The land that Elsie Herring lives on, about 60 acres of farmland in southeastern North Carolina, has been in her family since her grandfather purchased the property in 1891 from his former enslaver. Her mother was born and raised there and farmed and cultivated those fields for 99 years. Herring and her older siblings were born and raised on the land, and they continue to live in simple houses and trailers sprinkled throughout the fields.

But there is also an unwelcome guest on the Herrings’ property. In the late 1980s, a hog farm was constructed next door to the siblings’ homes, on a contested portion of land that Herring believes rightfully belongs to her family. The farm, now owned by Smithfield Foods, the nation’s top producer of pork, is relatively small. There are two hog houses where pigs are lined up side to side, butt to head, with little space to move. These houses have slats in the floor that allow swine excrement to fall into troughs below, from which it is pumped into malodorous lagoons just outside the structures. And not 8 feet from the home of Herring’s late mother, separated by a thin strip of trees, are the so-called spray fields — corn fields on which hog manure is sprayed as a fertilizer.

A sprayer soaks a field with liquefied manure and urine from a large-scale hog farm near Wallace, North Carolina. AP Photo / Allen G. Breed

Mists of water and swine feces from the operation make their way to Herring’s property, bringing with them a constant, unbearable odor. All she, her family, and neighbors can do is keep the windows and doors shut, and place air fresheners and scented aerosol sprays around the house to mask the smell. “It’s nice to smell something that smells sweet instead of something that’s just so foul,” Herring told Grist. “You just have to do what you have to do to make life as pleasant as you can and try to stay safe at the same time,” she added, noting that even though masking the odor presents a short-term solution, it doesn’t protect them from inhaling the airborne fertilizer. Herring says she has developed bronchitis due to the inescapable pollution.

“Living near these animals, knowing that they are on my family’s land without our permission and having their waste blown on us, having our air and our water polluted,” Herring said, “is like so many injustices are compounded in one.”

[jumbo-content]

[/jumbo-content]

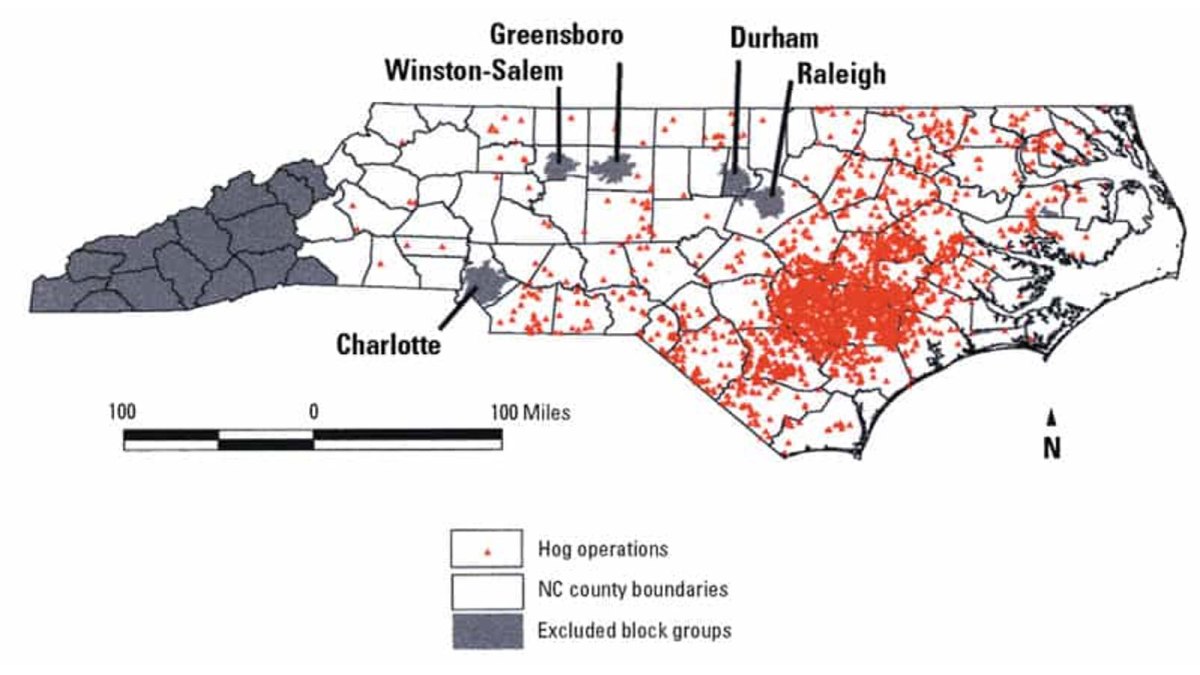

Herring and her family are not alone. There are approximately 2,400 similar hog farms in North Carolina, most of them in Duplin County, where she lives, as well as Sampson, Bladen, and Robeson counties, and lagoons and spray fields are the primary ways these pork farms handle their hog waste.

If the lagoons are left unchecked, the waste that builds up in the pink-tinted waters releases not only extreme odors but methane, ammonia, and other pollutants that can spread into nearby communities. Methane is a greenhouse gas about 86 times more potent than carbon dioxide over a 20-year period, and the other pollutants, like hydrogen sulfide, which is responsible for the odor, can inflame the eyes, skin, and lungs. The smell leaves people reluctant to exit their houses for fear of difficulty breathing — even just to hang their laundry outdoors. The predominantly Black and low-income communities surrounding these farms have experienced increased rates of respiratory and heart disease for decades.

A map shows the location of hog operations in North Carolina, Duplin and Sampson Counties, seen in red near the center, contain the majority of the state’s hog operations. Wing, S., Cole, D., & Grant, G. (2000)

Pork producers say they have a solution, specifically to the methane issue: capturing the gas coming off of these hog lagoons and using it as fuel, a form of “renewable natural gas,” or RNG. The move is pitched as a solution twofer, a win for the community and the climate, too. Environmental advocates and many local residents, however, argue that an investment in so-called biogas will only further perpetuate a practice that harms neighboring communities.

In 2007, North Carolina’s government mandated that 0.2 percent of energy from local utilities operating in the state come from renewable natural gas. Energy providers struggled to make it happen until 2018, when Optima KV, the first successful swine biogas program in the state, was created in Duplin County. This project collected methane from five hog farms and turned it into energy for Duke Energy, the state’s primary electric utility.

Now, Smithfield is partnering with another major utility, the Richmond, Virginia–based Dominion Energy, to complete another biogas energy development in Duplin and Sampson Counties by summer 2021. This endeavor, christened the Grady Road Project and headquartered in the town of Turkey, would connect 19 farms in the area with a pipeline and “produce enough RNG to heat 4,500 homes, or the equivalent of taking 36,000 cars off the road,” said Kraig Westerbeek, senior director of Smithfield Renewables — the pork company’s sustainability department.

Biogas production works by putting covers over hog waste lagoons and collecting the methane that’s created by the microorganisms in pig feces (instead of allowing it to enter the atmosphere). The methane gas is then funneled into pipelines — approximately 30 miles of them for the Grady Road Project — that transport it to what will be a newly constructed natural gas processing plant. The processed gas can then be injected into an existing natural gas pipeline and be used as an energy source in individual homes and businesses, as well as power plants. Smithfield says that covering lagoons will not only reduce methane emissions but also the terrible odor caused by other gases produced by pig feces. And because the process reduces greenhouse gas emissions from animal waste, renewable natural gas collected from hog farms can be counted as carbon offset credits for utilities like Dominion that are pledging to go carbon neutral.

An aerial view of a German biogas power facility adjacent to a dairy farm. Sean Gallup / Getty Images

The Grady Road venture is just one of the renewable natural gas systems that Smithfield and Dominion are planning across the country through their Align RNG biogas creation program. In December, Smithfield announced the completion of its first Align RNG system in Milford, Utah. It also has plans to bring Align to Virginia in 2022.

Smithfield claims that the Grady Road Project would be a boon to communities in North Carolina by providing an extra income stream to participating farmers, creating construction jobs, and reducing waste odor. “The bottom line is that this project is good for the environment and a win for local farmers, communities, and energy consumers,” Westerbeek said.

In January, the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality, or DEQ, approved Smithfield’s most recent air quality permit application for the $30 million project. To move forward with the project, each of the 19 farms involved now must receive additional permits. DEQ held a public meeting in late January to discuss permit modifications for four of the 19 farms. Yet public concerns over a lack of transparency about the Grady Road Project dominated the meeting.

Environmental advocates and people who live near the Grady Road Project site say that collecting biogas won’t reduce most of the pollution involved in industrial hog farming. They say Smithfield’s endeavor therefore amounts to greenwashing.

Ryke Longest, co-director of Duke University’s Environmental Law and Policy Clinic, pointed out to Grist via email that Align RNG enables Smithfield and Dominion “to greenwash carbon pollution through offsets” and make “money off one problem” while leaving the others unsolved. Hog farming produces a lot of pollutants besides the methane harvested by biogas projects. These include ammonia, hydrogen sulfide, fine particulate matter, and other volatile organic compounds. “Align RNG only controls one of these pollutants,” Longest wrote.

Some hog lagoons in North Carolina, specifically older pits, are unlined, meaning that there is no protective layer, usually hard clay, that separates the wastewater from the underlying soil. Westerbeek said that Smithfield’s existing lagoons are “in fact lined and are recognized as so by the state of North Carolina.” But during heavy rains or severe weather events, these lagoons often still overflow. That wastewater, filled with nitrates that have been linked to increased miscarriages, infant mortality, and blue baby syndrome, can seep into groundwater. Biogas operations could actually make hog farms’ pollution problems worse, as a DEQ environmental engineer acknowledged during the recent public hearing. Covering lagoons is believed to increase concentrations of ammonia in the fuchsia waters.

An aerial view of an industrial hog farm operation and waste lagoon in Sampson County near the South River tributary, less than 30 minutes out from Clinton, North Carolina. Matt Butler / Sound Rivers / Waterkeeper Alliance Inc.

“Most of these communities are communities that are also on well water,” said Sherri White-Williamson, the environmental justice policy director for the nonprofit NC Conservation Network. “Oftentimes, they’re in situations where there are days when they can’t use the water that comes out of their well because it is so badly polluted.”

The ammonia from hog operations is also connected to increased fish kills in local waterways. In July, thousands of fish were killed downstream of hog operations after millions of gallons of feces were washed into the nearby Cape Fear River basin, leading to pollution, harmful algal blooms, and oxygen depletion in the water. In December, a similar spill occurred when about 1 million gallons of untreated hog waste leaked from a hog lagoon operated by a DC Mills Farm into the Trent River.

“Farmers are required to document all activity that could potentially strain the lagoons, such as rainfall and lagoon integrity,” Westerbeek told Grist in response to concerns over water pollution from Smithfield’s lagoons. “Liner conditions are periodically monitored and inspected by the state.”

Even before the Grady Road Project, Smithfield promised to address health concerns associated with its hog farms. In 2000, the company entered into an agreement with North Carolina’s attorney general to invest in “environmentally superior technology” that would convert its primitive waste management systems, like the lagoons, to something safer. The Raleigh News and Observer reported in December that Smithfield still hasn’t fulfilled its end of the bargain, and Elsie Herring believes the reason is financial. “They invested all this money to identify new systems, then they say it’s too costly to implement them,” she said. “So their main goal, in the past and now and in the future, is making more money, more money, more money.”

According to Longest, the company has not yet committed to doing any additional waste treatment beyond covering its North Carolina lagoons to capture methane. And the lagoons are only part of the problem. “This will do nothing to minimize spraying,” Cape Fear Riverkeeper Kemp Burdette told the Waterkeeper Alliance about the use of hog waste as a crop fertilizer.

Westerbeek responded to criticism about spray field fertilizers, saying they are applied at controlled rates and that detailed records of each farm are kept for state inspection. “There is nothing in manure that hasn’t already gone through the digestive system of an animal. It is not pollution. Referring to it as so is inaccurate,” said Westerbeek. “Farmers rely on the nutrient value of manure to fertilize their crops, which is why this project does not and should not eliminate the application of nutrients on local farms and why the state recognizes land application of these nutrients as a hog farming industry practice.”

Environmental advocates and residents oppose the continued use of lagoons and spraying, but they will settle for Smithfield implementing techniques known as “advanced nitrification/denitrification” or AND, which reduces the amount of nitrogen and ammonia created and released from lagoons. Smithfield reportedly already uses AND techniques in some of its Missouri operations. In response to a question about why it doesn’t implement these technologies in North Carolina, Westerbeek said that its operations are in compliance with state regulations. He also said that it is unfair to compare the AND techniques used in other states to the company’s practices in North Carolina because the state’s hog farms are smaller than those in Missouri and there are “dramatically different climate conditions” between regions.

For residents and advocates, Smithfield’s refusal to consider stronger pollution controls is proof that its biogas plans are really about profit, not community protection. “They say there is no harm because they’re covering the lagoons,” Herring told NC Policy Watch last year in reference to a nuisance lawsuit she’s filed against Smithfield. “But this just enables them to do business as usual.”

Young hogs, as seen through a gate, on a North Carolina industrial farm Gerry Broome / AP Photo

Hog farms contribute to an outsized pollution burden faced by nearby communities who are contending with many more environmental hazards.

In Robeson County, a predominantly Black and Indigenous community, residents are also grappling with air pollution from the local wood pellet industry, which cuts down trees and compresses them to be used as biomass energy for many countries in Europe. Air and water quality are also threatened by coal ash waste sites from Duke Energy’s W.H. Weatherspoon Power Station, which retired three coal-fired generating units in 2012, not to mention the Robeson County landfill. In Sampson County, right next to the Duplin-Sampson County borderline and along the path of the proposed Grady Road pipeline, residents already live less than a quarter-mile from the heavily trafficked Interstate 40. Many are also in close proximity to a Butterball processing plant, poultry and hog farms, and a local trash dump.

“You’re looking at communities that wouldn’t just have this new biogas processor, but it’s going to have all of those other polluting facilities,” said White-Williamson, noting that when the NC Department of Environmental Quality issues air permits to projects like this, they do not account for the pollution stemming from neighboring facilities.

Biogas may only add to the existing odor and air pollution burden. When the methane gas from hog waste is processed into a usable form, carbon dioxide is released. Smithfield predicted in documents submitted to the Division of Air Quality that the central gas processing plant it wants to build in Turkey will produce more than 60 tons of emissions each year, according to NC Policy Watch.

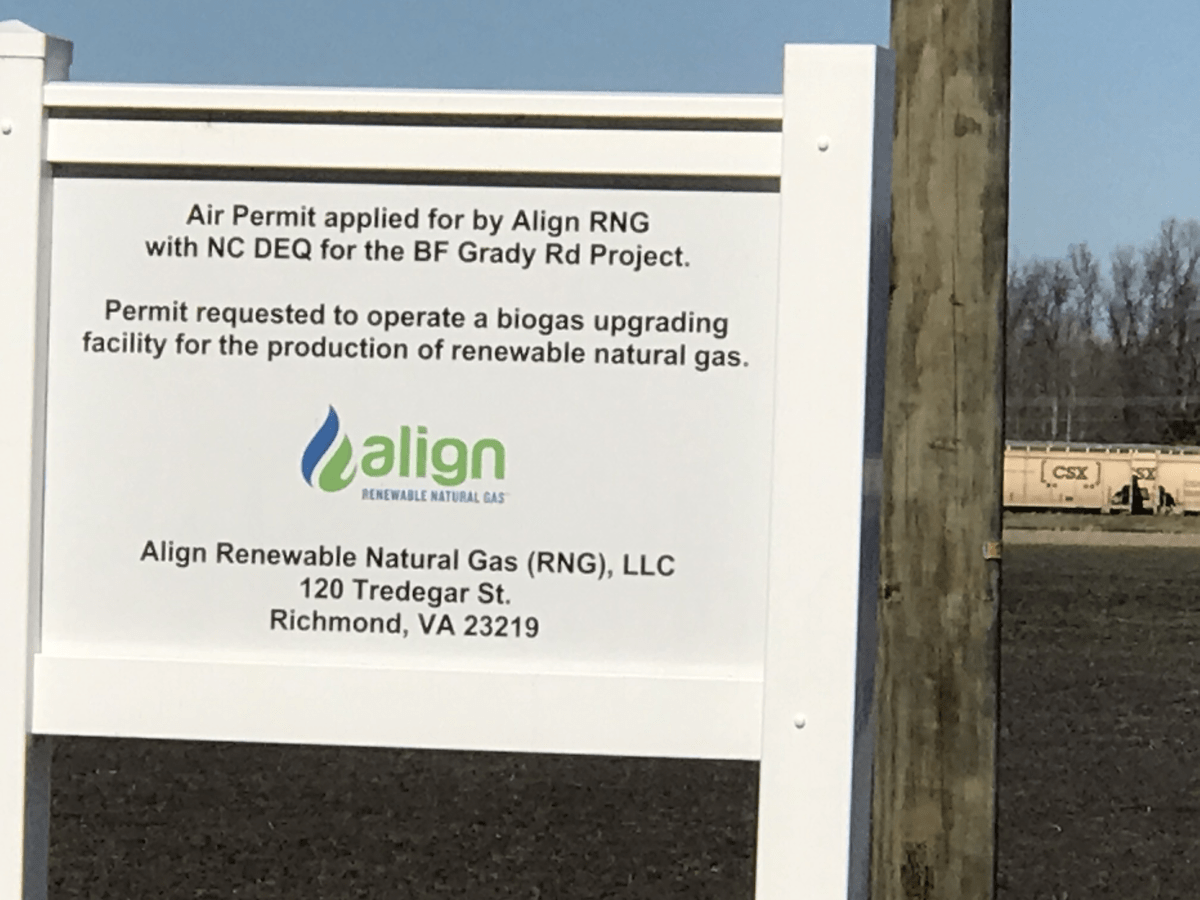

An Align RNG sign located at the entrance to Highway 24, indicating the location of the proposed Grady Road Project biogas site. Courtesy of Sherri White-Williamson

Prior to a public hearing last November concerning air permits for the Grady Road Project, Smithfield sent out what White-Williamson described as a “nice, glossy, four-page, well-produced propaganda piece” to those communities that would be impacted by the Align RNG construction. Around the same time, White-Williamson said a small 3-by-4 foot sign appeared at the entrance to Highway 24, difficult to see unless “you were driving slow” and knew what you were looking for. For some, this was the first indication that the project was even happening. Then, at the hearing, Smithfield shared the locations of only four of the 19 farms involved in the project. Despite the company’s outreach, White-Williamson says most of the residents in the pipeline’s path were unaware that the project was happening.

“It is being sold as just a win-win kind of solution, and yet, there is a severe lack of transparency when it comes to educating and informing the public — even the community in which it’s going to be located — about the details of the project,” said Brian Powell, the communications director for NC Conservation Network.

Westerbeek said that it is “both surprising and concerning” that some residents feel that Smithfield has not been transparent about the project, stating that Smithfield has “proactively engaged the community over the last 18 months and received notable support.” Outreach included sending out mailers like the one White-Williamson referred to, as well as publishing ads in local newspapers, holding virtual town halls, and hosting an open house in summer 2019.

With regard to hog farm locations, Westerbeek said that all North Carolina hog farm locations are “publicly available through the DEQ.” However, in December, the agency sent a letter to Smithfield asking it to share the locations of all the farms that will be connected to the Grady Road Project, a request that Smithfield denied on the grounds that the information was outside the purview of its air permit request. When they asked again, Smithfield responded almost three weeks later, once again refusing their request. DEQ approved the permit anyway, and residents have still not received any information on the locations of all the farms that will be participating in the project or the exact renewable natural gas pipeline itself.

This is not a new pattern. For years, community members and environmental organizations like the Waterkeeper Alliance have reported hog farm violations, like illegal spraying and dumping waste into ditches and streams, to the DEQ. But the agency has often said there wasn’t anything it could do. And White-Williamson said it’s common for the DEQ to approve permit applications for hog farms without all the requested location or emissions information.

When DEQ Secretary Michael Regan, who was recently nominated to be President Joe Biden’s Environmental Protection Agency administrator, was appointed to the position in 2017, communities had hope for a change in the system. At first, the DEQ did issue deficiency notices to several farms, and it also agreed to settlements with advocates and community members in which it promised to be tougher on hog farms. Many in the community, White-Williamson included, are still waiting to see this more aggressive regulatory oversight.

“If the department decides they need more information, they request that information, and then the industry basically says ‘hell no,’ and you issue it anyway,” White-Williamson said. “That gives the industry the impression that they can do whatever they want.

“What’s the point of having a Department of Environmental Quality?”

The renewable natural gas that would flow through the Grady Road Project tends to be more expensive than conventional natural gas. But Randy Wheeless, a spokesperson for Duke Energy, which invests in biogas from the previously completed Optima KV project, told Grist that RNG has an added benefit — it represents an attempt to make the best of an unpleasant situation. Covering hog farm lagoons not only allows for the harvesting of methane, but it also eliminates the smell from the waste ponds, he said.

Waste from hogs owned by Smithfield Foods flows into the waste pond at a farm in Farmville, North Carolina. Gerry Broome / AP Photo

“Biogas is definitely more expensive than regular natural gas” — around eight times more expensive, Wheeless said. “And so if we were going just by economics alone, renewable natural gas would be a tough sell.” He added that the only reason Duke Energy is investing in biogas is because of the state mandate.

Despite its economic limitations, new swine biogas operations are sprouting up in states like Missouri, Utah, and Virginia. And renewable natural gas from poultry litter and dairy farms has been developing in states like California, Maryland, and New York. At the same time, operations in Colorado and Michigan have been shut down due to complaints of severe odor during processing, waste seepage, and explosion risks.

Environmental nonprofits and communities have not completely ruled out these energy sources as solutions to the climate crisis and to local environmental health issues. But they’re calling for systems that operate using the best available technology to reduce pollution — without lagoons and spray fields — and operations that are informed by community input and greater attempts at transparency.

“If there were a way to reduce the number of hogs or the manner in which the hogs are raised in those areas, that could help reduce some of the impact in the communities,” said White-Williamson. “If the industry just tried to treat people who live in those communities like human beings, that would help.”

Herring, who has been contending with the smell, flies, and buzzards of hog farms since the 1990s, made a similar point. “Why should anyone have to live like this?” she asked. “Why can’t they ask themselves that question: Would they want this done to them?”