February marked the one-year anniversary of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, 12 months of humanitarian, political, and economic crises. Tens of thousands of lives have been lost, millions of people have been displaced, and while the Ukrainian military surprised the world by holding its own and reclaiming half the land captured by Russia this year, the fighting has no clear end in sight.

The conflict also put the global oil trade in the spotlight. From the beginning, some argued that spiking gas prices in the absence of Russian fuel supplies would spur clean energy planning in Europe and elsewhere. But a year out, it has become clear that the war resulted in essentially a doubling down on dirty fuel, at least in the short term. European subsidies for fossil fuels rose higher than ever and carbon emissions reached a global peak as countries scrambled for coal, oil, and gas. Nations that couldn’t afford natural gas turned to burning more coal, and U.S. President Joe Biden called for more domestic fossil fuel production. Meanwhile, Shell, Exxon, and BP reported record profits.

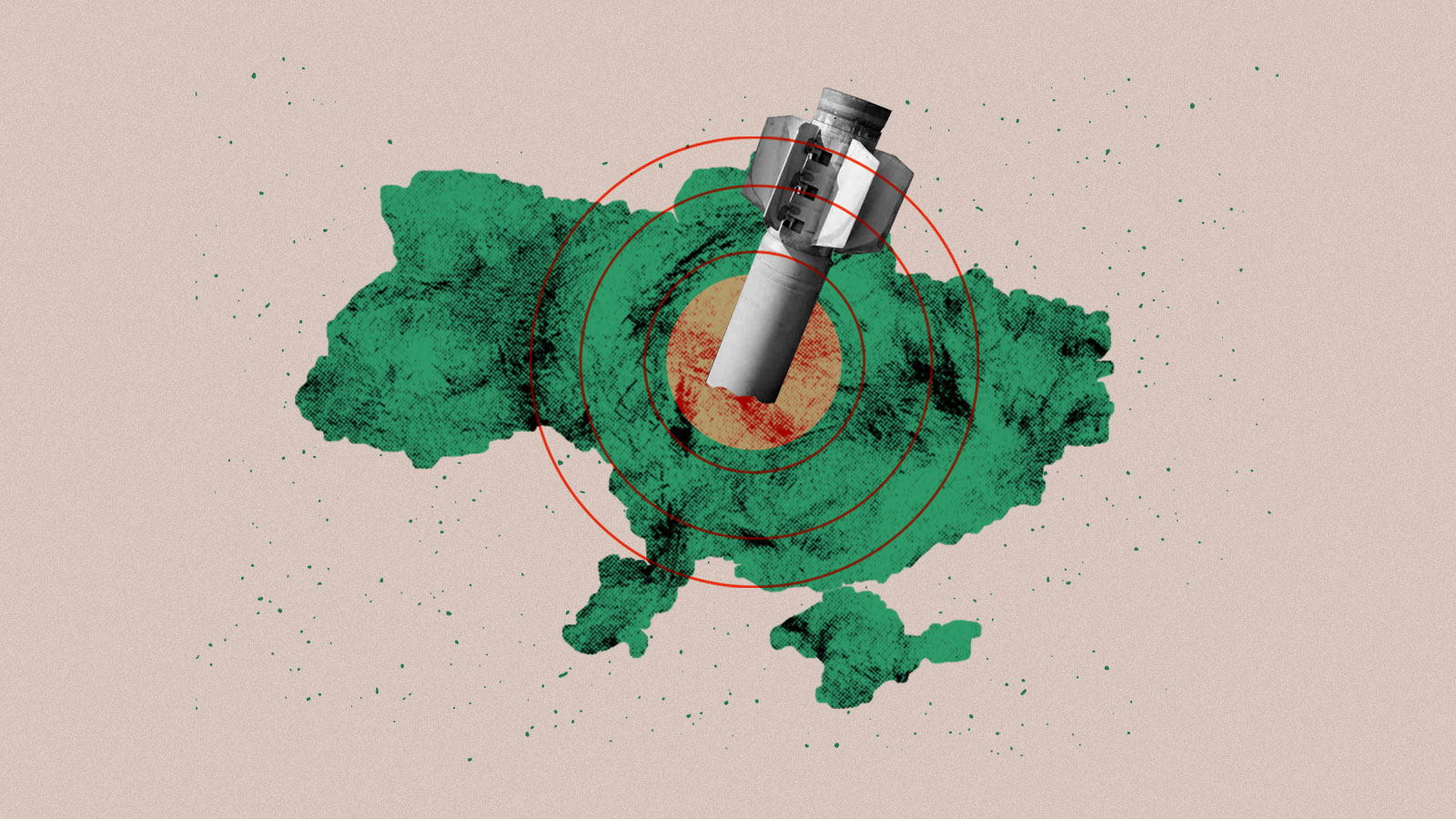

Largely ignored, however, at least in many international circles, has been the war’s massive environmental impact on Ukraine itself. A year out, the extent of these damages are becoming clear. In its campaign, Russia has targeted electric grids, oil refineries, and nuclear plants, and wrought untold damage to ecosystems, soil, and water through the bombing of fields and industrial sites.

“In 2015, we had a fire at an oil facility that was one of the biggest environmental disasters in Ukrainian history,” said Yevheniia Zasiadko, the head of the climate department at Ecoaction, a Ukrainian nonprofit. “Since the Russians invaded, there have been more than 40 such facilities destroyed across Ukraine.”

Attacks on oil depots caused some of the tens of thousands of blazes that have burned across Ukraine mostly started by shelling. About a third of the country’s forests have been affected, and over 57,000 acres have completely burned down, according to data from Ukraine’s environment ministry (as reported in the Economist, the ministry’s website was down at publication time). Oil and trees set ablaze are some of the main contributors to the 46.2 million tons of carbon dioxide, or CO2, released into the atmosphere since Russia’s invasion. The ministry says air pollution has been one of the war’s most costly environmental impacts.

Ecoaction has been tracking the environmental damage since last February, drawing information from media reports and local government announcements and publishing updated findings online every two weeks. Greenpeace joined the effort to provide satellite verification and mapping. So far the team has documented 863 instances of degradation, including widespread forest fires, destroyed terrestrial and marine ecosystems, burst pipelines filling wetlands with oil, sunken ships in the Black Sea, chemical plant waste spilling into rivers, and radioactive releases from nuclear plants. “A huge territory is still occupied so we don’t even know what is happening there,” said Zasiadko. Much of the liberated territory of Ukraine is full of explosive mines, which poses a challenge for mapping and ground-truthing.

“Ukraine is an industrial country and we have a lot of chemical and heavy metal [processing] factories,” said Zasiadko. A big part of that was destroyed, she said, which released toxic materials to flow into waterways and leach into the soil. In the early days of the war, part of a Russian missile hit a livestock waste storage facility near the Ikva river in the Rivne region of western Ukraine and caused a fish die-off in the neighboring region. In another case near the town of Sumy, in northeast Ukraine, people had to stay inside their homes for days after receiving notice of ammonia leaking from a struck power plant.

“Because lots of area was mined [with explosive devices], firefighters cannot do their job, and local scientists cannot go in to monitor the situation.”

Kateryna Polyanska, an ecologist with the Ukrainian environmental nonprofit Environment People Law, has been traveling around the country examining the landscape and taking soil samples from mine craters. “At the beginning I tried to analyze satellite images but that wasn’t enough,” she told Grist. “I understood that I should go to the fields.” Her early lab results have found nickel, zinc, and other heavy metals from shells, bombs, and shrapnel in the soil, as well as chemical contamination and fuel from unexploded missiles. In her travels, she also observed the growing problem of “war waste,” toxic materials from rubble, like asbestos in home ceilings, without any place for proper disposal.

“A lot of these things have a huge risk for human health and lives,” said Polyanska, adding that the attacks and their aftereffects have also impacted animals, like foxes in the forest, dolphins in the Black Sea, and rare ecosystems like the Holy Mountains in the Donetsk province, in the east of Ukraine. Over 30 percent of the country’s natural protected areas have been hit and the environment ministry estimates 600 animal species and 880 plant species are at risk of extinction, as reported in the Guardian.

Another area of particular concern has been nuclear radiation. Last February and March, Russian forces occupied the Chernobyl power station, the site of an infamous 1986 nuclear accident, for five weeks; they dug trenches in the thousand-square-mile radioactive exclusion zone, now effectively a protected area. Studies after they left showed radiation levels three times higher than normal in parts of the Red Forest.

“Because lots of area was mined [meaning scattered with explosive devices], firefighters cannot do their job, and local scientists cannot go in to monitor the situation,” said Denys Tsutsaiev, a Greenpeace campaigner in Kyiv. He added that just after the liberation of the Chernobyl territory, a fire truck drove over a mine and exploded.

Ukraine’s four active nuclear plants from which the country sources half its electricity are also at risk. For the past eleven months, Russian forces have occupied the Zaporizhzhia plant in the south of the country, and damages to surrounding power supply lines raise concerns about reactors overheating. “At the moment there is only one backup line connected to the plant,” said Tsutsaiev. Russians have also drained the nearby Kakhovka reservoir, used for cooling the plant’s reactors and providing water to large populations to the south.

Donbas, the country’s eastern region where much of its industry is concentrated, is also the country’s main coal producing area. It has long been a site of conflict, proclaimed partially as an independent territory by pro-Russian separatists in 2014 and currently under Russian occupation. Between 2015 and 2021, international monitoring showed that over 30 coal mines had been flooded in the region, polluting groundwater and surface water with metals, sulfates, and mineral salts. Since the beginning of full-scale invasion, 10 more have been flooded, though it’s possible that the actual number is higher.

“Usually when Russia occupies a territory they cut off electricity,” said Zasiadko. “That means the pipelines aren’t taking out groundwater, and the mines flood.”

While much of Ukraine’s power grid miraculously remains standing, over 213 reported attacks on electric facilities over the last several months have left large parts of the country without power, limiting drinking water treatment and compromising human health.

With war still raging, Zasiadko says it has been hard to get Ukrainian officials and international allies to pay attention to reconstruction in liberated areas. Harder still is drawing resources for environmental restoration.

“Ukrainian authorities are speaking about ecocide but there isn’t much action on ‘what are we going to do with the pollutants?’,” said Zasiadko. “There is mostly discussion about rebuilding infrastructure and roads.” In July, at the Ukraine Recovery Conference in Lugano, Switzerland, Ukrainian authorities presented their first reconstruction plan to a large group of international leaders and finance institutions; environmental groups objected to it on the grounds that it consisted mostly of construction projects “without a systematic approach to nature conservation.”

Zasiadko says the priority, when it comes to the environment, needs to be testing, monitoring, and pollution clean-up. Ukraine’s economy is 40 percent agriculture, she said, and it’s already coming back in the reclaimed areas. “At the moment the soil is not always de-mined and there have been many examples of explosions on farmlands.” She is concerned that people are growing food in polluted soil. Soil cleanup is a long endeavor, specific to the site and the contaminant. And de-mining could take 10 years. “In the future, we will need special divers who can go in and clean the rivers from explosive materials and mines,” said Polyanska.

Ukraine’s environment ministry, for its part, is keeping an extensive record of the environmental damage and evaluating the cost with the goal of demanding compensation from Russia. The ministry’s most recent findings report that almost a third of the country remains hazardous, 160 nature reserves are under threat of destruction, and the total cost of environmental damage is over $50 billion. While Tsutsaiev appreciates the efforts to document the damage, he says the government and partners should also be seeking other funding and making a plan for how restoration is going to occur.

Ukraine was in the midst of a “just transition” pilot program to help coal workers find new clean energy jobs in nine cities in the eastern coal mining regions when the war broke out. That project has been put on hold. Tsutsaiev hopes reconstruction can be used as an opportunity to rebuild with climate change in mind.

“Greening the reconstruction means empowering local municipalities not to use all the old technologies but to think about energy independence and energy security,” said Tsutsaiev. He cited the example of a hospital close to Kyiv that was damaged in the first days of the war. Greenpeace helped with the installation of a heat pump and solar panels during reconstruction. “Now, when there is no electricity in the area, the hospital continues to receive power,” he said.