Last summer, after a series of devastating wildfires, the Oregon state legislature passed a sweeping bipartisan bill to protect against future blazes. The law unlocked money to develop new building codes in vulnerable areas and help residents who wanted to fireproof their homes. It reached the governor’s desk with support from Portland-area Democrats and rural Republicans alike.

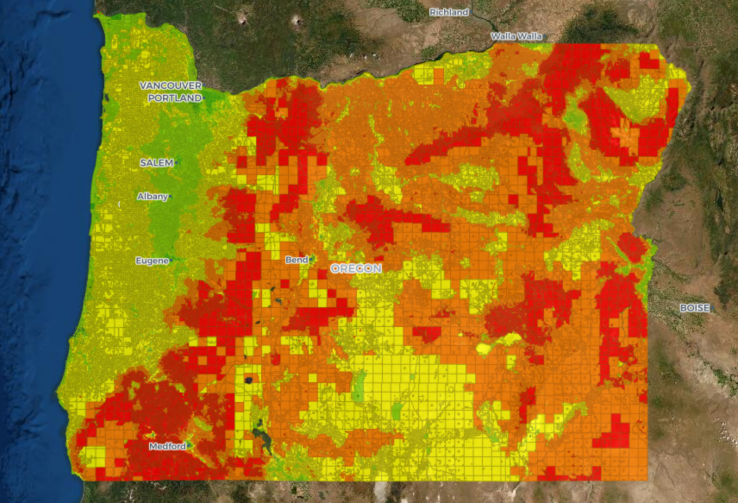

Before state officials could implement the new regulations, though, they needed to figure out which areas faced the greatest fire danger. For this reason, the bill required the state forestry department to create a comprehensive wildfire risk map within a year, assigning a risk score to every household in the state. The forestry department finished the map right on time in June. It then mailed a letter to every homeowner who was in a high-risk zone, alerting them that new regulations would be coming soon.

This seemingly anodyne mapping measure produced a frenzy of backlash from every corner of the state. Hundreds of residents showed up at public meetings to berate state officials for designating their homes high risk, and hundreds more wrote in to contest their risk status. Many argued that the state was going to make their insurance more expensive and their property less valuable.

The same Republican lawmakers who had supported the wildfire bill then pounced on the map as an example of state overreach. In early August, the state caved and withdrew the map, vowing to spend another year gathering feedback before releasing a final version. In a tight race for state governor that will be decided next week, the Democratic candidate has distanced herself from the old version of the risk assessment, saying the revision “must address concerns from property owners.”

The fracas over the wildfire map serves as a warning to other states and cities that are trying to adapt to climate change. When the government tries to impose new restrictions on homeowners in vulnerable areas — or even tries to inform them about the risks they face — the homeowners may fight back. Many residents who protested the map were misinformed about how the new regulations work, but there was a grain of truth to their complaints: By publicizing their high-risk status, the state may make their homes less valuable and harder to sell. Like many other adaptation efforts around the country, Oregon’s wildfire program may face the greatest pushback from the very people it’s trying to help.

Kim Mead, who lives on a ranch in mountainous Wasco County, was one of the homeowners who fell in the state’s high-risk category.

“They sent us a letter and it showed that we were in the extreme level,” she told Grist. “We called the number to appeal, but nobody answered. There was not a chance to give input.”

Mead has cleared trees and vegetation on her property and surrounded her house with water and gravel to prevent fires from reaching it. Even though two wildfires have scorched her grazing fields in just the last three years, she feels confident that her house itself is safe.

A few weeks after the letters went out, the state held a virtual meeting to discuss the map. Around 900 residents called in, filling the two-hour video session with a litany of complaints.

“I don’t know what kind of science you used,” said one resident, “but it doesn’t make sense to me.” Another called the measure a “complete fraud, unmistakably a fraud.… I’m having a hard time getting out everything I have to say, because I’m angry.” The state had planned to host an in-person meeting, but it changed to a virtual format after receiving a phone message with a violent threat.

It wasn’t long before all these residents got organized. Nicole Chaisson, a hay farmer who lives outside of a riverside town called The Dalles, started collecting stories of people who’d prepared their property for wildfires but still found themselves designated as high risk. She started working with homeowners in other parts of the state to organize letter-writing campaigns to local legislators. (Chaisson has been active in politics before: In 2020 she founded a Facebook group that spread a baseless theory about the state changing voters’ party affiliation without their consent.)

“A lot of people were just, you know, shocked,” Chaisson told Grist. “The big thing that people think of is, you know, the worst-case scenario, which is losing your insurance and having your property taken away.” Pretty soon, the residents had caught the attention of their elected representatives, many of whom had supported the omnibus fire bill the previous year. After hearing the complaints, some of them reversed their positions.

Mark Owens, a Republican state legislator who represents the rural eastern part of the state, said he’s worried about how the map will affect home values. Like Chaisson, he worries that insurance costs could go up, and that home values might drop as a result. Some homeowners in risky areas might even have trouble selling their properties, he speculated.

“You’ve possibly just devalued … that property asset by inaccurately reporting the fire danger,” he told Grist. Owens voted for the wildfire bill that ordered the map, saying it would help protect his fire-prone constituents, but since it debuted he’s been focused on rolling it back — also in an attempt to protect his fire-prone constituents, or at least their equity.

Some of these concerns are unfounded. Residents like Mead, who have already hardened their homes against fire, won’t have to do anything once the state debuts the new regulations, since they’ll already be in compliance. As for insurance, the state insists that its map isn’t causing insurers to raise rates. For one thing, most insurance companies have their own algorithms for evaluating risk, and therefore don’t need the state’s.

“The statewide wildfire risk map is a representation of risk that already exists — it doesn’t create the risk,” said Derek Gasperini, a spokesperson for the Oregon Department of Forestry who led the state’s mapping work. He says that insurers make their own decisions about raising prices and offering coverage. When it comes to home values, though, the map’s possible effects are harder to predict. Studies have shown that informing buyers about flood risk can reduce home sale prices or drive customers away, but it’s unclear whether that trend holds when it comes to fire.

“We don’t have a way to mitigate that concern or a response to concerns about home value,” said Gasperini. “That is subjective.”

Even so, the state is far from alone in its effort to map household fire risk. Utilities and real estate companies have plowed millions of dollars into efforts to predict wildfires, developing detailed datasets and algorithms. Earlier this year, the nonprofit First Street Foundation published a national map of fire risk, allowing anyone to search fire risk for any address. If home prices start to fall in the Oregon map’s extreme zones, the map won’t be the only reason why — or even the biggest.

Still, the state’s map generated a special kind of backlash from rural Oregonians, who seemed to blame the state far more than they blamed the insurers or the housing market. Owens, the Republican legislator, says that’s not because of the map itself, but because of the political dynamics behind the adaptation effort. When a liberal administration tells conservative voters what they need to do on their properties, he said, there’s always going to be backlash. (Oregon’s current governor is Democrat Kate Brown, and Democrats hold majorities in both chambers of the legislature.)

“If they haven’t done great outreach with the community and sat down with them, they’re gonna cause us to go political again,” Owens said. “The only way we can get them to slow down is through the public process of being loud, and that doesn’t make good policy.”