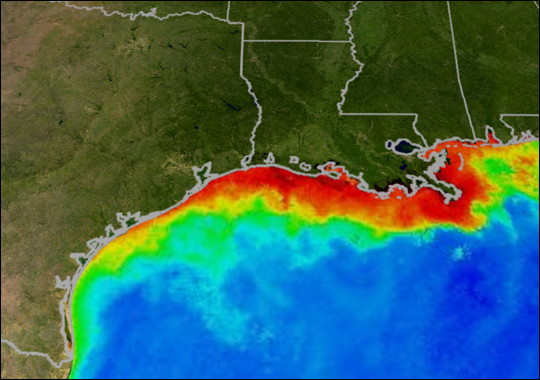

Here’s last year’s Gulf dead zone. How big will this year’s be? (Photo courtesy of NOAA.)

If you’re an underwater creature living in the Gulf of Mexico, summer is not your friend. All spring long, rain falls on America’s farmland and floods the waterways around factory animal farms, creating a steady stream of nitrogen from excess fertilizer and animal waste that heads down the Mississippi River and out to the Gulf. These nutrients create algae that sinks, decomposes, and eats oxygen. The result is an oxygen-free area or underwater desert — a dead zone.

This year, one study from the University of Michigan estimates the Gulf dead zone might be a lot smaller than it has been in recent years — a mere 1,200 square miles, compared to 6,765 square miles in 2011.

If this turns out to be the case, it won’t be the result of improved agricultural practices, but rather the result of what Reuters calls the Corn Belt’s “driest season in 24 years.” The article continues:

… this growing season is reminiscent of the summer of 1988, when the central Corn Belt had significant crop losses. Field conditions were hot and dry early this spring, similar to what happened 24 years ago when local crops, especially corn, were disseminated by lack of summer rains.

“Clearly it’s one of these nasty droughts. If it doesn’t surpass 1988, it certainly is going to rival it or be among the so-called great droughts we’ve had in the past 30 years,” said Bob Nielsen, extension agronomist at Purdue University.

Much less rain means a lower Mississippi River (17 feet below average for this time of year) and, most likely, fewer damaging nutrients washing into the Gulf.

But the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has a different projection. It’s using data from Louisiana State University that “accounts for the possibility of stored nutrients in the northern Gulf, such as in bottom sediments.” For this reason, it’s betting on a dead zone nearly as big as last year’s.

We won’t know the size of the disaster zone until researchers make an official announcement around the beginning of August.

In the meantime, some scientists are pointing out that while a smaller dead zone may give aquatic life in the Gulf a brief chance to rebound, our farm landscapes are still loaded with nitrogen.

“These dead zones are ecological time bombs,” Donald Scavia, professor at the University of Michigan School of Natural Resources and Environment, told Futurity. “Without determined local, regional, and national efforts to control nutrient loads, we are putting major fisheries at risk.”