When I was in high school, I used to walk around Pittsburgh at night a lot. It wasn’t really a matter of defiance or anything like that — it was just what made sense. Buses were inconsistent and unreliable after about 8 p.m., I didn’t drive, and any of my friends who did were usually too drunk or high to count on for a ride when it was needed. As a result, I frequently ended up walking home from parties, sometimes up to three or four miles.

Most of these times, I was alone. I liked being able to leave parties on my own terms, and finding my way home on foot turned into a more or less weekly ritual, during which I could process the abundant angst of my teen years. I never felt endangered or threatened. To the contrary: Those hours at night, around 1 or 2 in the morning on quiet, cold, intermittently spotlit streets, made up the few times in high school in which I remember feeling calm. I didn’t just feel like I owned the city — I could convince myself that I was the only person in it.

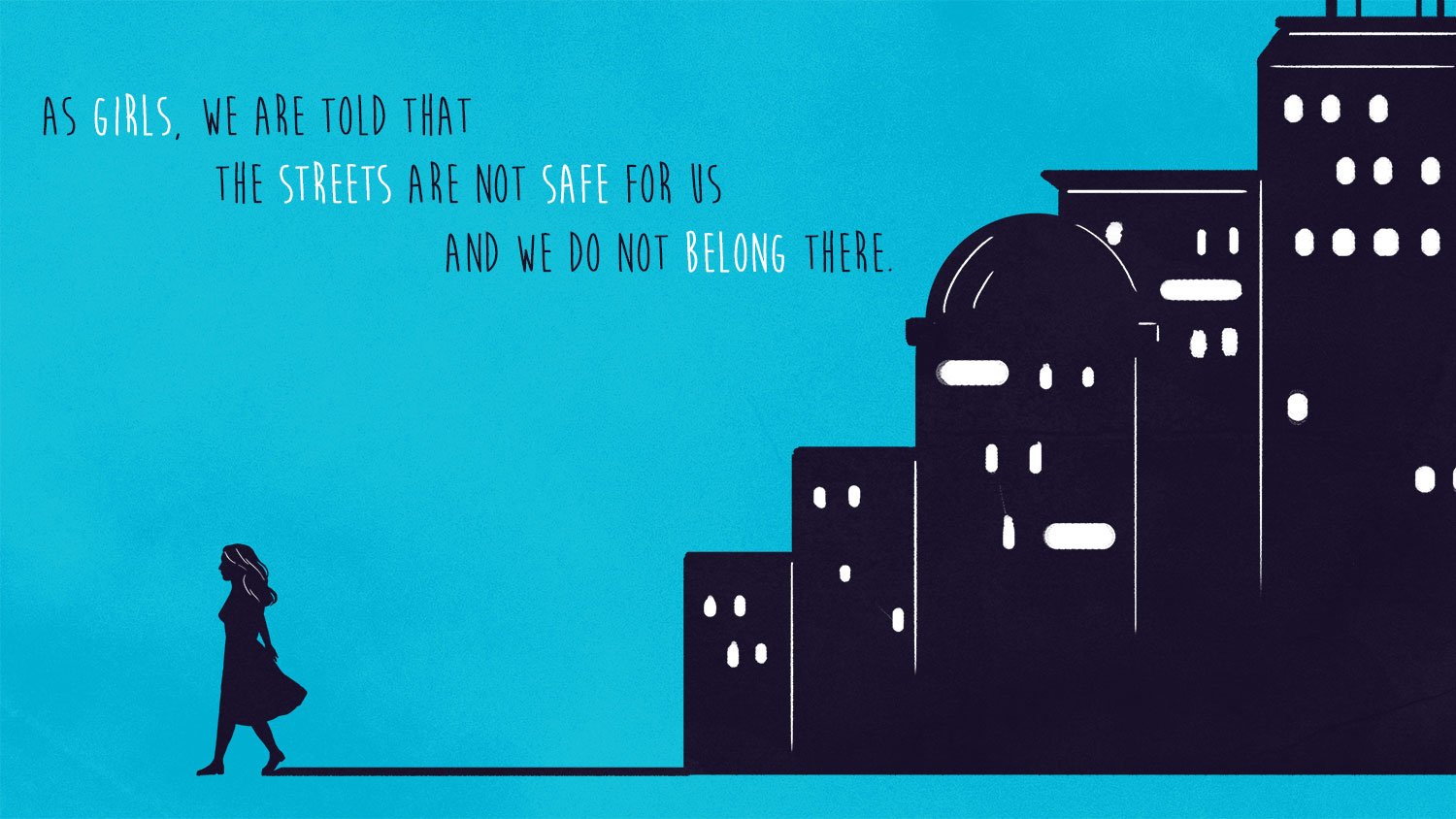

As girls, we are told again and again and again that the streets are not safe for us and we do not belong there. Last winter, my colleague Darby Minow Smith wrote a lovely piece on the experience of walking alone at night — and how as women, we can be scared to participate in our own communities because we have been taught to feel unsafe in them. The mantra is that to be alone in a city at night is to put your body at risk. As it turns out, the riskiest situation my own body ever ended up in was in a friend’s bedroom at a party, incapacitated by a Solo cup’s worth of terrible vodka. I was 16, and while all the adults in my life had urged me repeatedly not to be outside alone after dark, no one had ever warned me about that.

That blurry and awful night was, quite sadly, not an exception to the rule — far from it: The Center for Disease Control’s most recent statistics on sexual assault show that only 12.9 percent of rapes are perpetrated by a stranger, while 45.4 are committed by an intimate partner and 46.7 by an acquaintance. (If these numbers aren’t adding up, it’s because women were able to report multiple instances of sexual assault in this survey.)

So while we often see cities and streets as threats to our well-being, the real threat — a culture that teaches us that women’s bodies are for consumption, even when those women are friends and wives and girlfriends — is far more insidious. It changes the lives of women like Daisy Coleman, Emma Sulkowicz, and the much-maligned Jackie from the UVA case disastrously covered by Rolling Stone.

Our public understanding of what the word “rape” means has finally begun to evolve to acknowledge this reality — but honestly, not quickly enough. The FBI’s official definition changed in 2013, which was a monumental move toward accepting the idea that a woman who can’t consent to sex — whether she is intoxicated or unconscious — is still a victim of rape, regardless of whether she has been physically restrained or attacked with a weapon:

The old definition was “The carnal knowledge of a female forcibly and against her will.” Many agencies interpreted this definition as excluding a long list of sex offenses that are criminal in most jurisdictions, such as offenses involving oral or anal penetration, penetration with objects, and rapes of males. The new Summary definition of Rape is: “Penetration, no matter how slight, of the vagina or anus with any body part or object, or oral penetration by a sex organ of another person, without the consent of the victim.”

A 2010 study by Louise Ellison and Vanessa Munro, from the University of Leeds and University of Nottingham, respectively, examined how widely perpetuated, and largely false, understandings of what constitutes “real rape” can affect how jurors prosecute an accused rapist.

“Real rape” is constituted by a sudden, surprise attack by an unknown, often armed, sexual deviant. It occurs in an isolated, but public, location, and the victim sustains serious physical injury, either as a result of the violence of the perpetrator or as a consequence of her efforts to resist the attack […] In actuality, the majority of rapes are perpetrated by an acquaintance or intimate, that private spaces—including the victim’s home—are as dangerous as public ones, and that many women who are raped do not physically resist or suffer significant bodily injury.”

And sure enough, Ellison and Munro found that a sample jury would be less likely to convict a rapist who had attacked an acquaintance in a familiar setting, based on the preconception that a rape must involve a struggle, a weapon, or a psychotic stranger. There is the harmful and pervasive idea that if it really were a rape, the woman would have yelled more, or struggled, or tried to fight back harder.

A brief reminder: None of this is at all meant to imply that the attacks we are taught to fear, those committed by strangers in dark alleyways, do not happen at all. They do, and they are atrocious and they are life-changing. But so are the rapes that happen in college dorms, friends’ houses, and married couples’ bedrooms, though of course we are not warned to avoid those places.

The easy takeaway is that women aren’t safe anywhere — everywhere is dangerous and awful! But that’s a counterproductive approach, as Annie Gebhardt, Training Specialist with the National Sexual Violence Resource Center, explained to me. The sexual assault advocacy and education community has worked to shift our tactics for avoiding sexual violence away from warning women against potential danger, and more toward addressing why sexual assault happens.

“There’s a long history of so-called safety tips targeted particularly towards women that are really based in a lot of myths about sexual violence, and where and when and why and to whom it occurs,” Gebhardt says. “And often, those messages of, ‘Don’t walk alone,’ ‘Don’t wear this,’ ‘Don’t go here,’ have one, really limited women’s freedoms to be in the world, and two, placed the responsibility for sexual violence and preventing sexual violence on potential victims instead of placing [that] on perpetrators — and placing responsibility for preventing sexual violence on the entire community.”

Not only do risk reduction methods, as they’re called, make women beholden to preventing their own rapes, they’re also not that effective. Which is why, as Gebhardt says, sexual assault training today focuses on changing a system that normalizes sexual violence and misogynistic attitudes.

“Within prevention, there’s much more of a focus on teaching everyone in the population about things like healthy sexuality, and being a responsible bystander and speaking up when you see either a potential dangerous situation unfolding, or when you encounter jokes or comments or myths that could reinforce cultural norms that support sexual violence.”

To address sexual assault on campus, for example, new education campaigns like the White House initiative “It’s On Us” or the Canadian campaign #WhoWillYouHelp focus on educating students to intervene when they see a potentially bad situation in progress — an approach that takes into account the fact that perpetrators of sexual assault, particularly in college settings, are usually intoxicated themselves. To enable franker and more constructive discussion of sex, both Ontario and the U.K. are introducing sex-ed curricula for public schools that include discussion of consent.

A sustainable city, ultimately, is one in which women feel safe. But we should not feel safe because, as my teenage self did, we can pretend we are alone when the streets are silent and empty. We should be able to feel safe because we can believe that the other people who inhabit those streets are not only not trying to hurt us, but also are working to create an environment in which women are not seen as prey. Everyone in a community is responsible for changing the kind of thinking that would lead a man to see an unconscious body, or a girlfriend who is clearly saying “stop,” or a friend who has had too much to drink, as a fair sexual partner.

I’m not nearly naïve enough to believe that, with a snap of my fingers and some well-executed education campaigns, sexual violence will be eradicated tomorrow. But failing to change prevailing, harmful attitudes toward sex and women is a bit like ignoring rising sea levels: To do so is to willfully endanger a huge segment of the population. And to keep doing so, to keep refusing to recognize that endangerment, is to make life for everyone on the planet just that much uglier and sadder — and, really, no one needs that.