Steve and Sarah EmryAntifreeze is a favorite of today’s poisoners, because of its sweet taste.

This episode of Inquiring Minds, a podcast hosted by best-selling author Chris Mooney and neuroscientist and musician Indre Viskontas, also features an interview with Quartz meteorology writer Eric Holthaus about whether global warming may be producing more extreme cold weather in the mid-latitudes, just like what much of America experienced this week.

To catch future shows right when they are released, subscribe to Inquiring Minds via iTunes or RSS. You can also follow the show on Twitter at @inquiringshow and like us on Facebook. Inquiring Minds was also recently singled out as one of the “Best of 2013” shows on iTunes — you can learn more here.

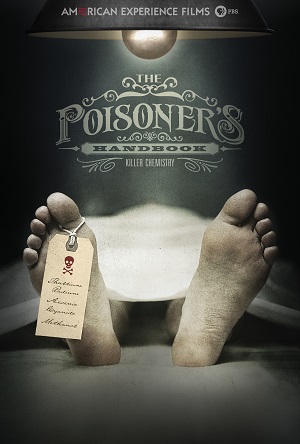

As a writer, Deborah Blum says she has a “love of evil chemistry.” It seems that audiences do too: Her latest book, The Poisoner’s Handbook: Murder and the Birth of Forensic Medicine in Jazz Age New York, was not only a bestseller, but was just turned into a film by PBS (you can watch it for free here).

The book tells the story of Charles Norris, New York City’s first medical examiner, and Alexander Gettler, his toxicologist and forensic chemist. They were a scientific and medical duo who brought real evidence and reliable forensic techniques to the pressing task of apprehending poisoners, who were running rampant at the time because there was no science capable of catching them. “When Norris came to office in 1918, the same year, the city of New York actually published a report saying that poisoners could operate with impunity in New York City,” explains Blum on the latest episode of the Inquiring Minds podcast [stream below].

[protected-iframe id=”bf14820f6923da0ca58492c58e1995a7-5104299-30178935″ info=”https://w.soundcloud.com/player/?url=https%3A//api.soundcloud.com/tracks/128763855&color=ff6600″ width=”100%” height=”166″ scrolling=”no”]

Arsenic, cyanide, chloroform — such were some of the favorites of poisoners in the 1920s. Detecting each one presented a different scientific challenge. Take arsenic: “It’s tasteless, so you can put it into anything and your victim doesn’t know,” says Blum. “It’s odorless. They can’t find it that way either. It mimics the symptoms of a natural illness … and, you can’t find it in the body. So even if you’re suspicious, you can’t prove that that person was poisoned. So no wonder it was a golden age for poisoners.”

Deborah Blum.

Forensic chemistry has come a long way since then, and poisoners don’t exactly run rampant any longer. But poisoning still happens. And as Blum notes in the other branch of her writing — reporting on environmental chemistry for The New York Times — environmental contaminants are, in effect, poisons as well.

So on the podcast, Blum helped us to compile this list of the six most worrisome modern day poisons, whether environmental or otherwise, chosen both for their prominence and for the danger they pose. Here they are, progressing from the environmental to the, er, homicidal:

1. Lead. Mother Jones’ Kevin Drum has documented just how deleterious this naturally occurring heavy metal is to us. Lead is particularly dangerous to children, because it acts as a neurotoxin that can stunt brain development. And it’s all around us: Naturally occurring in the soil, but also in substances ranging from paint in older houses, to pipes, to lipstick (the latter in very small amounts that the FDA says are safe).

“As a poison, there’s not one redeeming thing you can say about lead. It’s just bad,” says Blum. “And I like to remind people, it’s still around, we’re still exposing ourselves to it, and everyone’s at risk.” For more comprehensive information about lead risks in your home, see this infographic or click here.

Aram DulyanNative arsenic from the Natural History Museum, London.

2. Arsenic. Another naturally occurring heavy metal, arsenic may not be the favored tool of criminal poisoners that it once was. But its environmental presence remains a serious hazard, in both food and water. “Arsenic is also unambiguously bad for you,” says Blum. “It’s bad at a high dose, and it’s bad at a very low dose.”

Because arsenic is naturally found in the Earth’s crust, it makes its way into groundwater, and some of us drink it in dangerous concentrations. One risk arises when people dig their own private wells. Arsenic is also a byproduct of industrial activities like mining and smelting, and it makes its way into our food: Rice products are a particular concern. Long-term exposure can lead to various types of cancer, among other health threats.

Judy van der VeldenCarbon monoxide detector.

3. Carbon monoxide. “I do Google alerts on poison and poisoning, and there are some days where my dose of 10 news stories about people made sick or dead are all carbon monoxide,” says Blum. “Especially in the winter. Especially after a big storm, or in cold temperatures.”

Carbon monoxide is a gas that has no color or odor, but that can kill quickly if it is allowed to reach high concentrations in an enclosed space. It results from combustion in gas appliances, chimneys, heaters, generators, and cars. According to the CDC, 400 Americans die each year from carbon monoxide poisoning.

Notably, none of these hazards — lead, arsenic, carbon monoxide — represent some fancy new chemical innovation. Rather, they’re enduring poisons, to which we continue to live in close proximity. “They’re a reminder that we are smarter than we were, about poisonous things, in the days of Gettler and Norris,” says Blum. “But we’re not as smart as we should be.”

And then there are the substances that malicious poisoners tend to turn to today. Intentional poisonings are not nearly so rampant as they were in the 1920s, but they’re still out there. Here are some of today’s poisoners’ favorite tools:

4. Ethylene glycol (antifreeze). Ethylene glycol is the top ingredient in antifreeze, among other chemical substances. And “it’s actually one of the No. 1 homicidal poisons in the United States,” says Blum. The reason is that ethylene glycol has a sweet taste, a perfect quality in the hands of a poisoner. Plus, buying antifreeze is not generally seen as a suspicious activity.

PBS

Here’s one ethylene glycol case: A Georgia woman named Lynn Turner was convicted in 2004 of murdering her husband, and later her boyfriend, by serving them antifreeze, apparently in Jello and other foods and drinks. Here’s another: A doctor in Houston was indicted last year for allegedly placing ethylene glycol in a colleague’s coffee and claiming it was an artificial sweetener, Splenda. (The case is awaiting trial.)

“You see people turn to it a lot,” says Blum. “It’s a very nasty poison. It metabolizes to form these very sharp crystals, calcium oxalate crystals, that will slice and dice your kidneys.” Also at risk are animals, says, Blum: Ethylene glycol is “the No. 1 choice” when angry neighbors decide to poison a pet.

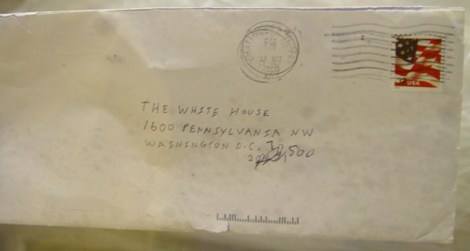

5. Ricin. In April of last year, an envelope was received at the U.S. Capitol containing a “white granular substance.” The letter had been sent to the office of Mississippi Sen. Roger Wicker (R). Upon analysis, the substance turned out to be ricin, an extremely deadly, naturally occurring poison that is found in castor beans and can be created from byproducts of the making of castor oil.

Ricin can come in various forms, including powder or mist, and when inhaled or ingested, causes cell death. This wasn’t the first time there was an attempt to send it through the mail: In 2003, two ricin letters were found at postal facilities in South Carolina and Tennessee; one was addressed to “The White House.” Ricin has long been a favored bioterror agent; for a thorough review of its history and biological effects, see here.

FBIAn FBI-released image of a ricin letter addressed to the White House in 2003.

6. Polonium-210. Finally, we come to the really high-tech poisoning. The radioactive isotope Polonium-210 decays and releases alpha particles; if it does so inside your body, it can be lethal even in small amounts, bringing on death by radiation poisoning.

Polonium-210 has been in the news because of charges (unproven ones, Blum thinks) that it was used to murder Yassir Arafat; before that, a Russian dissident, Alexander Litvinenko, was confirmed to have been killed with Polonium-210 in 2006. But unlike antifreeze, this one is hard to get your hands on: You need a nuclear reactor to make it in deadly amounts, though it also occurs naturally in the Earth’s crust and thus, is present in small quantities in the environment.

Poisoners who actually try to wield substances like these are undoubtedly “creepy, cold, and calculating,” as Blum puts it. But the real takeaway lesson from her writings and research on poisoning, she thinks, is a different one.

“Most of us are surrounded by these really bad things, and we don’t try to harm people with them,” Blum says. “Most of us really want, I think, to see our chemical world be one that makes people safer. And so it’s a really interesting way to explore our history and who we are.”

This story was produced as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

This story was produced as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.