said, “where you have this direct preservation of old air.”

The archives they carry allow ice cores to serve as historical records printed in the form of molecules and aerosols. The cores are filled with stories of eruptions, wildfires, storms, plastics, and, of course, climates. Oxygen isotopes tell scientists about global temperatures at the time the ice formed, while the air pockets reveal what greenhouse gases were present in the past. But, as Spolaor and Schwikowski have both encountered in their own investigations, runoff from melting glaciers can erode or entirely erase some of those climate signals as meltwater trickles through the ice crystals. And it can happen quite suddenly.

This past January, both Spolaor and Schwikowski published studies independent of each other that had similar conclusions for different glaciers: In just a few years, melting had eroded a substantial portion of the climate record the glaciers had once contained.

Though the papers by Spolaor and Schwikowski are among the first to document this loss as it happens, scientists have long known this was a possibility. Glaciers have been melting rapidly for decades, and there’s a chance we’ve already hit a tipping point that would cause them to continue to disappear even if aggressive climate action is taken.

With those concerns growing, some experts are also considering more targeted measures to protect the world’s glaciers. Earlier this month, a group of scientists released a first-of-its-kind report calling for a “major initiative” over the coming decades to study techniques that could slow, halt, or even reverse the melting of glaciers and mitigate the associated rise in sea levels. One example is some form of underwater curtains that would insulate ice shelves from warmer ocean water. Scientists and advocates still have hope that these types of interventions won’t be necessary — but, as with the Ice Memory Sanctuary, it’s a form of insurance to at least investigate these possibilities now.

![]()

A lot of work remains to be done for Barbante, Schwikowski, and their colleagues, including finalizing a scientific steering committee to evaluate proposals for using ice cores from the sanctuary, with an eye toward one day handing the foundation over to a large international body like UNESCO that has the resources to manage this scientific treasure trove.

The more immediate challenge is finding funds to conduct the expeditions, and convincing their international colleagues to take on the logistical complications of gathering an extra sample or two to send to Antarctica — which can mean increasing the risks of expeditions that are already complex and hazardous. But many researchers are willing to take on the risk for the sake of ensuring future generations will have access to the same crucial information that fuels their own studies.

“When you lose it, you’ve lost a record of climate on Earth that can never be recovered,” Jones said. “There’s a lot of scientists who realize this, and have realized it for decades, who are making heroic efforts to recover this ice before it disappears forever.”

— Syris Valentine

More exposure

- Read: more about the latest science on glacial tipping points (Grist)

- Read: a personal essay about what it meant for Venezuela to lose its last glacier (The Washington Post)

- Read: more about the underwater curtain method that could protect glaciers from hotter oceans (The Guardian)

- Watch: a short video explaining how the ice cave was designed and built to house the sanctuary in Antarctica (Ice Memory Foundation)

A parting shot

A photo of how ice samples are extracted. Here, glaciologist Tobias Erhardt drills a shallow ice core at the East Greenland Ice-core Project camp.