Are there GMOs in your breakfast?Did a recent scientific study just change the way we should think about the safety of genetically modified foods? According to Ari Levaux at theAtlantic, the answer is a resounding yes.

Are there GMOs in your breakfast?Did a recent scientific study just change the way we should think about the safety of genetically modified foods? According to Ari Levaux at theAtlantic, the answer is a resounding yes.

The study in question, performed by researchers at China’s Nanjing University and published in the journal Cell Research, found that a form of genetic material — called microRNA — from conventional rice survived the human digestive process and proceeded to affect cholesterol function in humans.

Levaux argues that this new study “reveals a pathway by which genetically modified (GM) foods might influence human health” which should cause us to completely revisit the question of GM crops’ safety. And he’s right to be alarmed, just a little off on the reasoning.

Let’s take a closer look at how this study applies to current GM technology, shall we?

I would argue that several studies have already suggested that existing GM foods might present a health risk. For example, this study in The International Journal of Biological Sciences found evidence that Monsanto’s Bt corn causes organ damage in lab animals. Then there’s this one which showed that GM soybeans can alter mice on the cellular level — an indication that genetically modified material survives digestion and is active in animals that consume it.

Of course, advocates of genetically modified foods will observe that the phenomenon of genetic transfer through consumption applies to all plants and that GM foods are therefore “substantially equivalent” to non-GM foods. As Levaux explains at length, this concept of substantial equivalence has been used by the biotech industry as well as our government to push GM foods through safety testing with minimal scrutiny. What’s Monsanto’s defense of all this? On its website, the company claims:

There is no need to test the safety of DNA introduced into GM crops. DNA (and resulting RNA) is present in almost all foods … DNA is non-toxic and the presence of DNA, in and of itself, presents no hazard … So long as the introduced protein is determined to be safe, food from GM crops determined to be substantially equivalent is not expected to pose any health risks.

So the fact that the Chinese team found active genetic material going from plants to humans isn’t really new and doesn’t really change what we know about how existing genetically engineered crops might affect us.

But what is new — and what Levaux missed — is that the Chinese study happens to involve exactly the kind of genetic matrieral — microRNA — that biotech companies hope to use in their next generation of genetically modified foods.

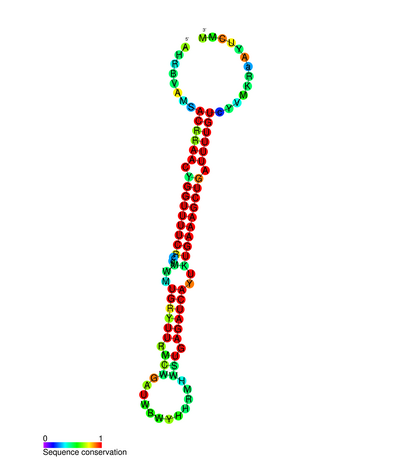

Today’s GMOs are almost entirely based on adding new genes to crops like corn, soy, and cotton in order to alter the way the plants function. And even then new functions are mostly limited to making plants either able to tolerate herbicides or to produce their own. But if biotechnology companies are successful in their efforts, there may soon be genetically modified foods that use microRNA — simply put, snippets of RNA whose potency were only discovered around a decade ago — to target, and block the function of specific genes in pests.

Thus the news that plant microRNA can survive digestion and affect human systems brings into question the wisdom of pursuing this kind of technology in food.

As explained to me by Doug Gurian-Sherman, senior scientist for the Union of Concerned Scientists and expert in genetically modified foods, microRNA technology is an area that biotech companies are actively pursuing. Monsanto itself has a whole web page devoted to the technology, which they call RNA interference.

Gurian-Sherman notes that the Chinese study — though requiring confirmation and follow-up research — raises “an initial red flag.” It calls into question “any general statement that [microRNA] technology would be inherently safe,” he adds.

He observes that humans and insects share a surprising amount of DNA material — evolution favors reusing and recycling genes even among creatures as different as insects and humans. If this research bears out, then it’s entirely possible that microRNA meant to target a specific insect gene will also have an effect — possibly unpredictable — in humans. This is especially true because, for technology like this to work as a pesticide, the microRNA must be present in high levels in the plant, which makes it even more likely the genetic material will make it all the way into the human gut.

Gurian-Sherman also pointed out that microRNA techology poses an even greater environmental risk. There are many beneficial insects, such as various beetle species, that are closely related to crop pests and can coexist in the same field. It’s thus hard to imagine being able to find a gene to target in a pest that won’t also hurt their beneficial cousins (though this is unlikely to matter to biotech companies).

So where does this new research leave us? It suggests that, given the possibility of affecting humans and other bystander species, microRNA-based technology would require unimaginably high safety standards. And neither the biotech industry nor federal regulators have really shown an appetite for that kind of rigorous testing. Am I the only one who doesn’t see that changing anytime soon?

UPDATE: Dr. Michael Hansen, Senior Scientist at Consumers Union wrote to me after this post was published with an important point about the significance of the Chinese study. While he agreed that the main implications relate to the possible risk from microRNA-based GM foods, he also felt that this study did make a new and somewhat startling finding regarding how plant genetic material affects humans. As he put it, the study “showed that the miRNA not only survived digestion [in humans] but also was taken up and moved to other parts of the body where a specific impact was noted. The studies you cited — from Seralini’s lab and Malatesta’s lab — only show that GE crops can have an adverse effect on animals.”