This story was published in partnership with Mongabay.

As nearly 200 countries struggle to negotiate a new plan for nature conservation at the United Nations’ Biodiversity Conference in Montreal, Canada, known as COP15, Indigenous-led guardian programs in Canada may offer tangible successes in protecting crucial lands and waterways.

Representatives from around the world are aiming to hammer out a new agreement on a number of issues, a critical one being the preservation of at least 30 percent of the planet’s land and water resources by 2030, a plan known as “30×30”, to create protected areas and halt ecosystem and biodiversity loss.

Talks are currently moving slowly and Indigenous leaders say the conservation target must include Indigenous rights and inclusion for a successful final agreement, pointing to serious human rights violations and land expropriations as one potential outcome of an agreement without Indigenous input. The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Tanzania, Kenya, Nepal and India have become flashpoint cases of people displaced to create protected areas, with large conservation NGOs such as the World Wildlife Fund and Wildlife Conservation Society linked to human rights abuses including group rape and killings.

WWF has recently distanced itself from rights abuses at a U.S. congressional hearing and WCS denies allegations brought against the organization

Many scientists, and some governments, say the best way to meet the 30×30 goal involves working with Indigenous communities to expand formal protected areas on their lands. Recommendations include the recognition of ownership, and management or governing rights to traditional lands, which often coincide with better conservation outcomes. According to estimates by the ICCA Consortium, an equity in conservation organization, 30 percent of land on Earth is already conserved if Indigenous lands are taken into account, and Indigenous communities conserve an estimated 80 percent of Earth’s remaining biodiversity.

In Canada, First Nations guardian programs may offer one example of how governments can work with Indigenous peoples to reach global goals, Indigenous delegates at COP say.

“This COP is all about halting and reversing biodiversity loss,” said Valérie Courtois of the Innu community of Mashteutiatsh and director of the Indigenous Leadership Initiative. “The best way to do that is by enabling Indigenous leadership.”

Courtois points to the Edéhzhíe Dehcho Protected Area and National Wildlife Area, a conservation zone covering 14,200 square kilometers (about 3.5 million acres) in Canada’s Northwest Territories, an area more than fifteen times larger than New York City. With wetlands storing climate-changing carbon dioxide, plenty of freshwater fish, and rich boreal forests, “the protected area on a northern plateau has long been an essential for local Indigenous culture and food security,” said Courtois. Designated a National Wildlife Area in 2022, it’s home to a diverse mix of northern wildlife, including woodland caribou, peregrine falcons, wood bison, wolverines and rusty blackbirds, according to Canadian government data. It is managed by local Dehcho and Tłichô Dene Indigenous communities and government officials say it offers an effective model for conservation.

Under the terms of the deal between the Canadian government and local Indigenous communities, the lands and waters of the area are permanently protected by federal legislation and safeguarded from any future oil, gas or mineral extraction.

As part of the area’s management, local community members – or guardians – are tasked with protecting the land, providing frontline eyes and ears monitoring ecosystem changes. This can include working with outside scientists on tracking animal populations or medicinal plants, negotiating with industrial interests nearby, or liaising with government officials on water management. “There is no typical day as a guardian,” Courtois said.

The guardians’ success in protecting species and water resources is part of a global trend, campaigners said, with territories controlled by Indigenous communities showing better conservation outcomes than other lands. Five years ago, there were 30 guardians programs in Canada. There are over 120 today.

Currently, some 370 million Indigenous people manage more than a quarter of the Earth’s land surface, according to a 2022 study published in the journal Nature Sustainability. These territories, where Indigenous communities have land rights, intersect with about 40% of the world’s protected areas and at least 36% of intact forest landscapes, providing data to campaigners who argue expanding Indigenous protected areas is among the most effective strategies for improving conservation.

“The 30×30 target is the world catching up to Indigenous ambitions,” Courtois said. “We tend to look at landscapes as what needs to stay rather than ‘what can I take.’”

But some delegates say the plan doesn’t go far enough, pointing to research published earlier this year in the journal Science which found that 64 million square km (about 15 billion acres), or about 44% of Earth’s land area, needs to be protected in order to halt declines in biodiversity. In Latin America, Indigenous leaders are calling to protect 80% of the Amazon.

“Some provinces and jurisdictions may need 60 or 70 percent protection because of the type of environment they have and some not. We can’t just think of protecting 30 percent and we’re good. It’s about protecting the right 30 percent,” said Steven Nitah, former chief of the Łutsël K’é Dene First Nation and chief negotiator for the establishment of Thaidene Nëné or “Land of the Ancestors” Indigenous Protected Area. Nitah says Indigenous communities can provide key knowledge and information in designating which areas should be protected.

However, Indigenous delegates at COP15 remind observers that none of these spatial conservation targets should lead to “fortress conservation”, a practice grounded in the idea that for biodiversity to thrive, humans must be absent.

“Without a serious overhaul, the so-called 30×30 target will devastate the lives of Indigenous Peoples and will be hugely destructive for the livelihoods of other subsistence land-users, while diverting attention away from the real drivers of biodiversity and climate collapse,” a coalition of human rights groups including Amnesty International and The Rainforest Foundation said in a statement ahead of the COP15.

Between 1990 and 2014, more than 250,000 people were evicted from protected areas across 15 countries, according to a report from the Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and the Environment last year.

Amid these differences over conservation targets and approaches, COP15 opened without agreement on draft language that would set up high-level negotiations at the conference.

“Negotiators are wasting time,” said Marco Lambertini, director general of WWF International, during a press conference. There are currently about 400 brackets in the agreement’s text – areas where negotiators still need to agree on. “We see slow progress, squirting around issues and attempts to dilute the text as a cover for continuing business as usual.”

This will be the fifth time COP leaders will meet without a draft ready and are quickly running out of time to clean up the text’s brackets before the arrival of ministers on Thursday. Ministers need to have relatively clean text to discuss and agree on.

“After more than two years of working group negotiations and five meetings, what have they done? Did they use their time efficiently in the Geneva, Nairobi and Montreal negotiations?” Hindou Oumarou Ibrahim, President, Association for Indigenous Women and Peoples of Chad, asked in a press conference. “Or did they use their time vacationing from one country to the next?”

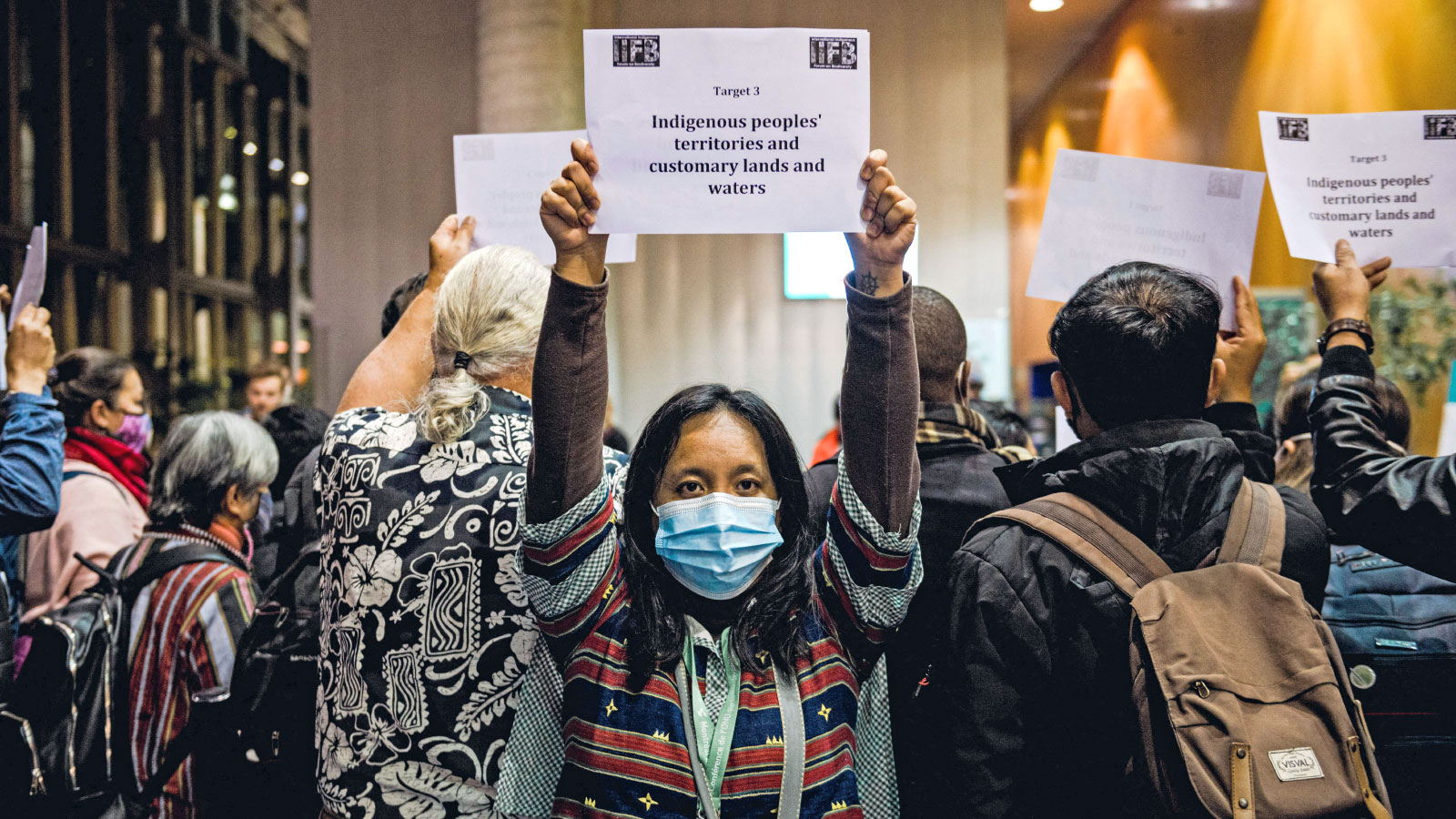

At a press conference kicking off the beginning of COP15, Canada’s Environment Minister said Indigenous conservation will be a core topic at COP15 – and the biodiversity framework must be completed with the full partnership of Indigenous peoples. However, during a speech by Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, Indigenous protestors interrupted the proceedings, holding a banner that read “Indigenous genocide = Ecocide. To save biodiversity stop invading our lands” and called Trudeau a “colonizer.”

The following day, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau pledged an additional $800 million CAD ($560 million USD) over seven years to support Indigenous protected areas, with plans to expand the conservation zones by nearly 1 million square kilometers (about 247 million acres), an area larger than Turkey.

That funding pledge follows multiple others over the years. In 2018, the Canadian government committed $118 million to support Indigenous-led conservation initiatives, including guardian programs in the Edéhzhíe Dehcho Protected Area and National Wildlife Area. In 2021, the country pledged another $454 million to support a host of Indigenous-led conservation initiatives, such as conservation on Inuit Owned Lands and Indigenous Partnerships for Species at Risk.

“Our Nations have governed and managed our territories for more than 14,000 years. When we exercise our stewardship authorities and responsibilities, everyone benefits,” Heiltsuk Chief Marilyn Slett, who is also president of Coastal First Nations in British Columbia, said in a statement following Trudeau’s announcement.

Some analysts say elements of the guardian programs – with local communities having land tenure security coupled with usage rights for hunting, fishing and ceremonial purposes, backed by outside financial support for on-the-ground monitoring – could offer a model for other ecologically sensitive areas, such as the Congo Basin.

“First Nation delegates showed us that Canada was able to meet its own area-based conservation goals because it included Indigenous lands and management in conservation,” said Jennifer Tauli-Corpuz, global policy and advocacy leader at Nia Tero, during a conference event. “We are hoping that this can be a model for other countries to emulate.”

Others say what works in northern Canada doesn’t easily translate to other communities or ecosystems and there is no simple model for ensuring conservation and community land rights.

“We would never tell anyone how to behave,” Courtois said. “But we do hope that we serve as a bit of a model and inspiration for efforts of Indigenous communities in asserting their nationhood and rights and titles on their lands.”