Before it exploded last June, Philadelphia Energy Solutions (PES) — the largest crude oil refinery on the East Coast — was processing 335,000 barrels of oil each day. It was also producing some of the highest levels of benzene pollution of any refinery in the country, according to a new report by nonprofit watchdog group the Environmental Integrity Project.

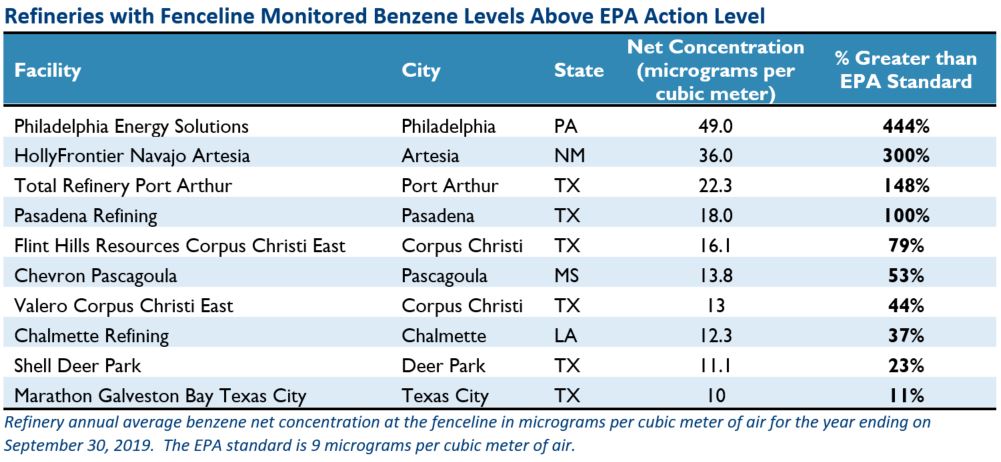

The report, which follows a recent investigation of PES’s benzene pollution by NBC News, found that 10 refineries across the U.S. were releasing cancer-causing benzene into nearby communities at concentrations above the federal maximum in the year ending in September 2019. Under 2015 EPA rules, facilities are required to investigate where their toxic emissions are coming from, then take immediate action to reduce impacts — both of which PES failed to do. The refinery had an annual average net benzene concentration that was more than five times the EPA standard, beating a long line of refineries in the oil-friendly state of Texas. Out of the 114 refineries that the group examined across the country over the course of a year, PES emitted the highest levels of benzene.

Environmental Integrity Project

That includes the period after the refinery was shut down following the explosion.

Residents of South Philadelphia say they were awakened in the early hours of June 21, 2019 by a loud boom. Large pieces of debris poured down on the streets followed shortly by the smell of gas. Neighbors looked out their windows and saw clouds of dark smoke billowing from the nearby complex, which already had a history of safety issues.

For a while, that seemed to be the end for the refinery. Rather than make repairs and clean up the mess after the June incident, PES shut down the facility and filed for bankruptcy. The company put the 1,300-acre waterfront property up for sale, either to be maintained as a refinery or to be turned into housing or mixed-use development. And last month, after a closed-door auction in New York City, Hilco Redevelopment Partners, a Chicago-based real estate company, was the selected winner. But just when it seemed the PES refinery complex would shut down for good, the Trump administration got involved, offering its help last week to spurned bidders who are challenging Hilco’s victory because they want to keep the property processing crude oil.

The idea of keeping the refinery active doesn’t sit well with some environmental activists, especially in light of the new benzene report.

“Today’s report is just one more factor and data point on why this plot of land should not be put back into a use that puts local communities at risk,” said David Masur, executive director of PennEnvironment, a statewide environmental group working for clean air and water.. “Whether it’s an explosion or a constant threat of pollution from known carcinogens, the choice of putting a refinery there is just too dirty and dangerous.”

A community fuming

South Philadelphia has long been a diverse cultural hub for the city. It also faces multiple sources of pollution. In addition to the PES refinery complex, the largest source of particulate air pollution in Philadelphia and a repeat violator of the Clean Air and Water Acts, South Philly also has major arterial highways, the Philadelphia International Airport, large industrial factories, and other processing facilities.

More than 5,100 people live in the area within a one-mile radius of the PES refinery. Most of the residents are black, and 70 percent of the residents live below the poverty line. These residents also suffer from disproportionately high rates of asthma and cancer.

In a letter sent to the City of Philadelphia Refinery Advisory Group — a group the city created in wake of the June 21 explosion — at the end of October 2019, Drexel University researchers summarized the health impacts of living near the PES refinery based on data they’d gathered. They listed negative birth outcomes, cancer, liver malfunction, asthma, and other respiratory illnesses. They also included mental health impacts such as stress, anxiety, and depression that come with living near a large industrial site like PES.

“Because the PES refinery is immediately surrounded by several neighborhoods, communities near the refinery will be disproportionately affected by compounds released by it,” Kathleen Escoto, a graduate student at the Dornsife School of Public Health at Drexel who was one of the authors of the letter, told Grist. “If the refinery released the highest levels of benzene in the country, especially considering its proximity to densely-populated areas, then the burden of disease that the refinery has on the surrounding communities is even worse than we thought.”

Benzene, a colorless chemical with a somewhat sweet odor that evaporates from oil and gas, is used as an ingredient in plastics and pesticides. According to the U.S. Center for Disease Control, exposure to benzene can cause vomiting, headaches, anemia, cancer, and in high doses, death.

Philly Thrive, a grassroots environmental justice group that has been raising awareness about the public health costs of living near a fossil fuel facility since 2015, has been organizing community members from South Philadelphia to fight against PES and to ensure that they have a seat at the decision-making table.

“Part of what Philly Thrive has faced when residents tell their stories about the impact of the refinery on residents’ health is confrontation from politicians and leaders, who challenge our personal stories, lived experiences, and wisdom,” said Philly Thrive organizer Alexa Ross. “It’s always been offensive, perplexing and confusing to be challenged on the basis of facts.”

The refinery’s fate

Despite the Trump administration’s efforts to keep the refinery in operation, the fate of the land is still up in the air. On Thursday, Philly Thrive organized a call bank session for members to make phone calls to Philadelphia Mayor Jim Kenney and the Industrial Realty Group, an alternative bidder on the property that wants to keep it as a refinery. They cited the new report as part of their reasoning that the refinery should remain closed.

“This report just leaves us fuming, speechless, dumbfounded, and reeling about how residents have known for so long that the refinery has been killing generations of Philadelphians, but politicians still ask us to prove it,” Ross said.

“Imagine if we actually have the right kind of air monitoring system we need,” she added. “Imagine what else would come to light about what facilities like the refinery has been doing to human health.”

A hearing to finalize the details of PES’s 11 bankruptcy sale is now scheduled for February 12 in Wilmington, Delaware.