Kramer Wimberley is lying on the bottom of the sea. Thirty feet under, facedown against the white sand, he makes a stark black cutout in the shadow of the boat tethered above. The rest of the divers — a group of teenagers and adults participating in a volunteer scuba program in the Florida Keys — are already drifting toward the surface, attention fixed on the dive computers strapped to their wrists. But I am watching Wimberley, who seems so relaxed he might be asleep. If I watched carefully, I could see him breathing, slowly, in and out. Each intake lifts him a degree off the sand; each exhale sinks him down again. He is the last one of us to get out of the water.

When I ask him later what he was thinking about down there, he just said, “That’s my home.”

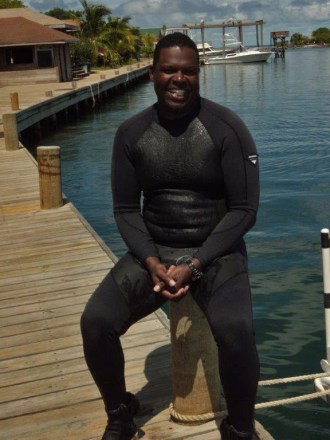

A dive instructor, Wimberley, 51, has spent more of the last 30 years of his life underwater than, well, more than the rest of us probably spend doing anything other than sleeping. He’s toured the world’s submerged sights, from the heavily trafficked Keys to the pristine reefs of the South Pacific, and has seen firsthand the kinds of effects humans are having on the oceans — some of his work involves finding ways to restore damaged ocean ecosystems. He’s also the rare African American in the predominantly white world of diving.

[grist-related-series]

Wimberley’s real passion is for teaching people to join him in his element, especially would-be divers who might not feel at home in the water right away. “People who may end up walking away from it because they had a bad experience, those are the people I target,” he says. As a member of the National Association of Black Scuba Divers — and in a country where, for a whole slew of ugly reasons, 70 percent of black kids reportedly don’t know how to swim — Wimberley is no stranger to people who’ve had bad experiences with water. And let’s face it: Spending an hour under a couple atmospheres of pressure, breathing from a tank and hovering above the abyss — that can be a scary proposition for anyone.

He’s calm, he’s patient, and he knows how good it can feel to find your water legs. “I think everybody should be in the water, underwater,” he says. “That’s where I live.”

Here’s some more (edited and condensed) of what he had to say:

The first time he got underwater

My first time in the water was in Bermuda. I was on vacation, and at the time I was just going for a walk. I happened to be passing by a picture window, and I stopped to take a look at the picture. A gentleman popped out and asked, “Do you want to do that?” I didn’t know what he was referring to, so I said, “Do what? I’m just looking at a picture.” He said, “Well, what’s in the picture?” “Water.” “What else do you see?” And I’m like “Ohhhhhhh.” And he said, “Yeah, ‘ohhhh.’ Do you want to do that? I can have you doing that in like 15 minutes.”

So I went into the shop and he fitted me for some equipment, then he started putting the equipment on the boat. I said, “Isn’t there some kind of class you’re supposed to take for this?” He said, “I’ll teach you everything you need to know on the way out.” Well, OK. So we jumped on the boat, and off we went.

So I went into the shop and he fitted me for some equipment, then he started putting the equipment on the boat. I said, “Isn’t there some kind of class you’re supposed to take for this?” He said, “I’ll teach you everything you need to know on the way out.” Well, OK. So we jumped on the boat, and off we went.

We got to the site and he started putting the equipment on me. I said, “What happened to the class?” He said, “You don’t really need a class. You just do this, you do that, and we’re diving.” At that point, I had the equipment on me, I’m standing on the edge of the boat, and I’m thinking, “This is not good.” But before I could panic and call the whole thing off, he just pushed me into the water.

Once I got my head a foot below the surface of the water, I was hooked. I could see for over a hundred feet, it was crystal-clear, blue — there was a serenity attached to it. And then I saw fish, and I knew right then that this was what I wanted to do with the rest of my life. And that’s where it began.

Diving while black

The vast majority of the time, when I began diving, I would be the only person of color on the dive boat. Which was challenging, because everybody else on the boat was looking at me as if, ‘What are you doing here? You can’t swim, and you surely don’t know how to dive. And, OK, let’s hurry and buddy up so no one gets stuck with the guy who we already know can’t swim and can’t dive.’

[This happened] over and over and over and over again. I thought it was quite possible I was the only black diver in the world, because I had never seen any.

And then, back in 2003 or 2004, I was in Cozumel diving, and I saw a group of three African Americans walking down the street in front of me. They appeared to be talking about diving. And I was like, is it possible? So I stopped them and said, “You guys know about diving?” They said, “Of course. You’re not here for the summit?”

One guy said he’d been diving for 40 years. I’m like, “That’s not possible! I’m the only one!” They said, “Nope, we’re here for the summit — the National Association of Black Scuba Divers summit. We’ve got a couple of hundred black divers here.” I was amazed. They walked me down to the hotel where they were staying, and there were black divers on every boat, taking up just about every boat on the island. I’m like, “Wow, OK. I’m not the only one.”

Being visible

I swam competitively in high school, but I didn’t finish on the high school team because, again, it was just like being on a dive boat: I didn’t belong. So I was on the team for about a month, and it was apparent — back then, at least — that I wasn’t welcome. So I just went down to the city pool and swam by myself.

But that’s the beauty of being able to see someone who’s already doing [something that seems off-limits]. ‘Well, OK, if they’re doing it then it’s OK.’ So I’ve tried to stay as visible as possible so that — not just children, but adults also — can see that it’s OK.

Should [NABS] be more visible? I think so. But I would like — and this is personal — I would like for NABS never to have been in existence, the need for it. A group of divers who could not find comfort on an average dive boat, or feel welcomed, so they had to find or form an organization such that they could feel comfortable in the sport of scuba diving.

Teaching moments

[I’m especially drawn to] the adults who don’t swim well or people who are actually afraid of the water because they have these tragic stories about how someone tormented them or they suffered some trauma related to the water, and as a result of that they stayed completely away from it. So that is a challenge for me — if it’s something that you want to overcome, I’m willing to work with you for as long as it takes to overcome that fear.

So we’ll go to the pool, and we’ll sit by the pool and talk. The next time, we’ll come and we’ll sit closer to the water; and the next time we’ll sit and put our feet in the water; and then gradually build up to overcoming the fear of the water. Sometimes it could take months. But once they have the gear on and they’re underwater and you see the light, the sparkle, in their eyes, like ‘look what I just did!’ — there’s a sense of reward, knowing that somebody is about to see the underwater world, and I played some small part in that.

Changing ocean

I have noticed substantial drop-off in the marine life all around the world. And I’ve traveled the world looking for a particular species — I’ve spent my entire life looking for whale sharks. After almost 30 years, I saw one for the first time. It used to be you’d get in the water and see schools of sharks. Now you can get out there and do an entire dive trip and not see one. I don’t know if it’s attributable to global warming, the poisoning that we’re doing to the oceans, the overfishing — there are a number of factors, but there is a significant loss. It makes you weep to see the drop-off, the overfishing, the trawling, where they just destroy acres and acres of coral.

A whale shark, at last!

It was a feeling of exhilaration. ‘Oh my god, it is actually, finally, happening. I am in the water with a whale shark — this beautiful, graceful creature.’ There was just a sense of awe for the entirety of the time that that experience was going on. And then after I got out of the water, having devoted so many years to reaching this particular apex, there was also a feeling of, ‘Well, what do I do now?’ There are no more worlds to conquer. This is what I had spent more than half of my life trying to do, to be in the water with this particular animal that I thought was just so awe-inspiring and graceful. And I’ve been redirecting ever since.

Now my thing is thresher sharks. A thresher’s tail is the same length as its body. I just think sharks are such beautiful animals, and they have such a bad rap. We’re killing them by the millions every year. I want to be able to see all that I can see before they’re extinct — because that’s where we’re headed if we don’t do something drastic to stop this.

Diving is bliss

It provides me with some perspective. Initially, it was, ‘OK, I do everything that I do on land so that I can get back underwater.’ So walking and sleeping is just a surface interval for me. But it has made me more of a tolerable person to be around. I’m not the easiest person to be around when I’m not in the water. When I’ve been out of the water for a little while, it’s … it’s apparent. My attitude is a bit short, or curt. But show me a picture of the water or ask me something about diving — and I light up.