In the rolling Appalachian foothills of Ohio, Sunday Creek runs bright with shades of red and orange. The 27-mile-long tributary flows through the ruins of abandoned coal mines, which sprawl beneath the southeast part of the state like a labyrinth. The companies that dug the century-old mines are long gone. But residents in this rural region still live with the mess that’s left behind.

The creek’s vibrant colors are from “acid mine drainage,” which spills into watersheds nationwide. Iron sulfides from the mines react with air and water, forming acidic runoff. In high concentrations, it can kill aquatic life and contaminate drinking water. Communities and government agencies spend millions of dollars on cleanup every year, but the problem is so pervasive and expensive that many streams remain polluted.

At Sunday Creek, a broad group of locals have found a way to help foot the clean-up bill: by turning mine pollution into eye-catching paints.

A set of tanks and tubs sits near the grassy creek banks in Corning. Once a hub of coal mining and railroad jobs, the village of 600 people is pockmarked with old mine sites. Guy Riefler, a civil engineering professor at Ohio University, developed the water treatment plant there over the last decade, working with students, researchers, and the local nonprofit Rural Action.

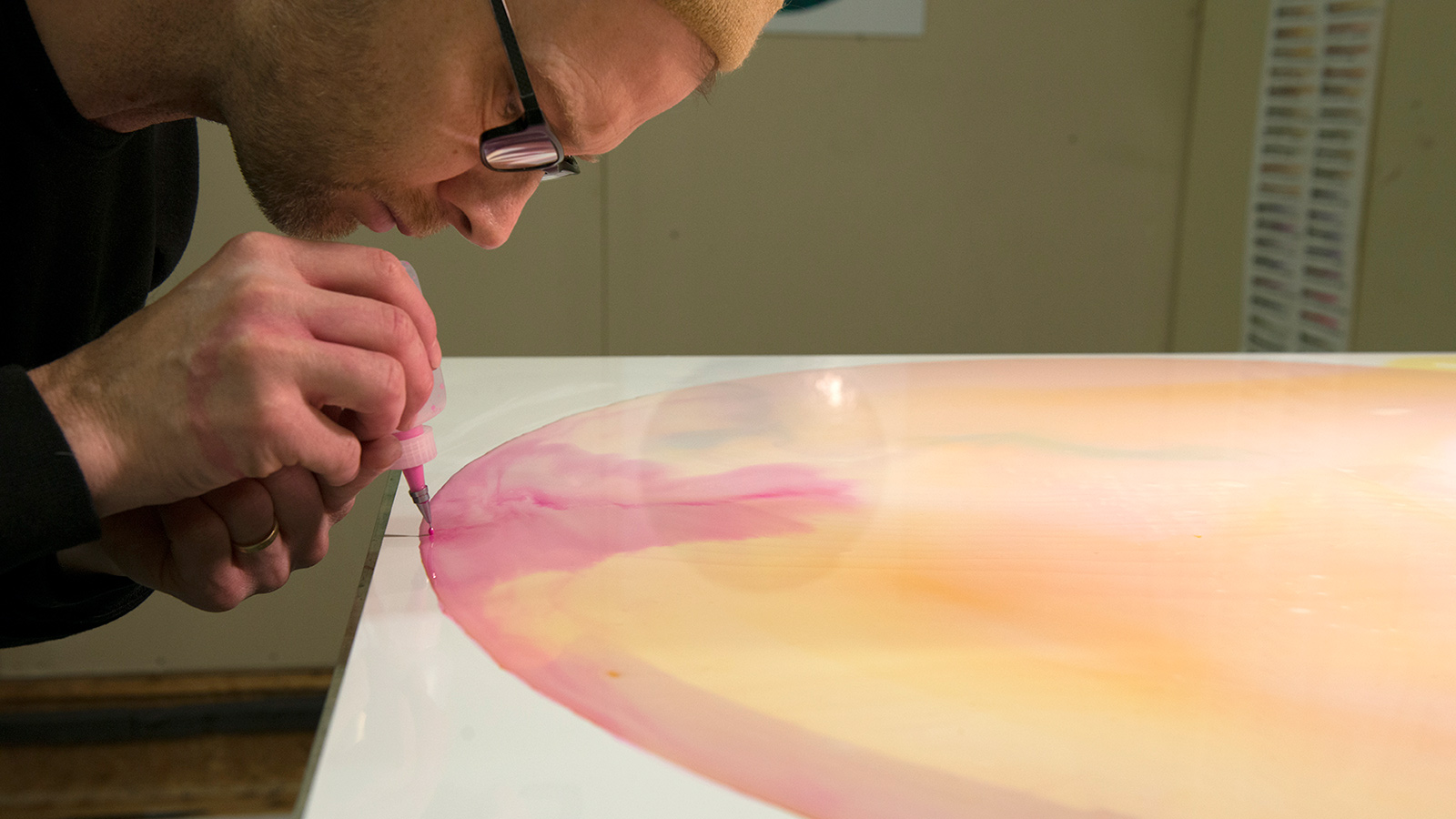

In three steps, the pilot plant captures runoff from a mine seep, then uses oxygen and bacteria to separate iron from the water. The metal settles and forms a sludge, and the clear, filtered water returns to the creek. Riefler then hauls the sludge to the university campus in nearby Athens. John Sabraw, an artist and OU professor, washes, dries, and bakes it in kilns, producing bricks of brown ochre, rusty red, and earthy violet pigments for paint.

The team recently began shipping pigment to Gamblin Artist’s Oil Colors, a wholesale paint manufacturer in Portland, Oregon. The company says it tested the products and found them to be as safe as other pigments made from iron oxide. This spring, Gamblin will start selling oil paints from Sunday Creek pigments nationwide.

“By processing it in a way that we can now sell it, we’ve totally flipped the perspective,” said Michelle Shively, who oversees efforts to clean up Sunday Creek for Rural Action. “We’ve created a valuable commodity out of the waste product.”

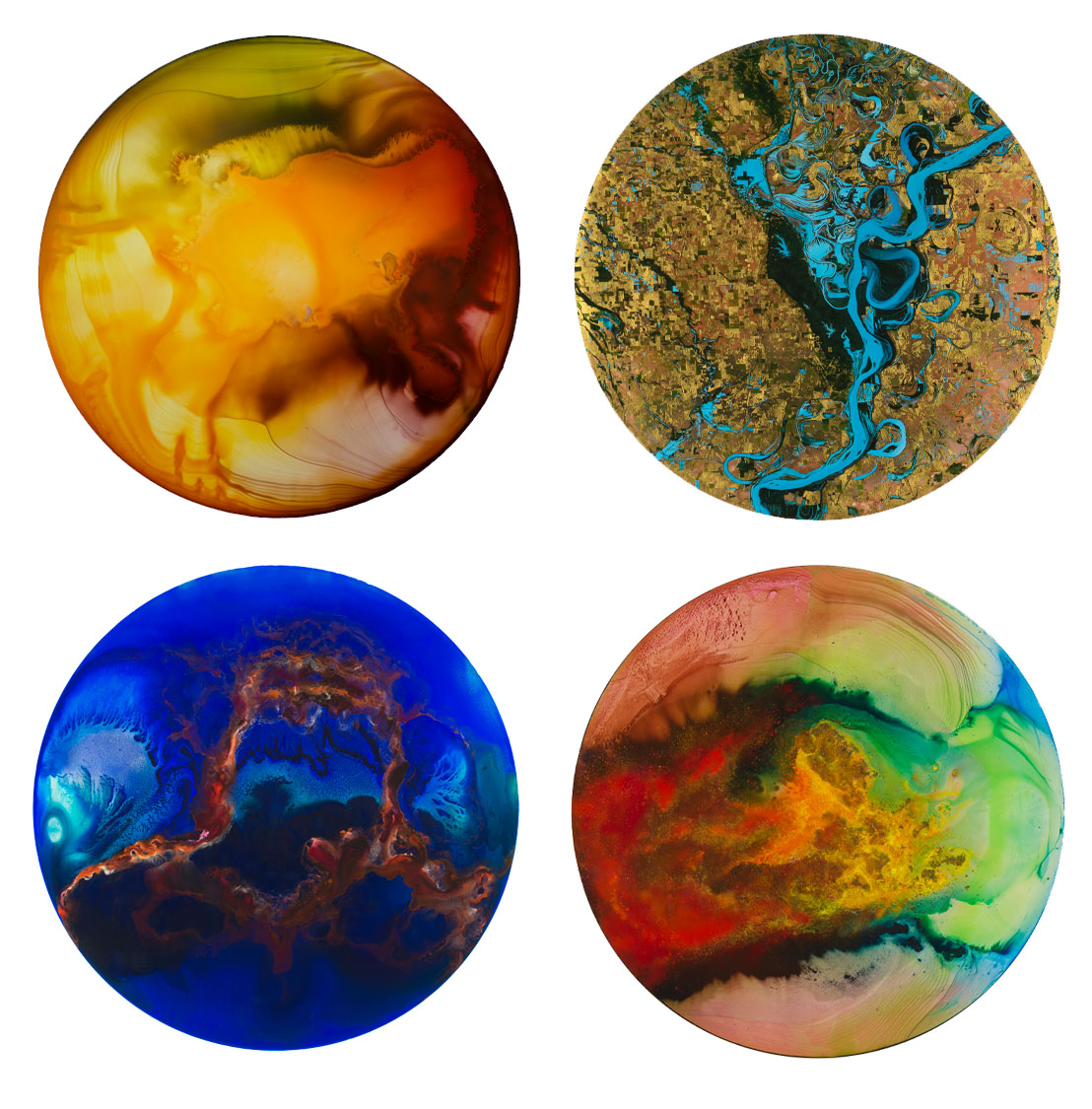

Paintings from Sabraw’s Chroma series. Grist / John Sabraw

In December, the Ohio Department of Natural Resources awarded the partners $3.5 million to start building a full-scale water treatment plant in nearby Millfield, a short drive south of Corning. A 23-square-mile network of abandoned mines sits beneath Millfield, spewing 7,000 pounds of iron into Sunday Creek every day. Once completed, the new plant could produce up to 2 million pounds of iron oxide pigments a year and restore the creek to health, Riefler said. He expects to have it up and running as soon as next year.

Across the country, tens of thousands of abandoned mines from the 19th and early 20th centuries remain. Old coal sites can collapse, cause landslides, clog streams, or release hazardous gases. Federal agencies say it’s hard to know precisely how many sites exist or where, since old mines weren’t adequately tracked. New problems constantly emerge; after heavy rains, underground mines sometimes flood and burst open.

“The challenge facing the nation today is a costly, sometimes unpredictable problem that could threaten the health, safety, or lives of people in or near coal field communities,” said Sara Eckert, a spokesperson for the Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement, in the U.S. Department of Interior.

States are responsible for dealing with abandoned mines, and they rely primarily on federal funding to address the many public health and safety concerns those sites pose. Their to-do lists remain long. As of September 2018, states had identified an estimated $10.1 billion worth of projects that still need funding, according to a national inventory.

Ohio has invested more than $30 million since the mid-1990s to treat acid mine drainage, yet pollution persists in dozens of sections of watersheds, according to the Ohio Department of Natural Resources. The agency operates over 40 acid mine drainage treatment systems in the state, the majority of which use artificial wetlands, settling ponds, and other passive methods to clean the water.

None are quite like the Sunday Creek project. Riefler said the water treatment plant initially “limped along” with little research funding. That changed after Sabraw joined the effort in 2009. The artist improved the quality of the paint pigments and drew attention to the project through his artwork. In his paintings, colors from Sunday Creek pollution swirl and shimmer on aluminum panels, conveying “the psychological and emotional ties that we all have to nature,” Sabraw said.

The team also raised money through Kickstarter, which netted more than $33,000 in April 2018. To support the campaign, the art company Gamblin made 500 tubes of “iron violet” oil paint from the pigment for the team to sell.

Acidic runoff from an abandoned coal mine seeps into Sunday Creek near Corning, Ohio. In the distance, acid mine drainage bubbles into the creek. John Sabraw

Now, with a full-scale plant in the works, the partners are looking to push their products beyond the art world. Shively said their goal is to sell enough iron oxide pigments — for use in house paints, industrial coatings, and construction materials — to cover long-term operation and maintenance costs at the Millfield plant. They also hope to replicate the project across Appalachian Ohio, one of the poorest parts of the state.

Companies in neighboring Pennsylvania have been successful at funding cleanup costs by selling products made with pollution. Environ Oxide and Clean Creek market earth-tone pigments from recovered iron oxide for house paints and pottery glazes. Those projects use iron that already entered rivers and wetlands. The Sunday Creek plant is the first to make pigments from iron captured at the source, Riefler said.

Rural Action, the Ohio nonprofit teaming up with Riefler and Sabraw, has launched a for-profit business to manage the next phase of the project. Even with the $3.5 million state grant, the team will need to raise another $4 million to complete the full-scale water treatment facility in Millfield. Shively said it could eventually employ up to six people, a boost to the tiny town’s tax base. A cleaner Sunday Creek might also mean that locals can return to fishing and swimming in waters now tarnished by Day-Glo pollution.

“Having a clean stream that doesn’t run orange through your community can make you feel better about the place you live,” Shively said.