This article is part of Ask Umbra’s guide on How to Dress for the Planet.

To attempt to buy “sustainable” clothing in 2022 is to face a carnival’s worth of smoke and mirrors — that is, if you’re buying new. Any consumer seeking to verify the various promises of “recycled fabric,” “climate-positive cotton,” or “non-toxic dyes” will find themselves stymied, because there’s perilous little in the way of enforceable standards for environmental responsibility in the fashion industry. And even if any of these claims are true, there is a momentous quantity of research required to find out if they actually matter.

The green credentials of used clothes, on the other hand, are much easier to verify. Sticking to the mantra “buy little new, plenty used, wear it a lot, and care for it well” is the most reliable way we have to reduce our fashion footprints. But the thing about textiles is that they tend to show their age over time. They rip, they stain, they stretch. If you want to preserve the life of anything old, you will have to mend it at some point.

But modern mending doesn’t attempt to hide itself — to the contrary. Clothes are starting to wear their scars proudly, if you look for them. But for many people, taking a needle and thread to cloth has become something of a lost art. A survey by Colorado State University showed that 55 percent of participants had never mended their clothes, and only 20 percent felt confident in their mending skills.

I relate to that latter 20 percent. In theory, I am able to sew. I can thread a needle and take care of a detached button. But the prospect of executing something that requires a degree of real concentration or skill — say, a straight row of stitches or a hem repair — ignites within me a fiery frustration at the many mundanities of life. It’s akin to the feeling that comes when asked to attend a virtual birthday party.

Meanwhile, my mother approaches a sewing project with the type of zeal that I imagine Lady Gaga must experience as she prepares to take a stage. That is because she is, like Ms. Germanotta, a 5-foot-1 master of her craft; my mother’s sewing skills are, to me, nothing short of awe-inspiring. I have watched her patch a pair of pants in the time it takes me to drink a cup of coffee. She has repaired the linings of the most finicky vintage coats and turned scraps of cashmere sweaters into throw blankets for each of her children.

However, my admiration for her abilities has unfortunately enabled my own mending reticence. Despite the fact that I am an otherwise independent, self-sufficient woman in my 30s, if I ever sustain so much as a fingernail-sized rip in a pair of leggings, I immediately call Mom.

But in the last couple of years, I noticed a shift in her work. The mending projects stopped trying to conceal whatever damage had been sustained in the material. Her patches became brighter and louder — enhancing the garment they were restoring. A moth-eaten sweater was returned with a spray of jewel-tone darning triangles; the disintegrating rear of my denim cutoffs came back as a cheerful patchwork of old jean scraps.

I asked my mom how this shift happened, and it actually is almost entirely the result of my older sister Lena’s existence. When my parents had her, they were young and didn’t have a lot of money, and my mom would buy her baby clothes at thrift stores. Often the clothes would need to be mended — so she’d appliqué some cute patches in a decorative pattern.

And many years later, the tables had turned somewhat, and my sister found herself with a drawer full of cashmere sweaters that had been eaten by moths. She brought them to my mother, not wanting to throw them away but not knowing what else to do with them. Mom cut them into pieces to sew into mittens, blankets, and scarves; and then started to use the scraps from those projects to patch other sweaters in the same decorative fashion as she’d used for Lena’s baby clothes.

“If you have something not quite perfect, you can make it interesting and functional at the same time,” she told me. “And if you’re going to do that, you might as well make it cute!”

The embracing of “not quite perfect” is more of a political statement for the Mending Bloc, a sewing cooperative in Portland, Oregon, that mends clothes for their community and distributes mending kits. The members, who use pseudonyms even among themselves, see the practice as a way to resist capitalism’s wide-reaching, damaging hand. If you are able to mend your clothes, you rely less on buying lots of new things from corporations that profit from selling them to you. With the growth of ever-cheaper clothing, more and more consumers have seen it as less effort to simply go out and replace a damaged garment than take the time to fix it.

“I just honestly think people are tired and overworked and simply don’t have a lot of time to learn a new skill, or develop a passion for it, let alone have the energy for it,” said mudpuppie, a pseudonym-using member of the Mending Bloc. They added that a person is unlikely to start sewing if they see it as another burden on an already onerous to-do list (ahem, guilty). It would have to be enjoyable, and “most people are too exhausted to discover if something like sewing brings them joy.”

Rebecca Harrison, who started her Pittsburgh mending and tailoring business Old Flame Mending in 2019 with her friend Tia Tummillo, offered another reason for why sewing and patching have disappeared from many people’s skill sets over time: “I think that the connection with the objects and things you use every day isn’t as strong as it used to be.” This is, of course, another product of the cheap fashion industry: If the barriers to keeping the clothes you have intact are higher than buying new ones, well, why would you go to the trouble?

Naturally, it makes no financial sense to ditch long-wearing investments like down jackets or leather boots at the first sign of a scuff or pulled thread. But there are other reasons to save a garment from the trash heap: Everyone has that one perfect pair of jeans or their grandfather’s old flannel whose emotional value thwarts all economic logic. Harrison first started thinking about the business she has today when she worked for a tailoring shop that would reject all kinds of garments that they deemed “not worth fixing” because they simply couldn’t be perfectly restored to mint-looking condition.

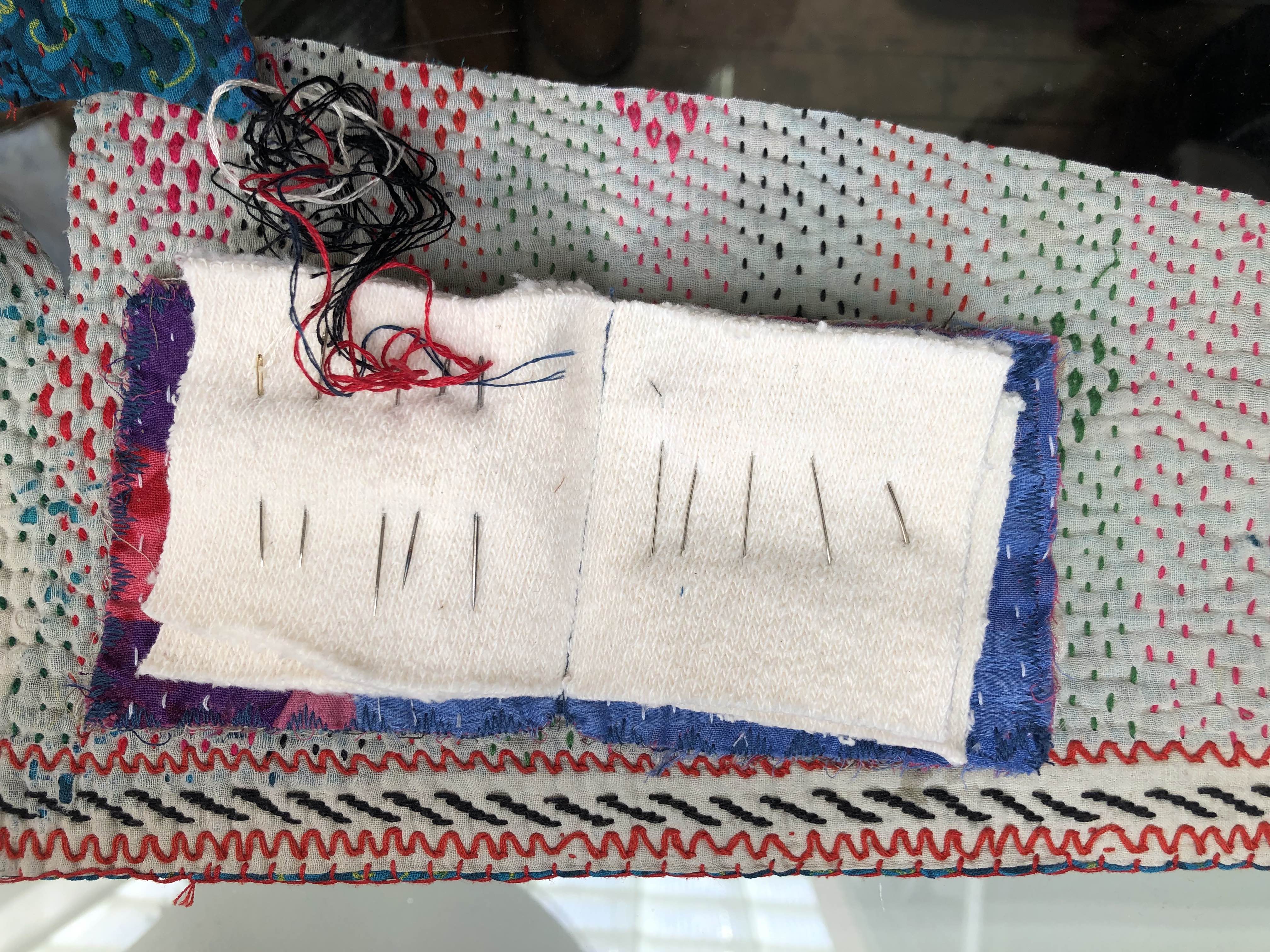

That’s where the visible mending comes in — the colorful scars, if you will. This is nothing new outside of Western culture — the Japanese embroidery boro and sashiko, or the Indian sari-repurposing method of kantha, go back hundreds of years. But as many countries industrialized, it became less necessary to preserve clothing in thoughtful and beautiful ways; garments became both simpler and cheaper to create via the innovation of manufacturing. By the time we rolled into this tortured century, the practice of decorative mending had largely moved more into the sphere of art than craft, such as the work of British textile artist Celia Pym.

And then, at some point in the past decade, little patches of embroidery and appliqué began to pop up here and there in commercially sold clothing. In 2017, a sewist at the Eileen Fisher Renew warehouse in the industrial district of Seattle showed me some whimsical stitching she’d done to cover a small tear in a blouse. (The Renew arm of the Eileen Fisher brand takes back lightly worn clothing to wash, restore, and resell at a discounted price.) The material of the blouse was too delicate to be mended invisibly, she explained, so if the stitches are going to be obvious, why not make them interesting to look at?

The same sort of embellishment can be seen in the work of smaller designers, too. Rona Chang has been sewing one-of-a-kind jackets out of old quilts and other textiles since 2018 under her independent brand Otto Finn. Because she works with older fabrics, many of her pieces are obviously — and intentionally so — patched or embroidered. “Part of my practice is to make the most out of something that is already in existence,” she said, “and to be able to just patch it up a little bit so we can keep using it, and it’ll be not the same as new but good as new. It prolongs the life of something.”

Visible mending is an obvious (in more ways than one) balm for a planet overburdened by a shocking weight of exploitatively manufactured clothes, but it’s a little harder to unravel exactly what its resurgence signals for the fashion industry’s sustainable bona fides. Encouragingly, it’s almost the polar opposite of the artificially “distressed” trend that has surged in and out of fashion from the 1980s all the way up to today. The false wear and tear of pre-ripped jeans and paint-splattered T-shirts at several hundred dollars a pop is the sartorial equivalent of zombie makeup painted on an actress by a special effects team. But when someone puts in the effort to heal the authentic wounds of cloth, they’re demonstrating that they care enough about the lifespan of something man-made to make sure it doesn’t collapse in tatters off someone else’s body.

But just like carefully saving your food scraps to compost, biking through a bitter winter afternoon in lieu of driving, or making sure every light is turned out when you leave a room, taking the time to patch up a tiny hole brings to mind the familiar refrain: Why am I bothering to make an individual change when it’s really an entire industry that has to change its ways? And climate advocates say it is crucial that retailers and designers use these creative methods to keep textiles in circulation as long as possible.

“Even the most sustainable designers are kind of running into this question of, ‘What is conscious consumption under capitalism?’” said Rebecca Harrison. “What does this mean to be putting new stuff out into the world, when there’s already so much here?”

Emissions aside, reviving the people’s art of the patch is a good way to do battle with consumerist culture. Pocket, another member of the Mending Bloc, suggests the main barrier to mending “is not a lack of interest or will, but financial limitations and knowledge or skill barriers.”

There’s certainly a generational element to how sewing has traditionally been taught; almost everyone I interviewed learned it, in some capacity, from their mother or grandmother. (My own mom certainly tried to teach me, to no avail.) But for those who missed that boat, or who never had the opportunity, there is a far less sentimental way to learn: the world of social media.

Harrison explains that “arts and craft in general has become more democratized with the rise of social media.” Especially over the past interminable years of the pandemic, you have millions of people trying to learn new skills at home and eager to show off the fruits of their labor. It’s a proven recipe for a movement.

Multiple members of the Mending Bloc described how they’d honed their own sewing practice by watching YouTube and Instagram tutorials. But they also emphasized the idea that you shouldn’t have to be responsible for exhaustively maintaining your wardrobe entirely on your own.

“Maybe you’re great at mending clothing seams, but can’t figure out how to darn socks,” explained Rita, “and that’s OK, because if you have a community of makers and menders, there’s bound to be someone there who can help.”

As for me, I do not think I am unique when I tell you that there is a fantasy version of my life where I do all sorts of good-for-the-Earth, homestead-y things. I grow my own vegetables, I make preserves, I mend all my own clothes and even sew ones for myself out of vintage textiles — the kind of simple yet flattering linen smocks that you imagine really fulfilled people wearing. But I also know that I get too easily frustrated when new skills do not come naturally to me, and perhaps that’s the real lesson here: that the more climate-compatible versions of our lives require an element of patience.

I consider every mender I interviewed for this story to be an expert, a person in possession of awe-inspiring prowess and dexterity. And yet, each one emphasized how they are constantly learning and trying out new methods and techniques to tackle particularly finicky projects. So in addition to wearing our imperfections with pride, perhaps what we really need to abandon is the expectation of an “easy fix” for any problem, be it as simple as a hole in a sweater’s elbow or as complex as the global clothing industry.