For those of us who live our lives with both feet firmly planted on land, it can be difficult to grasp exactly how much and how quickly the oceans are changing. That’s not the case for Tele Aadsen, a fisherman in southeast Alaska for whom the ocean is both a livelihood and a home. Aadsen, 37, grew up in a fishing family in southeast Alaska and now co-captains a fishing boat with her longtime partner, Joel. In between, she’s worked stints on land and at sea, but she always comes back to the water. Being on the ocean, she says, provides an existential calm she has never been able to find on land.

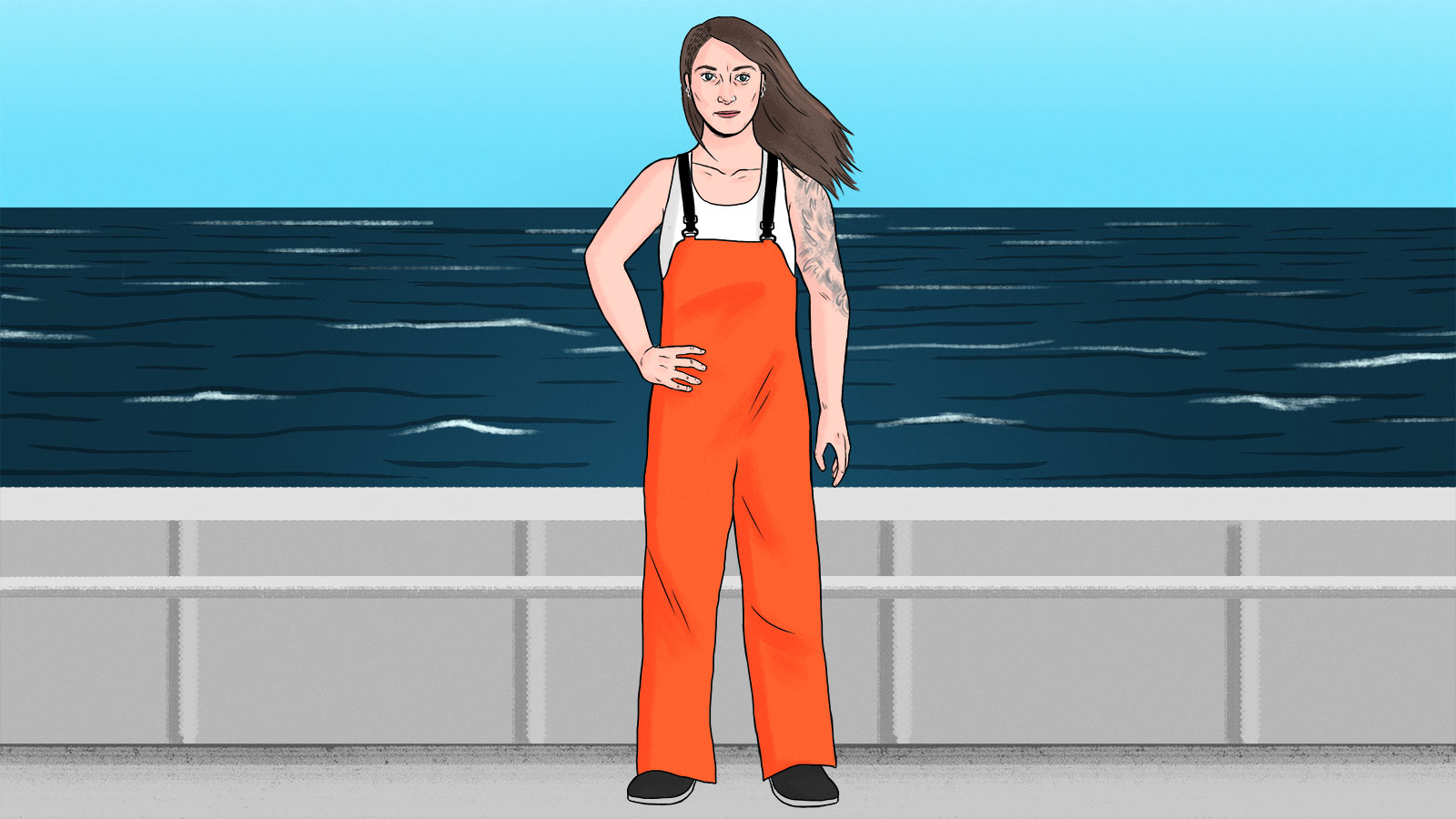

We talked to Aadsen, who trolls for king and coho salmon, about the family business, living as a woman at sea, and what it’s like to be drawn back, again and again, to a changing ocean. Below is an edited and condensed version of the conversation.

Q. What part has the ocean played in your life?

A. The ocean has played a part in my life since birth — and that’s funny since I was born landlocked in Wasilla, Alaska, when no one knew where Wasilla was, back before Sarah Palin. My dad was building a sailboat in the backyard, and I had never seen the ocean. It took him seven years, but then he had a finished sailboat. My parents and I launched from Anchorage and crossed the Gulf of Alaska, landed here in Sitka, and became a fishing family. To go from never having seen the ocean to that being your home — really, it’s been the most constant thing in my life in the 30 years ever since.

Q. What made your dad want to do that?

A. [Laughs.] Warding off depression, I think. He had a real life-threatening injury — a horse had kicked him (he and my mom were veterinarians). His way of dealing with this major life change was to find this great project, to build an ark that would hold our family together, and that was the boat.

Q. And how long did that last?

A. My parents tried fishing off the sailboat for two years, and realized that wasn’t possible. It wasn’t a way that we could make a living as a family. So two years later, they were building another actual fishing boat, and we fished that as a family, another couple years. When my parents split up, I was thirteen. My dad had been really grateful for his years on the water in southeast Alaska, but we had not had success as fishermen. He just didn’t see that it was possible to support a family like that. And my mom disagreed. She took the boat and I was her teenage crew.

[grist-related-series]

That was in 1991. There certainly were women captains and women running boats and fishing back then. She stood out because ours was one of the biggest boats in the fleet, and she was the only one with her teenage daughter as her crew.

She sank everything she had into trying to make a living fishing, and it just didn’t work for us. There were a few bad years and bad low prices, and she had to sell the boat that they had built together.

I crewed on a couple other boats for a few years after that. That was a different experience, because — even though I was still working in the same fleet and the same fishery as I’d grown up in — actually going out to sea with non-family members, I was learning about a side of the fleet that I had been able to pretend didn’t exist: the racism and sexism. And it just made me very bitter, and turned me off to the place that had always been home.

So I left fishing for six years to do social work in Seattle. That was great, but when I got burned out and couldn’t do it anymore, fishing was what I knew to come back to. That was 11 years ago, and I’m still here.

Q. Even after seeing your parents suffer in fishing, what do you think brought you back to it?

A. Being poor didn’t really scare me as a deckhand. The release that I found in the physical labor and the setting here — to have my office be 40 miles offshore, off the coast of southeast Alaska, off these glacier-punctured mountains — that was the first time I felt calm again, after those years.

Q. What effect does it have when you see all your immediate family failing at something?

I wasn’t afraid to keep coming back to this as a deckhand, but I was very afraid of trying to make it on my own, or trying to get a boat myself. And I just never did it. At the same time, I had a lot of self-shame that I was just a deckhand and that I didn’t move on as I saw other young people do, who were willing to risk getting the crappy starter boat just so they could have that freedom of being their own boss.

Q. How have you seen the ocean change?

A. We pay a lot of attention to water temperature. Part of [the technology we use on the boat] monitors the temperature of the water that we’re fishing in, and what salmon like and what they don’t like. They don’t particularly like warmer water. Right now the ocean right out front here at Sitka is 59 degrees — that’s getting on the higher end of what salmon like.

Last September, we were fishing right outside of Sitka, about 5 miles offshore, we saw a school of tuna. Albacore tuna, which is almost unheard of. That’s warming water.

The initial reaction is like, “Oh my god, there’s tuna in Alaska! That’s not right, that’s different.” We don’t know how long this will continue on, or what there is for us to do .

Some folks in the fleet are excellently connected with fish science and politics — they know a lot more than me, to know to be really freaked out about what the future of our industry is. Particularly with ocean acidification working the way up to salmon, through the forage fish on up.

Q. And does that information make its way through the fleet at all?

A. You have a lot of people who elected to be fishermen because they’re very independent folks — and of course there’s no across-the-board commonality in how we interpret what we see, right? Our politics are all so different. You’ll have climate change deniers on one side of the dock, with a Tea Party flag in their rigging, and then you’ll have the rest of us.

The commonality, I think, is this is not an easy way to make a living. It’s labor-intensive and it’s slow, and there’s an element, I think, of love in it for everyone. I think the commonality is: None of us know what we’ll do without this.

Q. Is that something people are talking about?

A. Mmm. [Sigh.] What we talk about is observing how many young families seem to be getting back into trolling right about now, and feeling hopeful about that. Like, “So-and-so just bought a boat and they’ve got their baby on board.” So on one hand, there’s a sense of hope because the bodies are here, because otherwise, we’re a graying fleet in a disappearing industry. But, meanwhile, what’s happening long-term? With the environment and the salmon?

Q. What do you think is behind this wave of young families going into salmon?

A. [There’s] that desire to be more connected to or involved in something real, whether it’s our food or our environment. When we untie the lines and go out this afternoon, it’ll be an hour before my phone stops working and I put it away for the next two weeks. On one hand, that’s kind of this self-indulgent luxury of just stepping away from everything for a little bit. But I think for a lot of us, it’s also our survival — that recharging, and that finding a place, a way of being in the world, that we didn’t find elsewhere.

Q. There’s this romantic ideal of men finding themselves on the ocean in our culture. We all read The Old Man and the Sea in high school English class. Do you feel like there’s anything unique or different about the experience of being a woman on the sea?

A. Some of my female companions here — my mom included — have very staunch opinions that gender doesn’t have anything to do with their experience and they’re tired of talking about it. For me, the experience I have here is colored by gender.

The fact is that this is the tenth year that I’m fishing with my male sweetheart, and we have a really awesome collaboration here, running this boat and selling our own fish. And still, even now, even being happy with that life, there are things I struggle with about being the female partner on board. When am I working with and when am I working for? Is there really only one captain on board? Well, probably, and it’s not me. So gender is a part of my experience, and it comes into my writing a lot. It’s just — I am very much a woman at sea.

Q. There’s this idea that women are inherently more connected with nature and the environment, and that they care about it more than men do. What do you think about that?

A. I think that we don’t do any favors by assuming that one group is more predisposed to romantic things than others. One of the boats that I worked on was with a male captain, and one of the most moving experiences of my life as a deckhand was watching him pull this beautiful big king salmon — a 35-pounder, which is significant — up to the side of the boat and just look at it in the water there, and admire it. And then he audibly said, out loud, “Go find a river,” as he released that fish. That would have been a couple hundred-dollar fish, but it had greater value to him being out in the ocean.