The Beacon Food Forest is giving away dozens of strawberry plants. For free.

It’s a drizzly, chilly, gray Saturday, typical of January in Seattle. In just a few hours, the Seahawks will host the Packers for the NFC Championship. While the rest of the city slugs its first tailgate beer of what will become an epic afternoon of football, 60 or so unpaid farmhands are hard at work. They wheelbarrow wood chips, prune pear trees, and remove invasive species from the hillside urban garden, preparing it for spring. Some are uprooting the profusion of propagating strawberry plants that are taking over pathways and smothering other ground-cover herbage (hence the gratis strawberry plants).

The work party breaks for lunch; people congregate and laugh while a drummer and clarinetist improvise a blues jam. Volunteers sip soup prepared by fellow food foresters, and munch on a local bakery’s donation of unsold bread. Despite the drab weather and humdrum winter work, the vibe is quite lively.

This is kinda how BFF works: Create abundance, share abundance. And have a kick-ass time doing so.

The Beacon Food Forest is a community gathering space overflowing with yummy, organic perennial plants in Seattle’s Beacon Hill neighborhood, about 2.5 miles south of downtown. At about two acres, it’s already the largest edible garden on public land in the U.S. And it’s a wildly prosperous example of the real sharing economy.

Work party jamming at the Beacon Food Forest. Jonathan H. Lee

A food forest is pretty much what it sounds like: “A woodland ecosystem that you can eat,” says Glenn Herlihy, one of the BFF’s founders. A food forest mimics how a wild forest works, but swaps in species that are edible or otherwise useful to humans and other animals. Fruit trees and nut trees cast shade (on sunny days) over berry shrubs, herbs, and veggies, while vines climb up trunks and trellises. Underneath, healthy soil teems with tiny life, storing carbon, water, and other nutrients necessary for plant growth. The BFF leans on permaculture farming, which uses ecological design and a bit of good ol’ human labor to create multi-species gardens that bring forth mountains of flavorful, nourishing grub without fossil fuels or other polluting substances.

By contrast, nearly all of the food we eat is grown in monoculture environments, where every plant is eradicated except for one “crop.” That’s true even of most certified organic products. Instead of natural cycles and diverse species supporting each other, you get “dead” soil that needs constant fertilization, watering, and pest control (i.e. spraying poison on food).

Community food forestry demonstrates a smarter way to grow food locally — which is important, considering that we’re staring at a future of hungry, hungry humans. The BFF is a lush public garden where all of the produce is up for grabs. Instead of dividing the land into small patches for private planting, like most community gardens, volunteers cultivate the whole food forest together and share, well, the fruits of their labor with anyone and everyone. Urban foragers are welcome to reap what the community sows.

“By creating our own local food source, we are taking control of our food system,” writes Herlihy, a gardener and sculptor, in the comments section of Grist’s 2012 story about the Beacon Food Forest.

Lunch around the fire pit, surrounded by potted strawberries. Jonathan H. Lee

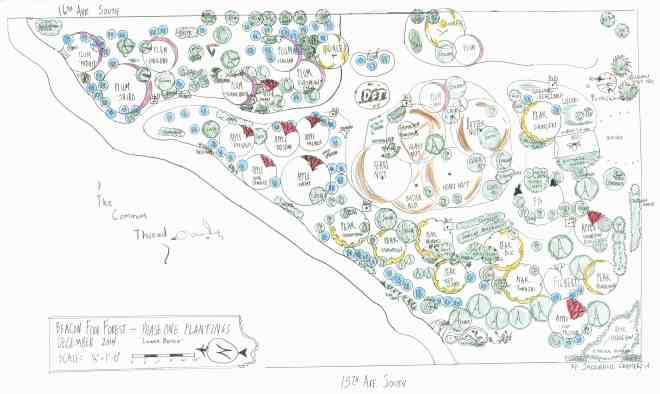

The project began as a big drawing in 2009 — a biodiverse dream of what might be made of a little-used seven-acre field in Seattle’s Jefferson Park. A foursome of locals conceived of the BFF for a permaculture design course they were taking. Herlihy, who was one of those students, sketched it out.

The land, which sits adjacent to a covered reservoir of municipal drinking water, belongs to Seattle Public Utilities. After a few years of bureaucratic haggling and community planning (Crosscut published a compelling history of said haggling and planning), the project was approved by the city in 2012.

Seemingly every rag and zine was writing about this novel use of public space — Forbes, Gawker, Grist. Back then, the big story was how city government was allowing what looked like a loose association of peasants to collectively farm a city park. In assessing the unproven model for community gardening, many questioned adults’ ability to share nicely. NPR’s blog The Salt typified the doubters: “Of course, any ‘free’ food source begs the question of what to do with overzealous pickers.”

Now, the story is that sharing can work. The young food forest already yields more than is gathered. Last fall, BFF volunteers staffed a roadside stand each evening where anyone could bag some of the harvest. Tomatoes, zucchini, green beans, acorn squash, Swiss chard, and other delights were all given freely to whomever wanted some local organic produce.

The community shares the workload and decision-making power, too. BFF emails go out to a list of more than 2,500 volunteers, up to 150 of whom show up for a given work party. An 11-member steering committee, Friends of the Food Forest, creates policies by consensus, while 10 to 15 folks from a rotating cast of dozens attend weekly meetings of various committees that vote on smaller decisions. If you want a say in the BFF, you just show up to be heard and counted.

Really, we shouldn’t be surprised that these folks are so willing to share. A growing body of research in evolutionary science suggests that it is actually our species’ cooperative nature that’s allowed us to win at evolution (and take over the earth, for worse or for worse). Basically, the “selfless gene” — not the selfish gene — helped our ancestors work together to outcompete other chimp-like creatures. Then, as we developed increasingly complex ways of interacting, more and more collaborative traits evolved.

Going forward, the BFF is planning to share the surplus at quarterly community dinners, made mainly from food forest produce. “Not only are we teaching people about permaculture and how to grow food, but we will share healthy, nutritious, yummy ways to enjoy it,” says Kenji Nakagawa, who’s been helping out at work parties and giving tours of the BFF over the last two years.

“There are a lot of people that just want to know more about where their food comes from, or how food is produced,” adds Carey Gersten, a BFF steering committee member. Jackie Cramer, one of the cofounders, says, “I think a lot of people are drawn to it, especially young people, because it’s offering a vision — no, enacting a vision — of sharing and kindness, and caring.” I promise I didn’t prompt her to say that.

Big morning stretch before some February food forestry. Jonathan H. Lee

One weakness, though, is that the folks who could perhaps benefit most from the BFF aren’t taking part. The public garden sits in a remarkably diverse neighborhood — around three-quarters of residents are people of color, and over half speak languages other than English at home. During the project’s community planning process, BFF volunteers mailed out thousands of postcards in Lao, Vietnamese, Chinese, and Somali. Yet Jenna Murphy, a master’s student at Hawaii Pacific University who’s studying the BFF and the community members involved in it, reports, “Almost every person I talked to was a white, middle-class person.”

In the words of BFF cofounder Herlihy, there’s a “socioeconomic flaw” to cooperative urban farming. He described the problem to Seattle Weekly: “If you’re working two jobs and have a family, you don’t have time to volunteer at the community garden.”

So, how can we create a world where we spend less time producing and consuming — less time working at our jobs, grocery shopping, ordering new stuff online — and more time dedicated to the cool projects we create outside of the “formal economy”?

“Higher wages and shorter work weeks,” says Murphy, the grad student.

Jackie Cramer agrees. She explains that the idea for the BFF was born in 2009, at the low point of the recession, when the founding members were underemployed or unemployed, allowing them time to work on a project that’s rewarding on levels beyond the money. The BFF provides participants with something quite fundamental: free, healthful food. Imagine a world where we’re less dependent on our income to buy groceries, and have a little more time to grow our own nosh.

But we’re a long way from a world where most people could afford to work less, even if they were to get some food out of the deal. For communities to replace supermarket expenditures with free urban produce, edible gardens will have to grow and multiply and diversify — a lot. And that’s just the beginning of the political and economic changes that would be needed.

For now, the cooperative food forestry idea is at least spreading like those strawberry plants, thanks in part to the BFF’s focus on education. In addition to monthly work parties, the BFF holds classes and workshops on edible forest gardening, providing hands-on education to eager learners. “People learn how to do stuff and realize it’s pretty easy and attainable,” says Cramer. “The model of a food forest, you can actually copy it even in your backyard, as long as you understand.”

“Sharing knowledge is much more important, long term, than sharing stuff,” says Josh Farley, professor of ecological economics at the University of Vermont. “Knowledge is one of these things that no matter how much you use it, it doesn’t wear out. Stuff not only runs out, but if you make it from non-renewable resources you run out of those.” (Or, if it’s made with fossil fuels, the world burns before you run out.)

That knowledge sharing stretches far beyond the Beacon Hill community, too, as urban gardeners across the globe have learned about cultivating on public land from the BFF. “I did a tour for three people from Taiwan that have some land that they want to do a food forest in,” says volunteer Nakagawa. “They flew over here to visit the food forest, see it, and talk to some of us, so that they can start one over there.” Another group, from Mexico, exchanged growing tips — and local seeds — with volunteers. A few months ago, Resilience.org published a list of 20 urban food forests and related projects from around the world. The sharing is spreading.

The lower portion of the food forest’s two-acre “phase one.” Jackie Cramer

Not only is the BFF inspiring others to start their own food forests and teaching them how, it’s also planning to gobble up more acres of grassy Jefferson Park hillside. Initiating “phase two” means another round of community engagement, another proposal to the city, and many hours of work from a multitude of volunteers. “There’s a lot of grass out there that needs to be planted with some useful plants,” says Herlihy.

It’s probably safe to assume the BFF community will have a grand time making it happen.

This article is part of a series on the real sharing economy. Next, the series will explore how people are sharing renewable energy, and why that matters.