When I first saw the headline “Childhood Cancer on the Rise,” it triggered my journalistic salivary glands. Sad news, sure — but it could also settle an old debate, I thought.

Cancer rates have been edging up over the years, which gives some credence to the idea that our modern way of life — replete with bad food and new chemicals — is killing us. But the statisticians have largely answered that hypothesis: The reason more people are getting cancer is because we are living long enough to get cancer.

Which is why a rise in childhood cancer perked my interest. Pediatric cancer can’t be chalked up to longer lifespans. But my (OK, somewhat ghoulish) thrill faded as soon as I read the article under that provocative headline.

The steady increase in these cancers can be attributed to better diagnostics and better technologies. It is often difficult for parents to spot early warning signs in children as they appear to mimic other childhood illnesses.

Good news! It’s not that childhood cancer rates are rising; it’s that our ability to detect cancer is improving. It’s amazing how headlines and articles can go in different directions. In this case, though, neither was quite right.

When I read the actual study, I saw that things were a little bit more ambiguous. Pediatric cancer diagnoses have been going up .6 percent a year since 1975. And we really don’t know how much of that is the result of better detection:

It is possible that some of this increase may be due to changes in environmental factors. Improved diagnosis and access to medical care over time may have also contributed, as without medical care some children may die of infections or other complications of their cancers without ever being diagnosed.

In sum, this review of childhood cancer statistics tells us precisely nothing new. The reason I bring it up is that people are mentioning the study on Twitter, giving it the same spin I’d initially assumed:

- Childhood cancer is going up.

- It’s because there’s a toxic load in our food or environment.

The problem is that we don’t know if No. 1 is true. I’m very interested in No. 2 (and if you want a wonderful, levelheaded assessment you should read Florence Williams’ book Breasts), but we shouldn’t push the case beyond the facts. Unless we are damn sure what we are talking about, it’s an injustice to the kids with cancer to try to use them to build a case for any cause. We should be focusing on finding the actual causes of cancer, not rooting for one cause in the absence of evidence.

There are real consequences in jumping to conclusions. One consequence of our quick acceptance of the “cancer rates rising” narrative is that we’re not sufficiently skeptical of diagnosis. As Otis Brawley, the medical leader of the American Cancer Society, has pointed out, some of the cancers we’ve detected weren’t actually harmful, or weren’t actually there. People have been hurt, even killed, by treatment they didn’t need.

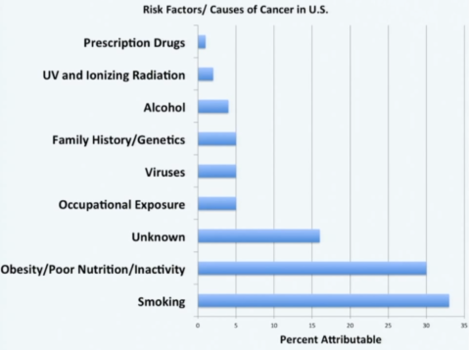

If we zoom out to look at all cancers, we already understand the causes of most, though there are still unknowns. Those causes turn out to be the usual suspects — the ones we should be working on now. I’m all for finding environmental causes of cancer, but let’s not be so anxious to pin the blame on one particular villain that we miss the real culprit.