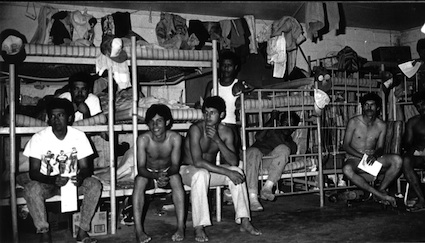

Like a factory in the field, except for the wage protections, benefits, and union. Photo: Vera ChangMost corporations involved in the food business quietly benefit from the invisibility of U.S. farmworkers. Bon Appetit Management Co., a U.S. subsidiary of the U.K.-based, transnational catering giant Compass Group, has done something odd: It has partnered with the nation’s leading farm worker’s union, the United Farm Workers of America, to produce a blunt, important report on the conditions of farm labor in the United States [PDF].

Like a factory in the field, except for the wage protections, benefits, and union. Photo: Vera ChangMost corporations involved in the food business quietly benefit from the invisibility of U.S. farmworkers. Bon Appetit Management Co., a U.S. subsidiary of the U.K.-based, transnational catering giant Compass Group, has done something odd: It has partnered with the nation’s leading farm worker’s union, the United Farm Workers of America, to produce a blunt, important report on the conditions of farm labor in the United States [PDF].

How weird is that? Well, most of Bon Appetit’s peers in the food industry prefer not to examine conditions in farm fields. They bargain hard for the lowest price they can get for raw materials, and their bargaining power only makes things worse for field workers. To survive selling perishable goods to vast firms like McDonald’s and Walmart, farm operators scale up and strive to maximize production while keeping costs as low as possible. One way to slash costs is to pay as little as possible for labor.

Thus we get situations like the one in Immokalee, Fla., where a handful of growers control a vast winter-tomato production machine, and are in turn dominated by a few big supermarket and fast-food buyers. The Immokalee situation metastasized into a scenario where a large group of migrant laborers were working for sub-poverty wages and living in housing with prices befitting Manhattan and amenities befitting Apartheid-era Soweto. When those conditions are “normal,” no one should be surprised that outright slavery crops up. The Coalition of Immokalee Workers (CIW) had the insight that these conditions couldn’t begin to change until they challenged corporate buyers to pay more for tomatoes. Their penny-per-pound campaign forced McDonald’s, Burger King, and Taco Bell to pay more for tomatoes so that farmworkers could get a raise.

Those companies resisted the CIW effort bitterly, and only gave in under public boycott pressure. Other corporations continue to hold out, including the biggest tomato buyer of all, Walmart. Paying a penny more per pound for tomatoes would betray a business model built precisely on pinching every penny and squeezing workers.

Few areas in the nation have as strong and organized a farmworker presence as Immokalee. The 1.4 million people who labor on farms nationwide mostly work in similar conditions. With this report, Bon Appetit Management, which signed the penny-per-pound agreement in 2009, is shining a bright light on the entire system. The Bon Apettit/UFW researchers surveyed the available information — itself scandalously sketchy — about farm-labor conditions and the laws that govern them and put it all in one place.

You can’t read it without drawing the conclusion that the people who harvest the vast bulk of the food in this country tend to live in poverty, are exposed routinely to dangerous chemicals, and operate with little protection from unions or government regulators.

To wit:

Between 2005 and 2009, about a third of farmworkers earned less than $7.25/hour and only a quarter of all farmworkers reported working more than nine months in the previous year. One-quarter of all farmworkers had family incomes below the federal poverty line.

Just 7 percent of U.S. farmworkers make $13.25 per hour or more, the report states.

Those are startling facts when you cross-reference them with this New York Times piece on recent research examining what it takes to attain “economic stability” in the United States. Get this:

According to the report, a single worker needs an income of $30,012 a year — or just above $14 an hour — to cover basic expenses and save for retirement and emergencies. That is close to three times the 2010 national poverty level of $10,830 for a single person, and nearly twice the federal minimum wage of $7.25 an hour.

As an economically stable life is out of reach for most single farmworkers, those with families are in even more of a bind:

A single worker with two young children needs an annual income of $57,756, or just over $27 an hour, to attain economic stability, and a family with two working parents and two young children needs to earn $67,920 a year, or about $16 an hour per worker.

The pauperization of farm labor cannot be surprising, given that U.S. labor laws — including the National Labor Relations Act and the Fair Labor Standards Act — exempt farmworkers from protections. Given all the furor surrounding the public-union crackdown in Wisconsin, the report gives us occasion to remember that the right to collective bargaining is explicitly denied farmworkers:

Consequently, under federal law, a farmworker may be fired for joining a labor union, and farm labor unions have no legal recourse to compel a company or agricultural employer to negotiate employment terms. The majority of state laws do not include any collective bargaining provisions for farmworkers. A mere 1 percent of farmworkers interviewed reported that they worked under a union contract.

The entire report is well worth reading, as students of farm labor will likely be doing for a while. Put it beside another recent report — Southern Poverty Law Center’s “Injustice on Our Plates: Immigrant Women in the U.S. Food Industry” (hat tip Jill Richardson) — and you get a rather grim picture of life among the people who feed us.

Typical farmworker housing in California.Photo: United Farm WorkersOur food system — despite the pummeling it has taken in recent years from the likes of Michael Pollan, Eric Schlosser, Marion Nestle, and blogs like this one — remains celebrated for its efficiency, its ability to crank out massive calories at low cost. Some would like to see the entire global food system modelled on it. Just today, the influential blogger Adam Ozimek and I were butting heads on Twitter over the topic of cheap food. Ozimek heralded Walmart as a model of efficiency within the food system. If people are struggling to get by at current U.S. median wages, he argued, the answer is to make stuff cheaper. And food, he suggested, was an area of the economy where prices could fall more.

Typical farmworker housing in California.Photo: United Farm WorkersOur food system — despite the pummeling it has taken in recent years from the likes of Michael Pollan, Eric Schlosser, Marion Nestle, and blogs like this one — remains celebrated for its efficiency, its ability to crank out massive calories at low cost. Some would like to see the entire global food system modelled on it. Just today, the influential blogger Adam Ozimek and I were butting heads on Twitter over the topic of cheap food. Ozimek heralded Walmart as a model of efficiency within the food system. If people are struggling to get by at current U.S. median wages, he argued, the answer is to make stuff cheaper. And food, he suggested, was an area of the economy where prices could fall more.

I don’t want to delve too deep into that whole argument now, except to say that Ozimek’s line of thought raises a paradox: the way to make life more livable for low-income people like farmworkers is to put more pressure on food prices — and that means yet more downward pressure on farmworker wages and working conditions. Surely we can think of more creative and less cruel ways of running our economy.

Bon Appetit deserves credit for working with UFW and using its power and profit to shine a light on the situation — thus making it less easy for people like Ozimek to ignore the bitter paradoxes that underpin the easy bounty that sustains them.