Matthew Oswald’s house in the outskirts of Seattle’s Capitol Hill harbors a peculiar breed of chaos. “Everyday there’s something new,” Oswald says. “It’s like a sitcom.” Just think: Big Bang Theory meets The Real World.

Oswald is a bearded, tattooed, proud New Yorker who first moved to Seattle for a job as an Amazon engineer. Now the 34-year-old lives and works at the IO House, the first manifestation of GrokHome’s business plan to provide long- and short-term communal living to whizzes and geeks who are looking to break into Seattle’s budding tech scene. It’s Oswald’s job to keep the eight-person hacker house filled with fitting residents — described on GrokHome’s website as “smart people working on interesting projects” — and then make sure it all runs smoothly as they go about indulging in geekdom together. Some days that’s easier than others.

On one of the more interesting days, Oswald came home to find a Mack truck parked outside. It contained 20,000 pillowcases, all of which belonged to 22-year-old resident Jordan Schindler. The blossoming entrepreneur had come up with a zany product idea: pillowcases infused with acne medication, so teenagers could work on their complexions as they slept.

“Don’t worry, I think I sold them all,” Schindler assured Oswald. Sure enough, about two hours later another truck arrived, loaded them up, and carried them over to Amazon. “And they sold 20,000 units within like, I don’t know, less than two hours,” Oswald says.

Cooperative housing — a.k.a. co-living — has become a hot topic for anyone thinking about the future of urban living. In late 2013, the hype about co-living was in full force; tales of millennials packing into Bay Area buildings sprang up everywhere from Gawker to NPR and The New York Times.

In practice, co-living spaces generally take the form of group houses, with members renting a bedroom, but with an extra push to go beyond the ad hoc ensembles that come together through necessity via Craiglist. This might mean drawing housemates together around a particular set of ideals or pursuits, like the IO House. Or, more simply, it might mean that housemates agree to divvy up chores and enjoy communal meals together.

As rents skyrocket in major cities like Seattle, New York, and San Francisco, saving a few bucks by sharing a living space appeals more and more to otherwise priced-out young urbanites. And as a bonus for the green-minded, people who live in densely populated areas tend to have a smaller carbon footprint.

But as catchy an idea as co-living may be, for every co-living trend piece, you can find a data point that might suggest the trend is moving in the opposite direction, like the fact that more and more Americans are living alone. I’m a millennial, at least according to most definitions (and by the way, we “millennials” still aren’t feeling labels). I also helped form a co-living space in the Bay Area when I was in college. Reading all the recent hype, I wondered: Is co-living actually a big thing? A real cultural shift? Or just a clickable headline?

I set out to find some answers.

Giving co-living the business

One of the first things I learned was that co-living spaces — whether they’re labeled as “community houses,” “intentional communities,” or “hacker houses” — are popping up throughout the country. There are more than 186 North American groups listed in the Fellowship for Intentional Community’s directory. The nexus is decidedly in the crunchy and tech-oriented San Francisco Bay Area, where, according to The Christian Science Monitor, about 50 such homes currently exist.

OK, that’s hardly a world-shaking transformation. And communal houses aren’t exactly anything new: During the 1840s, the days of back-to-nature transcendentalism, at least 84 utopian communities popped up around the country. In the 1960s and ’70s, Boomers experimented with the commune, an idea that lives on today with retired hippies and Paul Rudd movies.

Still, there are some signs that what we’re seeing today is different, and in more than just name. For evidence, witness the handful of entrepreneurs who are founding co-living spaces in an effort to do what carsharing has done to car ownership (and cab companies and carpooling) — that is, disrupt the old economic model, transform city living, and make a buck at the same time.

Campus and OpenDoor Development Group (both in the Bay Area) and Krash (in Boston, NYC, and D.C.) all market themselves as hip, plugged-in communities for the smartphone-toting urbanite. Their websites advertise features such as month-to-month lease flexibility, high-speed Internet, and working space. Translation: These ain’t your daddy’s communes. They’re targeting millennials, who are said to value travel, job mobility, minimalism, flexible schedules, and social networks, and prefer cities to suburbs, stimulating work to high pay, and self-employment to the corporate ladder. Millennials are also said to be putting off marriage and children, ideals that sent previous generations of twentysomethings running for the ‘burbs.

Ben Provan and Jay Standish hatched the idea of OpenDoor Development Group, a company that buys real estate and turns it into co-living housing, when they were in the sustainability-focused MBA program at the Bainbridge Graduate Institute in Seattle. “We were basically studying the sharing economy and local economies and a lot of these new models emerging right now,” Provan told me. “And we got excited about how co-living and forms of community living could be a really powerful way to both live more sustainably and have a more generative and socially focused environment.”

What made their approach different from that of other group houses, Provan says, was treating it as a business — a business based on sharing resources. For example, OpenDoor would develop its own Airbnb-esque Modern Nomad software as a platform to host guests and stress carsharing via RelayRides. Most importantly, however, Provan and Standish saw OpenDoor as a business that facilitates other groups of like-minded people to connect and live together.

By the summer of 2013, Provan and Standish had acquired a property where they could test their vision — a house in Berkeley, Calif., which they called the Sandbox. Now all they needed were people to fill it. They put out a call for applications. Within two weeks, they had far more applicants than they had rooms. “It was a really fun process to create a community, and to realize that this was something that people wanted,” Provan said. “There was a need for a company that could help make that process easier for people and could help facilitate more of these spaces coming into being.”

Co-living (and coworking) at the Sandbox in Berkeley.

The Farm House, a 16-bedroom Victorian, also located in Berkeley, is the third and newest of OpenDoor’s acquisitions. If you lived there, coming home at night you’d walk past the vegetable garden (compost bin included) and into the spacious, hardwood-floored living room. This opens up into the dining room, where you’d likely be greeted by a subset of your 16 housemates sitting around the dining room table, applauding you — a house tradition. “It’s silly, but it’s really funny,” Farm House resident Gina Giarmo says. “It kind of puts life into perspective.”

Continuing on into the kitchen, you’d see it stocked with giant bins of rice and garbanzo beans — some of the oft-used dinner ingredients residents take turns cooking four or five nights a week. You’d share these meals with your housemates, who range in age from 23 to 38 and in profession from yoga instructor to startup geek.

Hangin’ at the Farm House in Berkeley.

Giarmo says a lot of the current residents had reservations about cooperative living at first, “because it has this stigma of being very dirty and disorganized.” But Farm House residents are like-minded in their approach to housekeeping, too. Housemates all pitch in with weekly chores, resulting in what Giarmo feels is a well-kept, welcoming space.

The Thanksgiving effect

Then there’s the issue of sustainability — an important part of the conversation to us here at Grist. To some co-living enthusiasts, such as Provan, living lightly is implied in the mission: Smaller space equals less stuff.

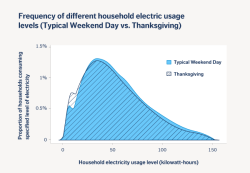

But what actually makes living communally greener? Well, part of the answer builds on the influx of people to cities. Some studies show that densely built urban areas have lower energy requirements than suburban sprawl. But these studies are scant, as is data on the carbon footprint of co-living. However, the patterns of U.S. energy use on one special holiday may give us a clue: Thanksgiving.

What’s Thanksgiving all about if not celebrating the oldest form of co-living: cramming a bunch of family members under one roof for a day. Centralizing people on Thanksgiving creates an energy outcome that’s almost as sweet as pumpkin pie: U.S. residential electricity and natural gas use drops by as much as five to 10 percent. Apparently, groups of people cooking, consuming, and living together use energy and resources more efficiently.

Graph from Opower

Of course, some co-living groups take sustainability to a whole other level. Dancing Rabbit Ecovillage, a 70-person, 280-acre community, is situated in the rolling hills of Missouri and, admittedly, is more bucolic commune than urban cohouse. Six idealists founded Dancing Rabbit in 1991 to create the “ultimate in green living.” The community’s website has a thorough breakdown of sustainability guidelines as well as a list of eco-commandments — “At Dancing Rabbit, fossil fuels will not be applied to the following uses: powering vehicles, space-heating and -cooling, refrigeration, and heating domestic water.”

My friend and former housemate Brian wanted to take the cooperative living thing to the next level and spent a summer in Dancing Rabbit’s work exchange program. Turns out this brand of green living was a little overwhelming for him. After all, building your own living quarters and growing all of your own food is not for the casual coliver. At least for now, Brian feels more at home in the eight-person co-op in Berkeley called The Nookery, where he now lives. He says while he’d like to live somewhere where sustainability is part of the equation, he’s not sure if he wants sustainability to be the whole of it.

Co-living as life hacking

In 2010, after spending two years living in Stanford University’s hippie refuge called Synergy (no kidding), a group of us from the campus co-op scene started a co-living house in Palo Alto. We eventually named it Ithaka. A year after Ithaka formed, New Yorker writer Patricia Marx paid us a visit. She was working on a piece about couch-surfing. We gave her a tour, which she described this way:

Come, let me show you around. This is Ellery’s room, but Ellery sleeps on the porch. Here’s the lounge. Here’s a bathroom. One thing you need to know about the bathroom: if yellow, let mellow. … Here’s Dan’s room. His girlfriend is Rachel; she doesn’t live here anymore, but she’s staying here now. … We call this room AbunDance. Mostly we dance here. … See the hula hoop, the beanbag chairs, and the bearded fellow smooching on the floor with the pretty, long-haired woman who’s wearing a shawl? This is Jonas. He doesn’t live here. He lives in a co-op in Berkeley called Fort Awesome. His sweetheart is Lena. She’s been on the road for two years, but right now she’s camping in the yard out back. … Here’s the puppet theatre. A lot of couch surfers stay there. If you don’t want to sleep in the puppet theatre, you can have Jan’s room and he’ll sleep with Tess.

OK, fair enough. But then the way Marx goes on, in my humble opinion, misses the point: “Has our relation with machines made us feel so deprived of human contact that we befriend anyone and shack up with whoever has a mattress?” she wrote. “People, it seems, are becoming fungible, and, as in a game of pinball, you score points by bumping up against as many of them as possible.” Well! For me, living in an intentional community wasn’t about racking up social pinball points. It was about meaningful human connection, IRL.

The rabbit holes of technology do play a role in co-living’s appeal. Technology does enable sharing and modern day nomadism on whole new levels, but “it’s also made us more isolated in many ways, and siloed out,” says Chelsea Rustrum, author of It’s a Shareable Life.

And Marx may be right that such isolation is what’s causing millennials to create communities outside the pages of Facebook, Twitter, or Pinterest. As Balaji Srinivasan framed it in Wired, co-living takes those digital communities out of the cloud and puts them into a tangible, physical space. You don’t have to pop out for a latte every time you need a fix of casual conversation.

I’m still nostalgic about it: Hey, remember when you used to come home to a gaggle of friends hanging out in the kitchen, cooking you a delicious dinner? You lived where there was something new and interesting going on almost every day: someone experimenting with making soap, baking the perfect baguette, or painting a mural on the walls.

OK, maybe that’s just my so-called quarter-life crisis, and I’m looking back at the co-living experiment through a pair of rose-colored glasses. But on the other hand, co-living gave me something previous living situations hadn’t: structure. A lot of recent college grads get hit with the reality that they can no longer expect friendships, work, and life to be served up on a plate right in front of them. The “real world,” is, you know, real. In the throes of trying to figure out how to transition to adulthood, co-living is a way for young people to ground themselves alongside others at a similar stage in life. Ambiguity loves company.

And for the ambitious, co-living can even breed entrepreneurialism. Take the hacker house, which is the premise of the IO House in Seattle. It’s a segment of the co-living movement designed to give budding techies an affordable entry point into cities with startup scenes, and the chance to surround themselves with people who have similar aspirations. Jordan Schindler jumpstarted his quirky pillowcase business in a co-living space.

Another cool thing about the modern version of co-living is that you don’t have to be all in or all out of the lifestyle. “What we’ve seen is that people take what they do like about the [cooperative] living scenario, but then bring it into the 21st century using technology,” says Lauren Anderson, chief knowledge officer of Collaborative Lab. “So you can opt in or opt out of the parts that you feel comfortable with, rather than needing to be all completely in or all out.” Intrigued by the idea of co-living, but not ready to commit? Houses like the Farm House, the Sandbox House, or Embassy have options for shorter-term stays through couchsurfing or Airbnb. Want to tap into that kind of community but know that when you come home at night you really do just want to be alone? Drop by for a salon at Rainbow Mansion or The Glint. Want to network with other fresh Seattle techies but don’t want to have to deal with their mess? Join one of their dinner and demo nights.

How the current co-living movement will pan out remains to be seen. You don’t have to dig too deep into history to find communal living movements of yore that failed miserably. But if there’s anything that sets the current iteration of co-living apart, it’s this: Whereas the leaders of past utopias were focused on breaking away from society (“turn on, tune in, drop out”), modern co-living is more focused on incorporating the lifestyle into the broader world.

After talking with torchbearers of the co-living scene and musing on the time I spent living in an intentional community, I think there is something bigger to co-living. To a generation that’s less interested in single-occupancy condos or white picket fences in the ’burbs, co-living is a way to embrace, and take ownership over, the chaos of life in an increasingly scattered digital age.

Since I left Ithaka, I’ve bounced around between rooms I’ve rented in Santa Cruz, Monterey, Washington, D.C., and Seattle. And then there are my family stops in L.A., New York, and Boston. While I’ve gotten used to embracing a more pop-up, fluid sense of community, “home” has become a rather relative term.

Last year, my fellow Ithakans and I gathered for a reunion in Klamath Falls, Ore. On the drive out there with four of them, we had an epic, eight-hour conversation that bounced from women’s rights to death, gun rights, and free will, all in a mysteriously cohesive way. We didn’t agree on all of it. But we shared such a baseline of experience together that I still felt so comfortable, so at ease, and so loved.

It was 2:00 or 3:00 in the morning when we finally arrived. We sat around a picnic table and looked up at a sky that made me feel as if I were actually swimming in the Milky Way. Punch-drunk tired, someone started giggling. Soon we had all set off into laughter. It was the kind of laughter where you find your stomach tangled into knots, tears streaming down your face, you don’t even really know what’s so funny — but, oh, it hurts so good.

It was then that I realized where I was, even in a place I had never physically been before: home.