Four years ago, California passed a groundbreaking environmental justice bill that requires the state’s local governments to address pollution, contamination, and other hazards in disadvantaged communities by integrating environmental justice principles into their municipal planning processes and thoroughly engaging communities before updating their general plans. The goal was to reduce pollution exposure and improve air quality for the communities that need it the most.

But implementation of the new law, known as Senate Bill 1000 (SB 1000), has been tricky. To try to ensure that local governments comply, California Attorney General Xavier Becerra’s bureau of environmental justice has sent letters to nearly a dozen municipalities offering feedback, pointing out shortcomings, and giving guidance on how to better comply with the law. In a June letter to rural Tulare County, for example, the bureau urged the county not to rush through its general plan update before fully engaging with disadvantaged communities, and to account for the obstacles that the COVID-19 pandemic poses for community engagement.

Those were the same concerns that environmental justice advocates have raised in the city of Santa Ana for months as they’ve watched city planners move forward with the city’s update of its general plan, which officials are trying to finalize by the end of the year. The COVID-19 pandemic has devastated Latino communities in Orange County, and particularly in Santa Ana, a densely populated city of about 337,700 residents that is 77 percent Latino. Like other vulnerable communities across the state, Santa Ana residents have been disproportionately burdened by pollution, poverty, and health disparities for decades. SB 1000 promises to finally alleviate those burdens — but if city officials rush through the planning process during a global health crisis, that promise might be broken.

Last week, the attorney general’s office weighed in on Santa Ana’s planning process. The environmental justice bureau said that it considers the city’s timeline unrealistic and not in line with the law’s requirements that overburdened communities be engaged during every stage of a general plan update. The bureau also criticized Santa Ana’s failure to address lead soil contamination and other environmental justice concerns as part of the update, a shortcoming that community advocates and residents described as particularly dangerous for children’s health during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“[Lead poisoning] is a public health crisis because children are being confined to areas that are contaminated, that have toxic lead levels, and they don’t have the ability to move about as they did before,” said Enrique Valencia, project director of Orange County Environmental Justice (OCEJ), a public advocacy organization in Santa Ana. “We need to look at this issue holistically — and as a city, we need to figure out how we’re going to address it.”

In its letter, the bureau notes that although Santa Ana began its general plan update in 2016, its engagement process with disadvantaged communities began only three months prior to the release of the draft general plan update this August.

“One of the basic purposes of SB 1000 is to provide environmental justice communities with a meaningful opportunity to engage in government decisions that affect them. The City’s accelerated timeline does not appear to allow for this meaningful community engagement process to occur,” Deputy Attorney General Rica Garcia wrote in the letter.

General plans outline the goals and policies that city and county governments will implement as part of their land use, planning, and development. In Santa Ana, the general plan hasn’t received a comprehensive update since 1982, and the current plan aims to establish a vision to guide the city’s growth over the next 20 years.

Melanie McCann, a senior planner in Santa Ana’s planning division, told Grist that the city is reviewing the content of the letter and will be reaching out to the attorney general’s office to get clarification on the comments.

“At this point, city staff is assessing how the suggestions from the attorney general might impact the adoption schedule, but it’s too soon to tell,” said McCann.

OCEJ and other environmental advocates in Santa Ana are calling on the city to put the brakes on its general plan update so that the communities, including low-income residents who often have limited access to high-speed internet and the technology needed to participate in virtual public meetings, can take part in the process. In a letter to city officials last month, Valencia suggested that the city postpone the community review process until 2021 to give residents the opportunity to provide “critical input.”

“It’s really a tragedy — the tragedy of what’s happening to Senate Bill 1000 as it’s being implemented by the city,” said Valencia. “The current city administration, they’re trying to fast-track the adoption of this plan in a situation where we’re in a pandemic.”

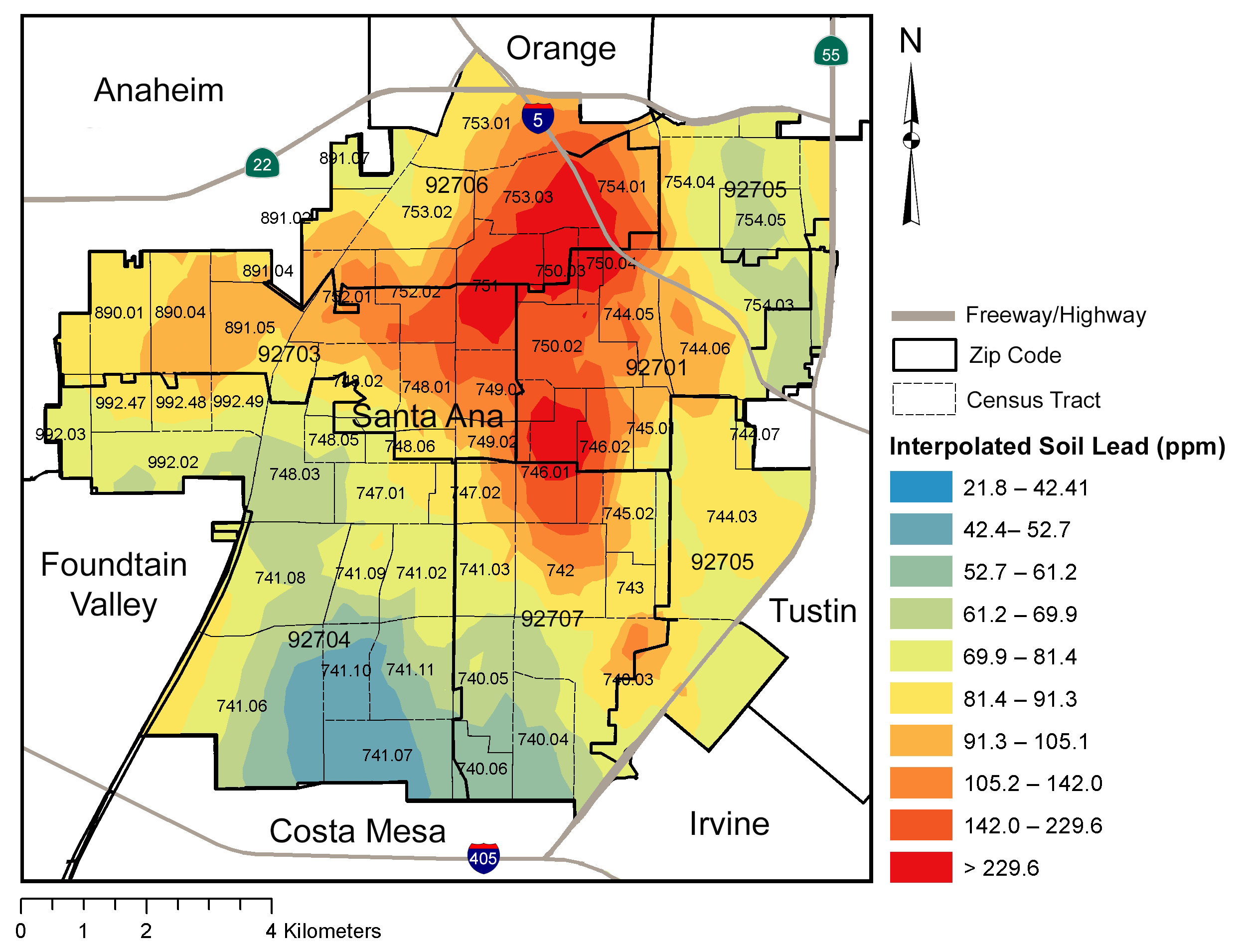

OCEJ is part of a coalition of residents, advocates, and academic scholars that has spent three years raising community awareness about the dangers of lead exposure in Santa Ana. This summer, the coalition released a study highlighting how children in Santa Ana’s poorest areas are at a higher risk of being exposed to lead soil contamination. The study, led by a team of researchers at the University of California, Irvine, analyzed more than 1,500 soil samples collected throughout the city. It found a higher incidence of lead contamination in the city’s poorest neighborhoods and areas with the highest percentages of young children, residents without health insurance, and renters.

When the researchers analyzed maximum lead concentrations, they found that 56 different census tracts, where more than 28,000 children reside, had maximum lead concentrations that exceeded the level that the California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment considers dangerous for children: 80 parts per million in residential soil. And 20 census tracts, where more than 12,000 children reside, had maximum lead concentrations higher than 400 parts per million, the federal standard set in 2000 by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) as hazardous for children in residential play areas. (In 2012, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention declared that no level of lead is safe for children, and lead soil experts recommend more health protective soil standards of 40 parts per million.)

Soil lead (Pb) concentrations based on 1528 samples collected in Santa Ana, CA. Map by Shahir Masri, Program in Public Health, University of California, Irvine. Published in Science of the Total Environment

Shahir Masri, one of the study’s lead co-authors, told Grist that the Santa Ana study shows that communities burdened by lead contamination are being left behind — particularly those without the financial means to address lead contamination in their soil themselves.

“We have communities that are exceeding what EPA has decided is too high a risk, too high a concentration in the soil, and those communities aren’t being served,” said Masri, an assistant specialist in air pollution exposure assessment and epidemiology at the University of California, Irvine.

He said that the study also highlights the importance of supporting communities that take the initiative to gather data in order to understand the hazards in their neighborhoods.

“If we don’t have reports of high pollution levels in our own environment, it’s possibly because investigations haven’t been launched yet,” Masri said.

The study followed up on findings from a 2017 investigation (conducted by this reporter for ThinkProgress), which found lead levels surpassing what one state agency considers dangerous for children in nearly a quarter of more than 1,000 soil tests conducted in predominantly immigrant and low-income neighborhoods in Santa Ana. Public health data also showed that the number of Santa Ana children who tested with dangerous levels of lead in their blood exceeded the state average by 64 percent.

For years, the state’s childhood blood lead level data has shown that Santa Ana has a greater number of lead-poisoned children than other Orange County cities, but the Orange County Health Care Agency (OCHCA) couldn’t explain why and had not mapped where hot spots of contamination exist so parents can avoid them. County data showed that, out of 16 environmental investigations OCHCA conducted from 2013 to 2015, only three were done in Santa Ana. Instead, the agency relied on public awareness campaigns and outreach that didn’t emphasize soil exposure, even though the state department of public health says dust and soil contaminated by leaded gasoline is the most significant environmental lead contaminant in California and the dominant source of lead exposure for the state’s children, due to decades of leaded gasoline use.

One of the key concerns relayed by the attorney general’s office is that the general plan update lacks tailored environmental justice policies to reduce health risks unique to Santa Ana. For example, the letter states that although Santa Ana is aware that disadvantaged communities are significantly burdened by lead contamination, the draft general plan has only two implementation actions aimed at addressing the problem. These don’t include timelines to implement programs, details specifying how the city will identify key community stakeholders as collaborators, or implementation benchmarks. The attorney general’s office recommends that the city not only strengthen existing measures, but also add more specific measures focused on addressing lead contamination. The letter cites the northern California city of Richmond’s policies as a model that Santa Ana could follow to ensure that contaminated sites are remediated prior to allowing new development, for example.

The attorney general’s office also recommended that Santa Ana collaborate with overburdened communities in order to solicit ideas for how to address lead pollution burdens. Community advocates say that the city has so far failed to take them up on an invitation to collaborate despite attempts by OCEJ and others to partner with the city on a plan to address pollution.

“There is a precedent in Santa Ana — that’s a very unfortunate precedent — of not wanting to work on this issue because it’s almost like it’s out of sight, out of mind,” said Valencia.

He and his co-author, University of California, Irvine, Assistant Professor Alana M.W. LeBrón, have spoken publicly at city council meetings and reached out in writing to invite the city to partner with the coalition to tackle lead contamination. So far, the city has not taken any concrete steps to do so, despite the availability of specific, localized data showing lead contamination throughout the city.

“What we really want to see is commitment to actually reduce the exposures,” said Valencia, noting that the invitation to collaborate is open-ended. “Why not use this data to better develop environmental justice goals and metrics?”

Other community advocates and residents have experienced similar frustrations. Santa Ana resident Jose Rea, who is treasurer of the Madison Park Neighborhood Association, said the nonprofit has likewise reached out to the city throughout the general plan update process, hoping to ensure that the concerns raised by residents throughout the 17 neighborhoods the state classifies as disadvantaged are heard. The association, which represents 10,000 residents in southeast Santa Ana, has met with city officials and raised concerns about the levels of air pollution in their neighborhoods. Dismayed by the lack of official action, however, the group ultimately decided in 2017 to find a way to collect air quality data themselves. With a grant from the California Air Resources Board, the association is launching a pilot air monitoring system and plans to hire an air pollution specialist to analyze the data.

A boy stands with his bike in the Santa Ana, CA, neighborhood where the author found soil lead levels as high as 4,094 ppm, which is more than 50 times higher than the hazard level set by the state. Photo by Daniel A. Anderson

In a series of letters sent to city planners, the neighborhood association urged the city to incorporate environmental justice concerns more robustly into the general plan update, to engage more fully with residents, and to adopt a new timeline that takes into consideration the limitations of public involvement due to the pandemic.

“Our argument is: Look, if you have [17] neighborhoods that are considered disadvantaged communities, what outreach have you done in these communities to make sure their concerns are heard?” said Rea.

These are neighborhoods whose needs have historically been the “least acknowledged, and seldomly addressed by government decision-makers,” according to a letter to the city sent by the neighborhood association and the environmental law clinic at the University of California, Irvine. Indeed, one report commissioned by Santa Ana 40 years ago as the city was last preparing to update its general plan indicates that city officials were aware of multiple neighborhoods on the east side that lacked buffering between industrial and residential areas — problems described at the time as “industrial/residential incompatibility.” Some of these neighborhoods are in locations where the 2017 ThinkProgress investigation found high levels of lead contamination. For example, zip code 92701, which encompasses the neighborhoods east of downtown Santa Ana, had the highest percentage of elevated soil lead levels, with 35 percent of tests showing levels at or higher than 80 parts per million. It also had the highest percentage of children under the age of 6 with blood lead levels at or above the actionable level set by the CDC.

Four decades later, the draft general plan update includes policies to develop buffers in areas used for industrial purposes, something that the attorney general’s office described in the comment letter as a positive step. But the letter also criticized the policies, because they don’t designate the appropriate distance or standard for buffer zones.

“We recommend the City define these requirements more clearly and consider establishing affirmative requirements for separation between industrial uses and sensitive receptors in the City’s disadvantaged communities,” the letter states.

Engaging impacted residents and adopting a community-wide approach to eliminating lead poisoning aligns with what lead contamination experts recommended as best practices in a recently published article in the Yale Journal of Health Policy, Law and Ethics. Health and housing justice expert Emily Benfer told Grist that evidence of lead contamination in Santa Ana highlights the importance of recruiting leaders among the affected populations, especially low-income and traditionally-marginalized communities, and informing residents of the health hazards they face, discussing how they can protect their family, and asking what solutions will work in their lives.

“The evidence underscores what we’ve known: that lead is a pathway by which racial inequality literally gets into the bloodstream, and that lead exposure of this magnitude cannot be resolved by reactive and siloed interventions,” said Benfer, a visiting professor at Wake Forest University School of Law.

Given the irrefutable evidence of lead contamination, Benfer said it’s urgent that Santa Ana officials act quickly and focus on primary prevention solutions, which means finding the environmental source before a child is ever exposed to lead. The scientific consensus is that no lead level is safe for children, given the neurotoxin’s irreversible effects on the developing brain. Researchers have found elevated blood lead levels can lead to increased aggression, lack of impulse control, hyperactivity, inability to focus, inattention, and delinquent behaviors. A growing body of research also shows that even children who have blood lead levels below 5 micrograms per deciliter can experience serious consequences such as cognitive deficits, behavioral issues, and educational delays. The cascade of harms for children who are exposed to lead makes immediate action imperative, according to Benfer.

“A delay — even in the form of delaying bringing people together to devise a response — is incredibly harmful and will have a consequence on how those children fare in the future,” she said. Benfer also noted that collaboration between researchers and community members is one of the most effective ways to devise policy that’s data-driven. This approach aligns with a growing body of evidence demonstrating that intervention at the community level is more effective than solely targeting homes child-by-child. “Focusing on the community at risk can not only reduce lead poisoning rates, but it also supports broader movements to address structural racism and housing and environmental injustice in those communities too,” said Benfer.

Nearly 25 percent of soil tests conducted by the author in Santa Ana, CA, in 2017 found lead levels that exceed what a state agency considers safe for children. Photo by Daniel A. Anderson

Santa Ana parent Rubi Barreto supports a community-wide approach, something that she believes could benefit residents in the neighborhood where she grew up and still lives today: the historic Delhi barrio, where Mexican and Mexican American residents were segregated in the first half of the last century. Today, according to state data, the census tract that encompasses the Delhi barrio is the most disadvantaged of the city’s 17 communities classified as such, and its pollution burden ranks worse than 97 percent of the rest of the state. The tract, which is predominantly Latino, ranks in the top percentiles for toxic releases, cleanups, groundwater threats, traffic pollution, and hazardous waste. The barrio itself abuts an industrial corridor that has long concerned Barreto.

Barreto, 29, was among the residents who participated in the recent soil study by allowing researchers to test the soil in the yard of her parent’s home, where today she lives with her boyfriend and their 2-and-a-half-year-old daughter, Jade Rosales. Two of their soil samples tested higher than 120 parts per million, while one sample in the front yard tested below 60 ppm. Barreto believes the front yard’s lead level was lower because her father, a gardener, replaced that dirt with top soil so his plants could thrive. The results of the study worry her because they show that the contamination is widespread and dispersed throughout the city.

“It actually is more alarming to me because I thought it was just my house that I had to protect my baby from. But knowing that it’s everywhere — that really concerns me, because I don’t know what actions to take,” said Barreto, an Orange Coast community College student studying to be an ultrasound technician.

Now, Barreto said she’s unsure whether it’s safe to take her daughter to parks or local playgrounds. The community, she added, needs to be properly informed by the city about how children can be protected, steps residents can take to remediate the soil in their yards, and ways the city can address soil contamination in public spaces. The top priority should be the health of Santa Ana’s children, said Barreto, and addressing an environmental justice issue “that’s going to affect Santa Ana’s future.”