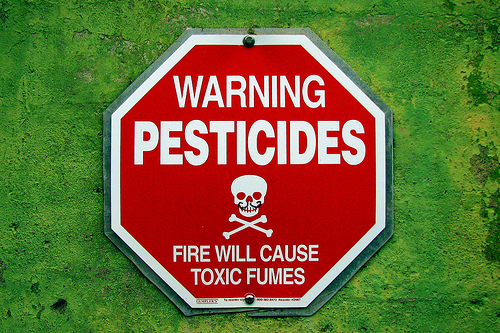

Photo: C.G.P. GreyI recently wrote about a quiet but vicious fight going on in Congress to restrict the EPA’s ability to regulate pesticides. It’s in many ways an obscure bureaucratic turf battle, only this one is about how easy it should be to douse that turf in toxic chemicals.

Photo: C.G.P. GreyI recently wrote about a quiet but vicious fight going on in Congress to restrict the EPA’s ability to regulate pesticides. It’s in many ways an obscure bureaucratic turf battle, only this one is about how easy it should be to douse that turf in toxic chemicals.

It all comes down to two competing visions of how we should use pesticides — either as much or as little as possible. For the most part, the EPA approves a pesticide when a company “lists” the chemical with the agency under the terms of the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA). To get a pesticide listed with the EPA, a company has to submit its own data showing that the pesticide won’t cause undue environmental harm. Once a pesticide is listed, in most cases, farmers can use it as they see fit — with one notable exception.

Under the Clean Water Act, if a farm wants to spray pesticides near a body of water, it needs to get a permit, with the idea being that alternatives to spraying should be explored first. Industry hates this requirement and has made various attempts to get around it, including a successful effort several years ago to get the EPA to exempt any pesticide listed under FIFRA from Clean Water Act permitting requirements.

When the courts stepped in and overturned EPA’s rule, saying the agency had to come up with a permitting system for pesticide spraying near water after all, industry started a round of legislative efforts to stop the EPA’s process. And now, given the anti-regulatory fervor gripping the House and the Democrats’ lack of interest in picking fights, it appears as if industry will succeed.

A bill that would overrule the Clean Water Act permitting requirement easily passed the House earlier this spring and has this week been approved by the Senate Agriculture Committee, the L.A. Times Greenspace blog reports; it may soon pass the full Senate. If it does pass, “companies can do whatever they want” when it comes to spraying pesticides near bodies of water, NRDC staff attorney Mae Wu told the L.A. Times.

Industry will tell you that requiring a permit is duplicative because the pesticide has already been listed as safe with the EPA under FIFRA. But industry has rigged the game: FIFRA is designed to set maximum allowable levels of pesticide use, while the Clean Water Act provisions are designed to minimize pesticide use. Meanwhile, the underlying safety data are all coming from the company seeking to sell the product in the first place — a deeply problematic way to establish appropriate levels of use.

This is, sadly, one of the few senses in which agribusiness can be considered liberal — i.e., in its desire to use deadly chemicals (not to mention in its checkwriting to lobbyists) — and environmentalists, indeed anyone who cares about clean water, can be considered conservative. It would be ironic if it weren’t so toxic.