This post has been updated.

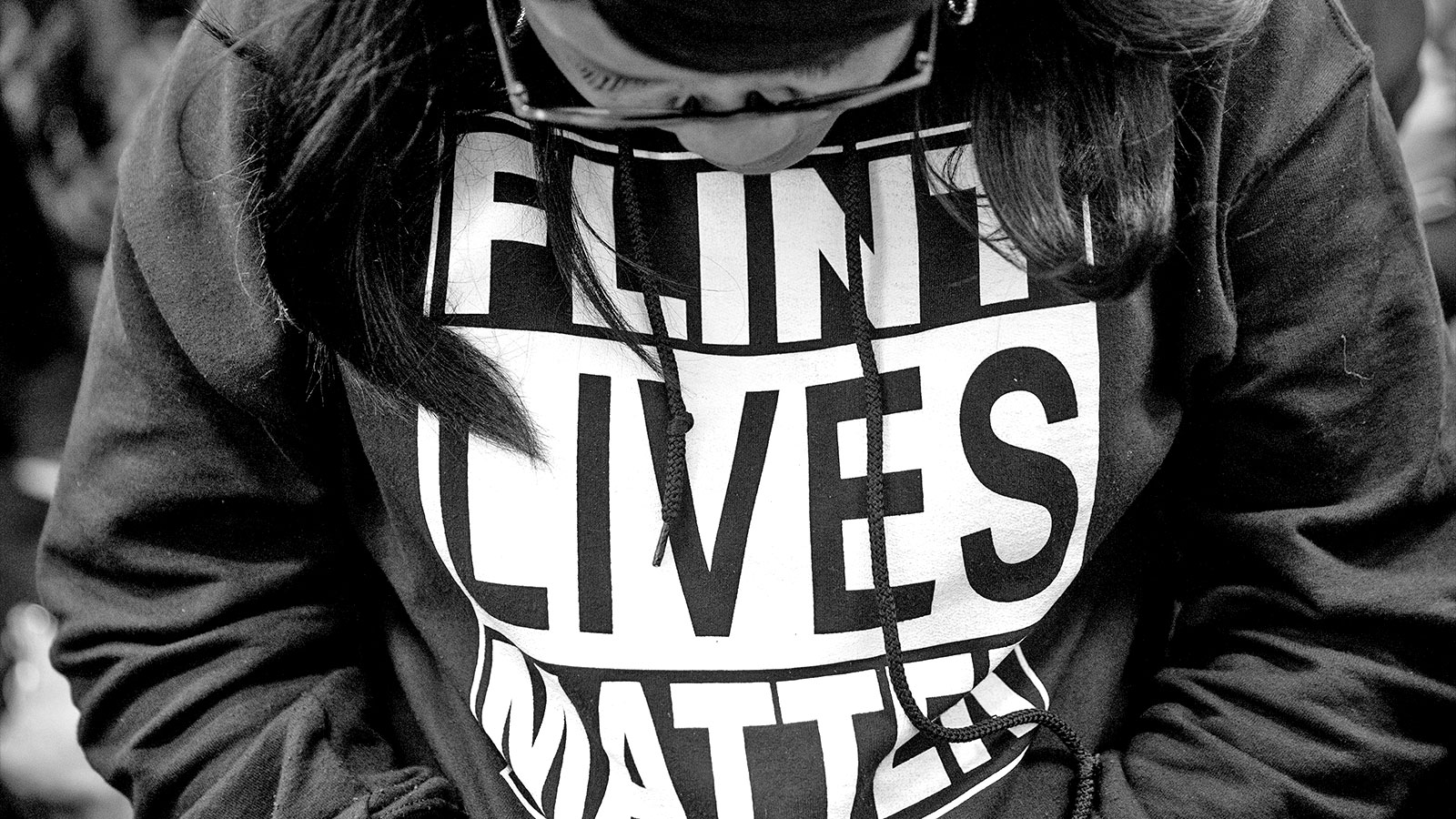

No punishment has yet fit the crime of the Flint water crisis, complete with its child poisoning and lethal outbreak of Legionnaire’s disease. After a prior investigation fell apart in 2019, Michigan state prosecutors unveiled a slew of fresh charges against nine figures involved in the fateful penny-pinching move to switch Flint’s water supply from Lake Huron to the Flint River in 2014. The river’s waters, polluted from decades of industrial waste, corroded Flint’s old water pipes, releasing lead into drinking water and into the brains of thousands of children.

Lead is a neurotoxin with irreversible effects and is not safe to ingest at any level. The New York Times and Education Week reported in 2019 that the percentage of Flint’s school children who qualified for individualized special education services more than doubled from 13 percent before the crisis to 28 percent after. Add to those victims, the one dozen people who did not survive their bouts with Legionnaire’s disease, a type of pneumonia that scientists linked to the water supply switch. The PBS program Frontline determined in 2019 that a total of 115 Flint residents had died of pneumonia during the outbreak, suggesting deaths attributed to Legionnaire’s had been undercounted, potentially by up to a factor of nearly 10.

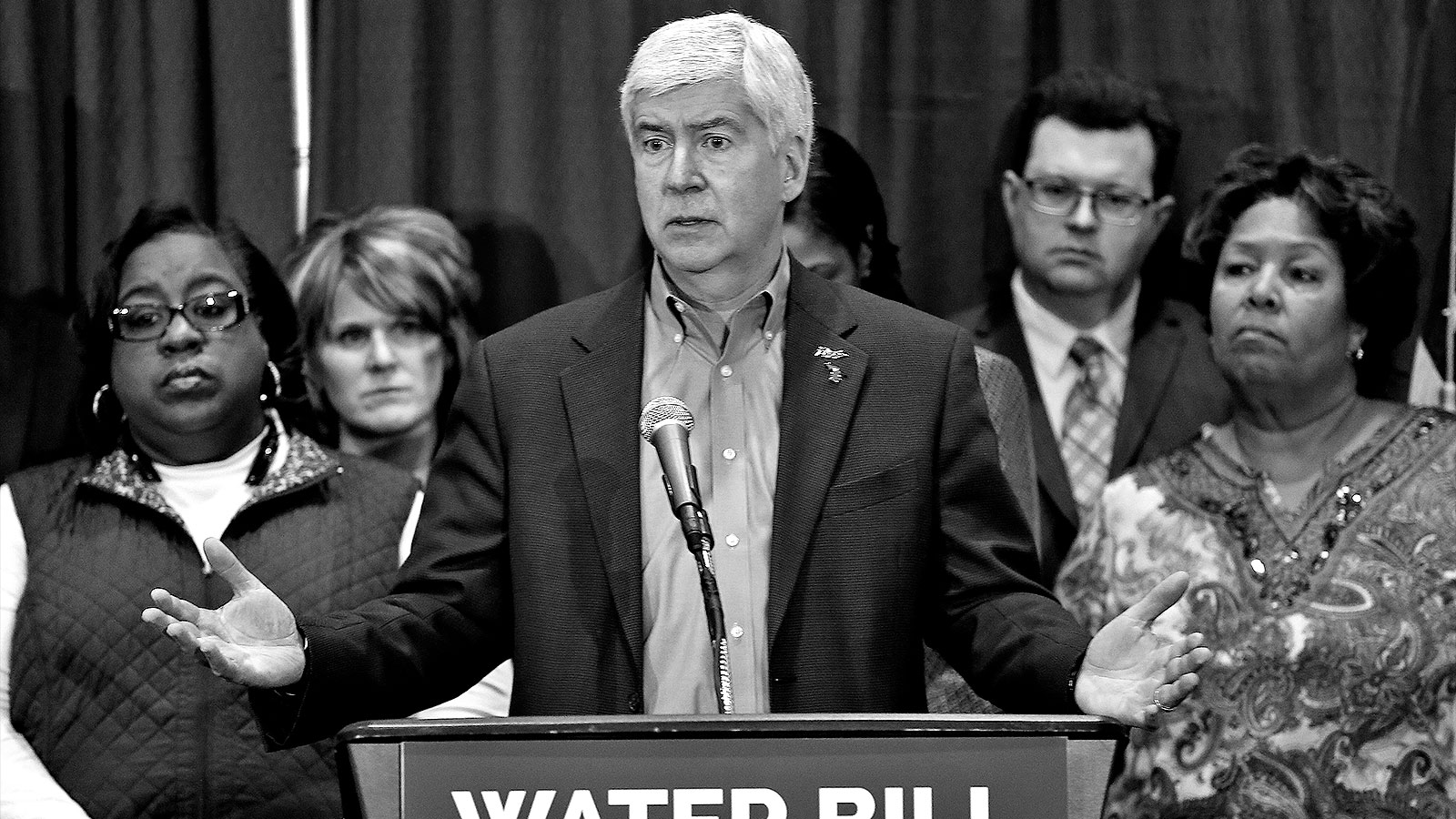

Seven of the nine defendants — which include former state health and communications officials, former state-appointed emergency managers, and an ex-Flint public works manager — are staring down 5 to 15 years in prison for crimes including involuntary manslaughter and perjury. Former Michigan Governor Rick Snyder, however, only faces two relatively minor counts of willfully neglecting to intervene in his underlings’ incompetence and failing to adequately protect the public against disaster.

In theory, Snyder could end up in prison for a year, and prosecutors say it is possible he could face more charges. Without them, he would be getting off easy for being asleep at the wheel during one of the greatest instances of environmental injustice in recent American memory.

Or was he truly “asleep”? Snyder’s excuse during the crisis and ever since is that he never knew enough to stop the falling dominoes of decisions and cover-ups happening underneath him. Yet plenty of circumstantial documentation begs the contrary.

The City of Flint switched its water supply to the Flint River in April 2014. Snyder testified to the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform in March of 2016, saying it was not until October 2015 that he learned that Flint’s drinking water had dangerous levels of lead and not until early 2016 that he became aware of the Legionnaire’s disease epidemic. “As soon as I became aware of it,” Snyder said, “we held a press conference the next day.”

However, Tim Walberg, a congressman from Michigan and member of the House Oversight Committee confronted his fellow Republican with documents indicating that senior state environmental and communications officials were emailing about concerns regarding a Legionnaire’s outbreak in Flint back in March 2015.

The Detroit Free Press, reporting on documents obtained by Progress Michigan, a watchdog group, cited a March 10, 2015, email from the environmental health supervisor of Genesee County, where Flint is the most populous city, saying that the dozens of Legionnaire’s cases diagnosed at the time “closely corresponds with the timeframe of the switch to Flint River water.” (The bacteria that causes Legionnaires is naturally occurring in many water systems across the country, and one water expert believes the switch over likely exacerbated an existing bacterial issue with the supply.) The supervisor characterized the epidemic as a “significant and urgent public health issue” and said the information was “explicitly explained” to Snyder’s environmental quality officials.

This month, the online investigative news site The Intercept detailed a series of back-and-forth phone calls dating back even earlier, to October 2014, between Snyder and his chief of staff Dennis Muchmore. Those calls occurred at the same time Muchmore was in dialogue with top state health officials, which included a phone call with someone at the Michigan Health and Hospital Association. A special prosecutor characterized that call as “presumably about the outbreak.” That call took place more than a year before Snyder told Congress he had found out about the deadly bacteria.

That same month that General Motors realized that the switch away from the Huron River was corroding new engine parts at its Flint plant. How much logic — or humanity — should it have taken to proactively wonder what the water was doing to residents, especially children, given what it was doing to car parts?

AP Photo / Andrew Harnik

The Detroit Free Press reported that Valerie Brader, senior policy adviser and deputy legal counsel to Snyder, wrote other top aides in an October 14, 2014, email that Flint’s water was “an urgent matter to fix,” and that the supply should switch back to Lake Huron water delivered via Detroit’s regional system. Michael Gadola, then Snyder’s chief legal counsel, responded: “My Mom is a City resident. Nice to know she’s drinking water with elevated chlorine levels and fecal coliform.” Gadola, who today is a Michigan state appeals court judge, agreed Flint “should try to get back on the Detroit system as a stopgap ASAP before this thing gets too far out of control.”

Yet somehow Snyder allegedly knew little or nothing of these discussions swirling about him. Two major reports have concluded the buck stopped with him. A Flint Water Task Force report, which Snyder himself commissioned, said in 2016 that while the state’s environmental agency bore “primary responsibility” for causing the Flint water crisis, Snyder bore “ultimate accountability” for decisions coming out of his office.

Then a 2018 report by the University of Michigan’s School of Public Health concluded Snyder bore “significant legal responsibility” for failing to heed citizen complaints at the outset of the crisis, issue a timely emergency declaration, and wrest control from negligent state environmental and health officials. “Flint residents’ complaints were not hidden from the governor,” the report’s authors wrote. “He had a responsibility to listen and respond.”

Snyder, however, has been so unscathed by what happened in Flint that Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government awarded him a prestigious research fellowship in 2019. But howls from Flint, and an online protest petition started by a Kennedy School alum and signed by nearly 7,000 people forced Snyder to withdraw from the fellowship two days after it began.

The renewed spotlight on Snyder’s role in the water crisis comes at a critical time for those who work for environmental justice. Newly inaugurated President Biden has, on paper, given it unprecedented prominence in his federal agenda. Many nominees for his Cabinet have scored significant victories for communities dealing with pollution, including his nominee for attorney general, Merrick Garland, who would oversee the creation of the first environmental and climate justice unit within the Department of Justice.

Snyder’s blithe attitude about Flint symbolizes the urgency with which a Biden administration must make it clear to politicians and corporations that it is no longer business-as-usual to dump on poor people and communities made up predominately of people of color. At the federal level, Biden promises a Justice Department that will “hold corporate executives personally accountable — including jail time where merited.” That is a heavy lift in a nation where corporate executives largely continue to live large no matter how many faulty planes drop out of the sky, how many defective cars kill people, how many predatory banking practices cause people to lose their homes and life savings, and how many particles of pollution causes cancer and brain damage. CEOs might get fired, they might get fined, but they rarely face bars.

A paper last year by legal scholars from the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Southern California noted “the near disappearance of individual liability, especially for top executives,” in corporate crimes over the last decade. It concluded that “an enforcement regime that is limited in its ability to levy fines at an optimal level must rely on other forms of punishment — such as the imposition of liability on guilty individuals and the top executives who facilitate their crimes — to increase deterrence. Only then will corporate criminal punishment be seen as more than a cost of doing business.”

Similarly, Cary Coglianese and Sierra Blazer of the Penn Program on Regulation at the University of Pennsylvania Law School, co-wrote a 2019 op-ed in The Hill during the height of the scandals surrounding Boeing, after two of its 737 Max planes crashed, killing 346 passengers and crew members. Donald Trump’s Department of Justice had prosecuted lower-level technical pilots for fraud related to the federal approval process of the Max. “Prosecutions of lower-level employees would do nothing to assure the public that incentives at the very top of the organization align with passenger safety,” the pair wrote.

This month, Trump’s Justice Department announced a $2.5 billion settlement with Boeing over the fraud charges. No executive went to jail. Nadia Milleron, who lost her daughter, Samya Stumo, summed up the outcome for the Washington Post: “This is just a blip for Boeing.”

To-date, the Flint water crisis has been a blip for Snyder. Environmental injustice nationally will also remain a blip, if governors and CEOs can keep throwing underlings under the bus while riding off in their limousines. As it now stands, the prosecution of lower-level employees will not assure Flint residents who live with the effects of being poisoned that the law is aligned with their safety.