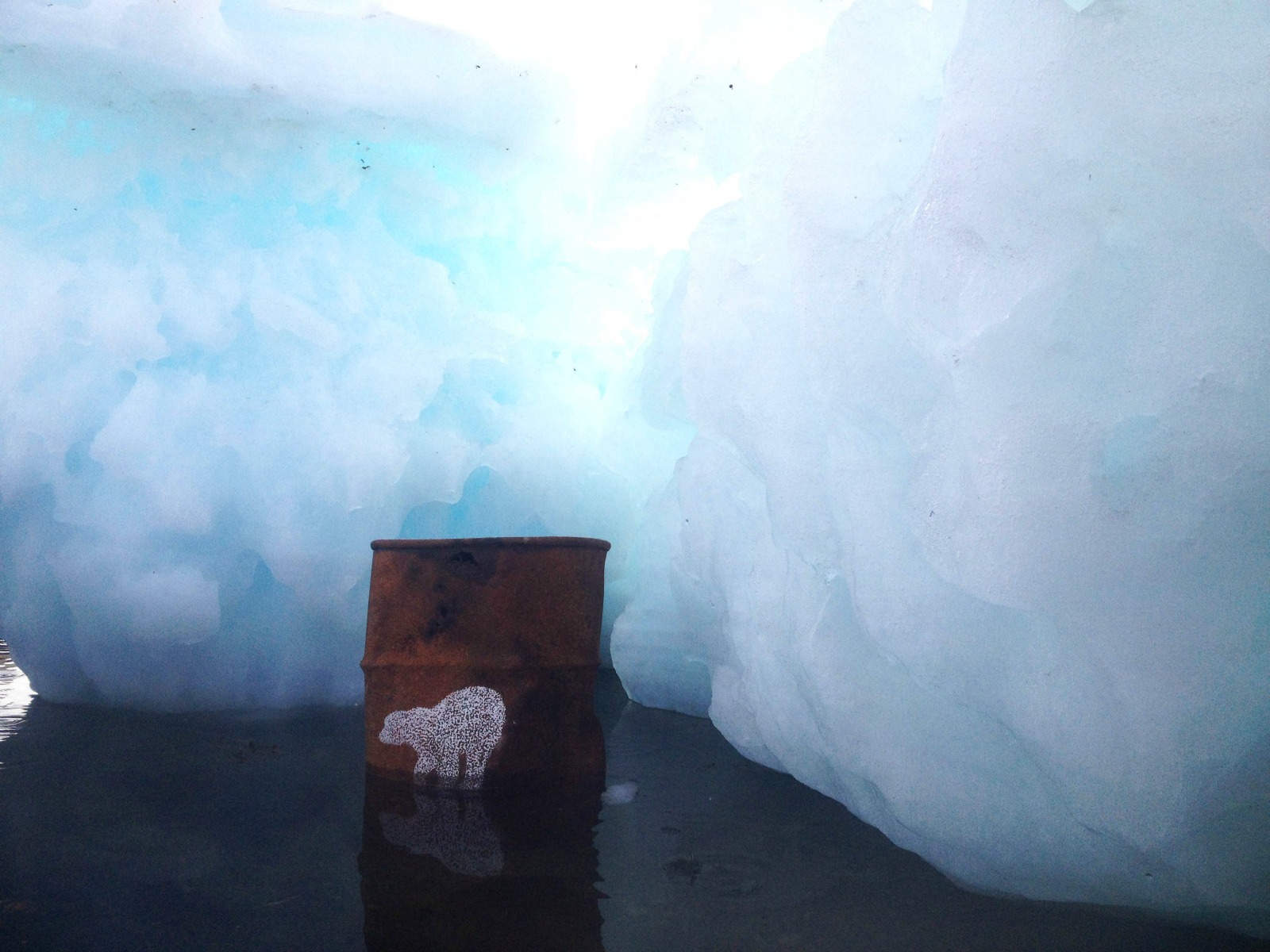

The silhouette of a polar bear, chalked onto a rusty oil drum, slowly sinks into the ocean against the backdrop of an iceberg. Standing waist-deep in frigid water, Julia Edith Rigby, an artist from California, snaps photos with her phone.

“Because the light was so diffused, it felt very cathedral-like in there,” she says. The tides come in, and soon, the barrel is completely submerged.

Bear Flood II Julia Edith Rigby

Rigby was living in Kulusuk, a small village on the east coast of Greenland, when she was struck by the beauty of the landscape — and the garbage on its shores. “There were a lot of oil drums, but also trash in general, because the village didn’t really have a system for taking away trash,” she said. “It just sort of glides into the ocean.”

Working with limited materials, Rigby would chalk an image on a dry drum on the beach and roll it closer to the water. She’d have 10 minutes, sometimes less, to take photos before the ocean would wash her drawings away: “It was this very temporary, very fragile, supposed-to-be-destroyed-at-the-end thing.”

Texaco Seals I Julia Edith Rigby

Rigby speculates that the oil drums she used for her series, “Greenland Drums,” may have come from a nearby American base abandoned after World War II.

She says that creating the art helped her process the changes happening in Greenland’s melting landscape and their impact on people and creatures alike. She chose to depict animals that were an important part of life for Greenlanders — polar bears, seals, fish.

Arctic Char Julia Edith Rigby

“I thought of them as installations in the landscape,” she says. “I liked how the tide was a part of the project, a collaborator, and the ocean got the final say.”

Melting Walrus I Julia Edith Rigby