Chicago’s Little Village neighborhood sits on a scant 4 square miles on the southwest side of the city, but it packs a lot into that modest footprint. With a population density similar to New York City’s, the immigrant-rich enclave, sometimes known as the “Mexico of the Midwest,” includes the largest single-site jail in the country, a recently shuttered coal-fired power plant turned massive warehouse development, and Chicago’s second highest-grossing shopping district.

It is also home to the city’s worst coronavirus hotspot.

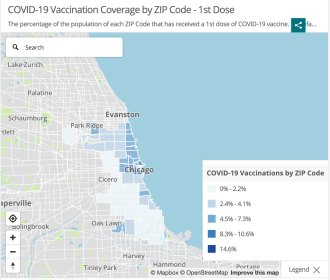

According to an analysis of data released by Chicago and the state of Illinois in January, residents in Little Village’s 60623 and 60608 ZIP codes are up to 15 times more likely to die from the coronavirus compared to their Near North Side and downtown counterparts. Yet they have received 20 percent fewer vaccinations than the city’s more affluent downtown communities.

“I like to call this environmental trauma because you’re getting hit with so many things over and over again,” said Jeremiah Muhammad, a South Side native who works on water-related issues throughout Chicago and Illinois with the Little Village Environmental Justice Organization, or LVEJO.

The coronavirus pandemic has thrown into sharp relief the toll decades of environmental injustices have taken on poorer communities of color. That’s something the Biden administration has signaled it wants to work on: On Wednesday, the president signed an executive order creating a new White House council on environmental justice, and pledged that 40 percent of the benefits from federal investments in clean energy and clean water would go to communities that bear disproportionate pollution.

But if Little Village is any indication, it’s going to take a lot more than a presidential decree to convince residents the government has their best interests at heart. “We have a huge issue around trust, especially being an immigrant community, we have to organize around a lot of different things — ICE, water access, poverty,” Muhammad said. “You have these prejudices and racism coming in from government entities, which plays a part in why Little Village and other surrounding communities are treated so badly compared to other communities in the city.”

A woman poses for a portrait inside her Chicago home in May 2020 while quarantining with her COVID-positive husband and daughter. Armando L. Sanchez / Chicago Tribune / TNS

Chicago sometimes touts itself as “the most American of American cities.” The nickname is intended to be a reference to the city’s gritty, go-getter attitude, its so-called melting pot of cultures. But to many low-income residents and people of color, that superlative doesn’t come off as a compliment so much as a constant reminder of the many decades of structural inequities now amplified by the coronavirus pandemic.

Little Village was largely shaped by Chicago’s segregationist housing policies. In the 1950s and 1960s, Black and Latino families were pushed out of Northern neighborhoods and into the area, limited by where they were permitted to buy houses. When Martin Luther King, Jr. visited Chicago in 1965, he set up his temporary residence in nearby North Lawndale, in part to highlight the city’s race-related disparities in housing. Today, Little Village’s population is 88 percent non-white (58 percent Latino and 23 percent Black).

The area’s economic hardships also go back several decades. In 1979, the Little Village community was home to around 1 million industrial jobs, primarily in the meatpacking, steel, and manufacturing industries. But by the mid-1980s, 37 percent of those jobs had been eliminated. The loss of those comparatively stable union jobs was devastating, squeezing many residents into low-wage, temporary jobs.

But even as the jobs disappeared, the industries left a lasting mark on the community’s health. A 2001 study from the Harvard School of Public Health attributed 41 premature deaths, 2,800 asthma attacks, and 550 emergency room visits annually to the neighborhood’s old Crawford and Fisk coal plant. Community groups including the Little Village Environmental Justice Organization fought for years to have the plant shut down, a goal they eventually achieved in 2012. But the site, contaminated with waste including lead, selenium, and arsenic, sat untouched until 2017, when the city council rezoned the area for high-end commercial and tech development.

The shuttered coal-fired Crawford power plant, seen here in 2017, remained idle in the Little Village neighborhood of Chicago from 2012 until 2020. Scott Olson / Getty Images

Community relief over the coal plant’s removal was short-lived: The city soon announced that a warehouse development, expected to bring hundreds of diesel fuel trucks every day, would be constructed on the same site. People who lived nearby were worried about the trucks’ impact on air quality. A 2018 study by local high school students in Little Village found that on average 90 diesel trucks per hour drove through the community’s main road, with more expected once the development was completed in 2021.

The neighborhood’s environmental woes weren’t limited to the air: When the last remnants of the former coal plant were demolished last April, during the initial throes of the coronavirus pandemic, the implosion sent large dust clouds floating through the streets for hours. Local activists say the blast rocked the lead service lines that run through the community, potentially allowing harmful materials to seep into residents’ water. (Chicago has approximately 400,000 lead service lines, more than any city in the country.)

In 2018, the National Resources Defense Council created a map of Chicago outlining these kinds of environmental burdens and pollution. The map illustrates the cumulative vulnerabilities in Little Village and other nearby southwest communities, as well as on the Southeast Side. Little Village falls into the range of highest burden. The nearby downtown communities, which are more than 70 percent white, fall into the least burdened range.

NRDC

“The question is always: why aren’t resources going towards the communities that need it?” said José Acosta-Córdova, an environmental planning and research organizer at LVEJO. “And in Chicago, environmental justice is where all of the struggles — economic justice, racial justice, immigration, labor issues — meet.”

Leadership Development for the Sustainable Self Determination of Little Village

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, it became clear that the neighborhood’s environmental woes were exacerbating the local health risks associated with the disease. An LVEJO study of the years leading up to the pandemic found Little Village residents were already about 1.2 times more likely than average to have their water shut off compared to the rest of the city — and 52 times higher than the Near North Side.

In March 2020, the Illinois Commerce Commission announced an emergency moratorium on all utility shutoffs during the pandemic, but an investigation by the Intercept found at least 16,165 Illinois households had utility shutoffs in September alone. (A recent National Bureau of Economic Research study estimates that a national moratorium on these kinds of shutoffs since the onset of the pandemic could have reduced all infections by 9 percent and deaths by 15 percent.)

And the neighborhood’s COVID-19 rates kept climbing. In November, hundreds of cars were lining up every day at the largest local drive-through testing site, according to one local news report. One in nine residents had a confirmed case of COVID-19.

The city’s vaccine rollout plan did not seem to take these high infection rates into account, prioritizing those with specific jobs over those with place-based risk. But in Chicago, poverty and race strongly correlate with one’s proximity and access to health care and employment. While the city’s decision about which groups to vaccinate first followed guidelines set at the federal level, it put many residents of Little Village at a disadvantage because of the high local unemployment rate — as much as three times that of the city’s wealthier neighborhoods.

“This is the way the city has been set up for decades, especially since deindustrialization, these communities have been neglected,” said LVEJO’s Acosta-Córdova, whose family’s roots on the West Side of Chicago go back 70 years. “And now during a respiratory pandemic, our communities on the frontlines of dealing with respiratory issues and air quality issues aren’t being given access.”

Demonstrators in a car caravan gather across from the shuttered Crawford Power Generating Station in the Little Village neighborhood of Chicago as part of an Earth Day to May Day in April 2020. The sign translates to “Little Village breathes.” Max Herman / NurPhoto

While the pandemic has exacerbated old racial and income-related disparities, some activists hope it has also ushered in an opportunity for the city to try to address these inequalities now that they have once again come to light.

During a January 2021 press conference, the Chicago Mayor’s office announced they were in the planning stages of launching a “community engagement effort” around COVID-19 vaccination on the South and West Sides. The city has also begun prioritizing residents by age — starting with those over 65 years old — along with certain essential workers like police, teachers, and bus drivers.

City of Chicago. January 2021

But the numbers are still damning. The New York Times’ vaccine distribution tracker ranks Illinois 47th out of 50 states for percentage of the population that has received at least one dose of the vaccine, and 43rd in the U.S. for the percentage of doses used. According to a press conference given by Dr. Allison Arwady, commissioner of the Chicago Department of Public Health, Chicago’s public vaccination sites are fully booked — but only with health care workers who have been eligible for seven weeks, not individuals based on age. And a recent report found that employers of essential workers in Chicago say they have received little to no information from the city about how to go about vaccinating employees or when more vaccines will be available.

Grist reached out to the mayor’s office for comment, which directed the request to the Chicago Department of Public Health for comment. CDPH did not respond by time of publication.

Acosta-Córdova said access to resources like clean air, water, and now vaccines are why people need to keep these environmental injustices in mind when making future policy decisions. “These issues have been in Chicago for much longer than the idea of ‘environmental justice’ but framing these issues around environmental justice helps groups — Black, Latino, and Indigenous in particular — rally and bring all of our struggles together,” he said.

Acosta-Córdova and LVEJO have continued to hold regular community dialogues about environmental justice, encouraging residents to get tested and advocating for currently eligible workers and residents to schedule vaccination appointments, but there is only so much the organization can do, he told Grist. It’s up to the city, he said, to redefine its values and reframe its ideas about which communities are “essential.”