The lines of voters stretch as far as the eye can see, winding their way to polling booths across the country despite a life-threatening pandemic, an economic crisis, and a year that’s been filled with upheaval and uncertainty as the United States heads into an exceptionally heated presidential election. That Americans from Georgia to Nevada to Wisconsin are donning their masks to stand for what they believe in, despite the risks to their health, is telling — and a clear sign of just how crucial this election feels for so many. This is particularly so for Americans who live in some of the country’s most marginalized neighborhoods. They understand that there is much more at stake than who will sit in the Oval Office. They are voting because their lives depend on it.

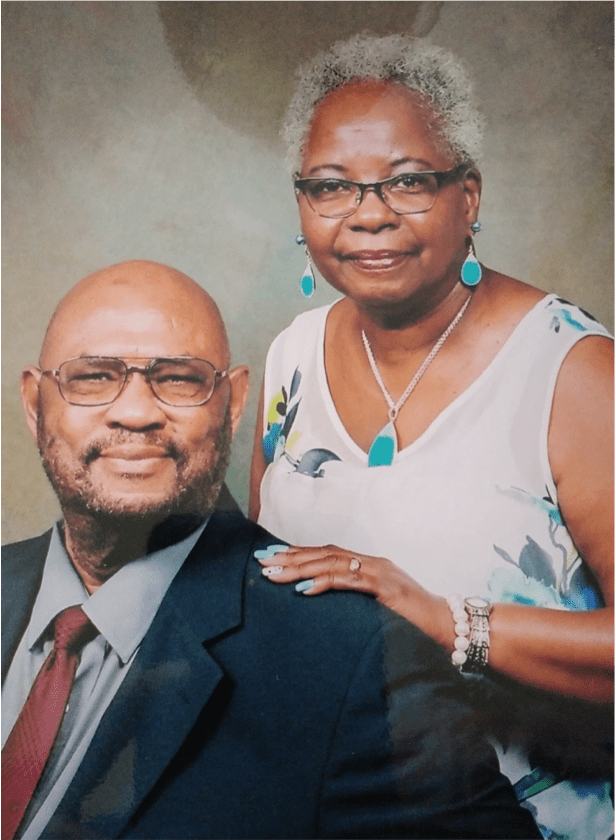

No one understands this better than Omega Wilson. For 26 years, he and his wife Brenda have fought to deliver basic public services such as sewer lines, city water lines, and paved streets to neglected, historically African American communities settled by formerly enslaved people in North Carolina’s Alamance and Orange counties. The Wilsons began waging this battle in the mid-1990s after they co-founded the West End Revitalization Association (WERA), a community development corporation, after discovering that the state was attempting to build a four-lane highway through the predominantly African American West End community — and doing so without publicly meeting with residents. Part of the West End is just outside the city limits of Mebane, but it is nevertheless under the city’s jurisdiction on matters like zoning and land use. Because of this, some West End residents don’t have a say on basic public service issues, despite living a quarter mile from the city’s sewer treatment plant. The community pushback on the proposed highway and the lack of basic services led WERA to file a civil rights complaint with the U.S. Department of Justice in 1999. Their concern was not just that the city had ignored their community’s voice on this one issue. It was the continuation of a deeply entrenched pattern of denying blacks and other people of color in these neighborhoods a voice by segregating, disenfranchising, and denying them the rights afforded to whites.

To this day, WERA continues this work by tackling environmental justice issues tied to waste management and the contamination of their environment. WERA was “supposed to dissolve in the dust and the pain and the struggle” within a few years, Omega Wilson said, but instead the organization has persevered, knowing that access to clean water, air, and soil are essential for all residents. Watching Americans march in the name of George Floyd this summer, Wilson understood that the protests went beyond calling for police reform. Floyd represents just one of many who have died at the hands of an indifferent system that suffocates Black Americans — whether it’s at the hands of police or at the fenceline of a polluting oil refinery. “There have been so many other people who died since and before,” Wilson said.

The urgency of this struggle is part of the reason why Wilson, after his mail-in ballot form failed to arrive at his home in a timely manner, decided to hand deliver his completed form to the ballot box at the Alamance County Board of Elections. In a letter to the editor published last month in the Mebane Enterprise, Wilson encouraged others to do the same. He wants to ensure that everyone’s vote is counted — and to avoid ongoing ballot rejection issues and confusion surrounding the mail-in voting process throughout North Carolina. This election, he said, is about sending candidates the message that it’s time for change. Wilson argues that an “Old South” attitude has persisted among a white governing establishment in both parties, which calls the shots and expects everybody else to get in line.

“When you talk to [candidates] personally, they want your vote, but they don’t get your message. So you have to say it over and over and over,” said Wilson, who is African American with Native American and white ancestry. Delivering that message through his vote is one way to overcome a history of voter suppression in the Black community, whether it’s through violence, poll taxes, voter intimidation, or the creation of voter ID laws.

Omega and Brenda Wilson in 2018. Photo courtesy Omega Wilson

After George Floyd was killed at the hands of police in Minneapolis, many asked: How do we achieve lasting change? There were renewed calls to finally address systemic racism. Yet even before that battle began, just months after millions of people took to the streets to stand up for that very change, Americans’ interest began dwindling. A Pew Research Center survey released in September found that support for Black Lives Matter is waning, particularly among whites. This doesn’t bode well. We know that placards on front lawns and protests in the streets will only take us so far. Denouncing racism is not the same as dismantling racism. What will it take to sustain this effort?

The late legal scholar and attorney Derrick Bell spent his career exposing how racism persists in our society, laws, and legal institutions. In his seminal law course casebook Race, Racism and American Law, which was first published in the early 1970s, Bell described voting as the most important function of the democratic process. However, writing in the wake of the historic 1965 Voting Rights Act, he wondered (prophetically, it turns out) whether the country’s historic pattern of waves of disenfranchisement following in the wake of expanded voting rights would soon repeat itself.

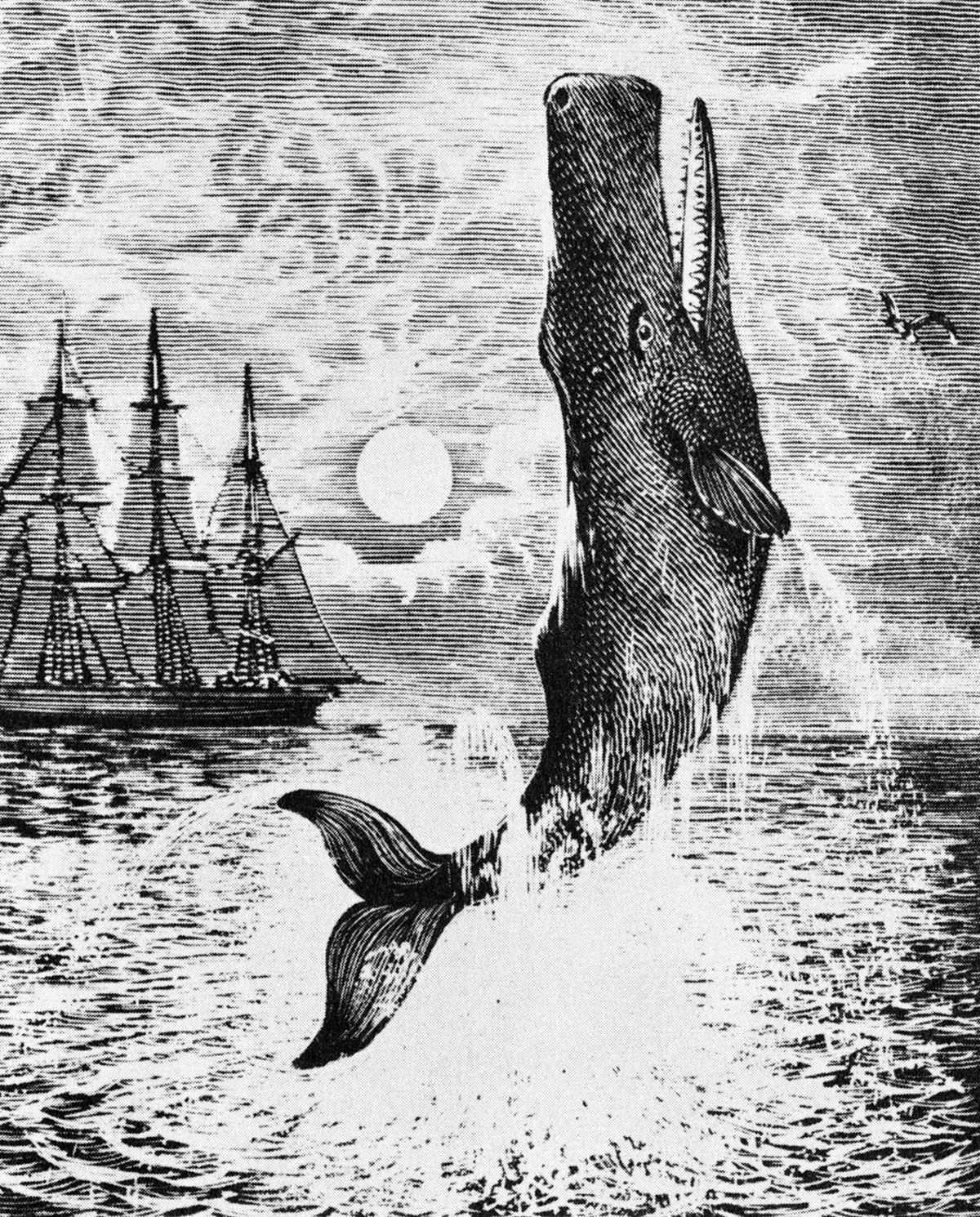

Could the United States uphold its democratic values? Case after case, Bell illustrates how the system, and its people, have failed to do this. Why, for example, did pre-Civil War judges uphold slavery in their legal decisions, even when they were morally opposed to slavery itself? Bell’s answer is that, although whites are willing to take a stand against racism, when it comes to implementing concrete measures to correct the wrongs of a discrimination, they do not act. He draws a comparison with the campaign to end the slaughter of whales. Eliminating racism, he notes, ranks only a step or two higher on the priority scale for most whites than the campaign to eliminate whaling. “In other words,” writes Bell, “racial equality, like whale conservation, should be advocated, but with the understanding that there are clear and rather narrow limits as to the degree of sacrifice or the amount of effort that most white Americans are willing to commit to either crusade.”

Bell isn’t the only American thinker to invoke whaling as a metaphor for the dangers of accepting the status quo. Many remember Herman Melville’s Moby Dick for the lessons imparted about the manipulative captain Ahab and the sailors who unwittingly followed him to the furthest reaches of the ocean, even as Ahab became consumed by his obsession to vanquish the titular sperm whale, no matter the cost. Melville’s tale, however, was also a warning about the dangers of pledging allegiance to destructive ideas set forth by the Captain Ahabs of our world — and of accepting ways of life and ways of living that destroy the earth and those around us. “How does one fare, having failed to be forewarned about our inner Ahabs or the risks of being led into complicity with madness, uncounseled on the wisdom of rejecting the obsessive quests that the world’s pulpits condone and its ports reward,” the ecologist Carl Safina wrote in a recent essay on the book. “Moby Dick is only partly about madness; it’s equally about banality.”

Today, as we take the steps necessary to protect the democratic ideals on which this country was founded — to ultimately bridge the divide between the privileged and those who don’t enjoy the freedom of a democratic way of life because of poverty, racial prejudice, and environmental injustice — is there common ground on which we can stand? Safina concludes that those are the lessons we must heed from Melville’s novel, which illustrated how life on the high seas brought men together in ways that could bridge the existing divides between people from vastly different circumstances.

“From a world he experienced as spherical from atop ships’ masts, Melville perceived a sea-level humanity, embracing and celebrating the latitudes and longitudes of human variation, now termed diversity,” wrote Safina.

But first, Americans must make the decision as to whether or not they will continue to follow Ahab. In Moby Dick, Melville foreshadows what’s to come through the terror of the whale line, the tool Ahab expected to use to catch his prey. A hempen rope attached to a harpoon, the whale line twists throughout the whale boat. It poses a threat to every oarsman, because in an instant it can yank that oarsman to his death during the commotion of a whale kill. “All men live enveloped in whale-lines. All are born with halters round their necks; but it is only when caught in the swift, sudden turn of death, that mortals realize the silent, subtle, everpresent perils of life,” writes Melville.

Culture Club / Getty Images

We saw how quickly these lines twisted taut on Saturday when even during the most American of acts — a peaceful march of protest — demonstrators in North Carolina were pepper-sprayed and arrested by law enforcement as participants made their way to an early voting site to encourage election turnout. Those participants wore sweatshirts bearing the mantra of the late civil rights icon and congressman John Lewis (“good trouble”), chanted “black lives matter,” and paused to honor George Floyd along their route. That these voters would take to the streets to remind residents to exercise their right to vote indicates that they know exactly what’s on the line — not just in today’s election, but in today’s America.

For the poor and people of color in America, the perils that Melville writes of are ever-present in daily life, whether they are marching down the street or sleeping at home. Death is no stranger to neighborhoods where people have trouble breathing due to toxic emissions from nearby factories, or for people who live under the constant suspicion of law enforcement simply for being brown or black. As Bell wrote in an article on America’s legacy of slavery, as elusive as racial justice might seem, by pinpointing where and how racism exists, we take a first step.

“We shouldn’t forget that the most pernicious form of racism is the racism within our very laws, our institutions and forms of government,” he wrote. Our constitution may pledge equal protection for all under the law, but it has not fulfilled its promise to Americans living under clouds of pollution, near toxic waterways, and on contaminated soil. Democracy is a two-way street that requires the people to hold their leaders accountable to that pledge. Should we fail, the lines will continue to be drawn taut, denying equality to these communities.

Will democracy be swallowed whole by Ahab’s obsession? President Donald Trump, in tones reminiscent of a carnival barker, recently promised his followers that they are “going to see a great red wave” on election day. But beneath the deck we see a very different reality: a campaign willing to suppress the most democratic of our rights. The endgame for Trump’s team is voter suppression. Republicans are focusing their energy on discrediting vote-by-mail and withholding the resources needed for the election to run smoothly. As Barton Gellman recently wrote in The Atlantic: “Trump does not want Black people to vote…. He does not want young people or poor people to vote. He believes, with reason, that he is less likely to win reelection if turnout is high at the polls.”

America, as we can see in the upswell in voters who have shown up to cast their votes, is responding to this threat to our democracy much like the sperm whale does when it responds to attacks: en masse. The lines of voters wending their way to the polling booth send a message as powerful as the whale lines in Moby Dick, which “silently serpentine about the oarsman” in “graceful repose … before being brought into actual play.” By showing up, voters are engaging despite the obstacles set in their way; they are grabbing hold of the reins of a democracy that for so long has not lived up to its promise and are using that power to save America from drowning. Bell saw how engagement and commitment are two of the crucial elements in addressing racism, and he recalled how Black Americans have long found meaning by tapping those traits — even when facing the “unbearable landscape” of slavery. They did so by “carving out a humanity for oneself with absolutely nothing to help — save imagination, will, and unbelievable strength and courage,” he wrote.

By going to the polls, Americans are taking a stand on which way the ship will be steered. Will America at last chart a new course toward justice? That will depend on whether Americans understand that it’s not just a matter of voting in this election: It’s making sure that vote counts far beyond November 3, because this is not just a vote to preserve democracy. It’s a vote to create the type of democracy that actually provides equal protection under the law for all. It’s a vote to protect our oceans, to change the way we live and do business, to create a system that lives up to the promise of every protester who has marched in the streets calling on America to ensure that black lives matter.

There is little time to waste. By the 1840s, when Melville was sailing in the Western Pacific, Safina notes that the whale population had been so decimated that it became more and more difficult to find them, leading the writer to ask in Moby Dick whether “Leviathan can long endure so wide a chase, and so remorseless a havoc.” The elusive white whale did in fact survive in Melville’s tale, and justice was served for the rightful victor. But the ultimate message in Moby Dick is understanding how we might create a different world — one in which we coexist peacefully, one in which we fight to protect our democracy by coming together and refusing to yield to the forces that might tear this country apart. The solution is right in front of us. “Round the World!” Ahab commanded his crew. “There is much in that sound to inspire proud feelings,” writes Melville. “But whereto does all that circumnavigation conduct? Only through numberless perils to the very point whence we started, where those that we left behind secure, were all the time before us.” Only we can save ourselves, and, as elusive as that goal of equality for all may seem, that is a dream worth chasing to the furthest reaches of the sea.